Policy analysis

About Public Policy and Public Problems

According to Public Policy: Politics, Analysis, and Alternatives:

Public policy is what public officials within government, and by extension, the citizens they represent, choose to do or not to do about public problems. Public problems refer to conditions the public widely perceives to be unacceptable and that therefore require intervention. These problems…can be addressed through government action; private action, where individuals or corporations take the responsibility; or a combination of the two (Kraft, 2012).”

Therefore, this page will identify public problems associated with the PennEast Pipeline Project (Project), stakeholders including citizens, government, and corporations associated with the Project, and actions to address these public problems.

Using this page, it will become evident that public problems with the Project are strongly tied and vastly intertwined with environmental and energy policy. However, before discussing environmental and energy policies directly associated with the Project, this page will narrate a history of environmental and energy policy.

The History of Environmental and Energy Policy

There are many ways to understand what the “environment” is. Simply put, different fields of study conceive of the environment differently. One field of study might strive to understand the environment as all natural things, living and non-living, another field might define the environment as biological factors and chemical interactions, and moreover, another might reduce the environment to physical exchanges of mass and energy. Of course, this list of perspectives is not exhaustive; it goes on.

Here, we will define the environment as “a set of complex systems that interact in complex ways to supply humans and other species with the necessities of life, such as breathable air, clean water, food, fiber energy, and the recycling of waste” (Kraft, 2012). This definition accurately acknowledges that society interacts with the environment, and that the environment is used for instrumental purposes.

In 1992, global leaders investigated the environment and its relationship with society. At the first international Earth Summit, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, more than 100 heads of state convened in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil to address urgent problems of environmental protection and socio-economic development. The assembled leaders signed two agreements dedicated to promoting sustainable development:

- “Convention on Climate Change“, to set an overall framework for intergovernmental effort to address challenges posed by climate change, and recognized that the climate system is a shared resource whose stability can be affected by emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

- “Convention on Biological Diversity“, to pursue the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components, and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilizing of genetic resources.

On an international stage, therefore, sustainable development emphasizes economic growth being compatible with environmental systems and social goals. It investigates “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Smith, 2012).

Moreover, on a more local stage in Northampton County, business entities such as the Sustainable Energy Fund of Allentown, Pennsylvania incorporate the values of sustainable development into their own mission statements:

Sustainable Energy Fund is a non-profit organization that assists energy users in overcoming educational and financial barriers to a sustainable energy future: a future in which energy is harvest, converted, distributed and utilized in a manner that allows all to meet their energy needs without compromising the ability of their children and grandchildren to meet their needs (Sustainable Energy Fund, 2014).”

In America, environmental and energy policies emerged uniquely in context to United States history:

Prior to the 1970s, energy policy was not a major or sustained concern of government. For the most part it consisted of federal and state regulation of goal, natural gas, and oil, particularly of the prices charged and competition in the private sector. The goal was to stabilize markets and ensure both profits and continuing energy supplies” (Kraft, 2012).

Responding to industrialization of the late 19th century, American citizens of the 1960s participated in environmental movements. At this time, postindustrial social values pervaded concurrently with the growth of economic development and consumerism following World War II (Kraft, 2012).

Citizens’ sentiments about environmental and energy policy motivated public officials to enact new laws. In 1963, the Clean Air Act was designed to control air pollution, encouraging breathable air. In 1972, the Clean Water Act was put into effect to govern water pollution. Likewise, the Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974 ensured water quality standards at the federal level. And in 1976, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act was enacted to manage the disposal of solid and hazardous waste.

American public officials constructed national environmental public policies with multiple purposes in mind. They were motivated to prevent negative economic externalities from pollution, act ethically with the right decisions, and meet public demand for political reelection. Their policies help guarantee citizens with necessary resources like air, water, and waste disposal in American society (Kraft, 2012).

Yet, American public officials came under forceful criticism from business groups, conservatives and economists worrying about the costs policies imposed on society (Kraft, 2012). In constructing American environmental and energy policies, mixed intentions, goals and expectations impact future plans, programs, and decisions in America. Environmental and energy policies in America continue to be contested for a number of reasons:

Public policy is not made in a vacuum. It is affected by social and economic conditions, prevailing political values and the public mood at any given time, the structure of government, and national and local cultural norms, among other variables. Taken together, this environment determines which problems rise to prominence, which policy alternatives receive serious consideration, and which actions are viewed as economically and politically feasible…Presented with conflicting assumption and interpretations, [citizens] need to be aware of the sources of information and judge for themselves which argument is the strongest” (Kraft, 2012).

Stakeholders in the Project

Now, more than ever, it is critical for [stakeholders] to understand how the FERC process works and learn best practices to protect their rights … When a pipeline cuts through a community, it impacts different constituencies in different ways. Each affected stakeholder … represents a unique interest, and plays a unique role in the process.” – Law Offices of Carolyn Elefant

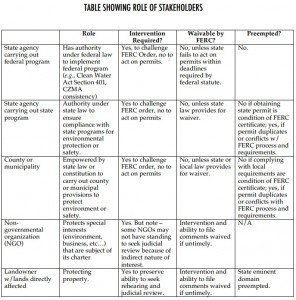

Largely, 5 stakeholders comprise the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) pipeline certification process of an interstate gas pipeline:

- “State agency carrying out the federal program”, which has the authority under federal law to implement the federal program (e.g. Clean Water Act Section 401, Costal Zone Management Act consistency).

- “State agency carrying out the state program”, which has authority under state law to ensure compliance with state programs for environmental protection or safety.

- “Counties or municipalities”, which are empowered by state law or constitution to carry out county or municipal provisions to protect the environment or safety.

- “Non-governmental organizations”, which protect special interests (i.e. the environment, businesses, etc…) that are subject of its charter.

- “Landowners with lands directly affected”, who want to protect their property.

One can better understand stakeholders and their roles with respect to intervention, waivable rights by FERC, and preemption, respectively per stakeholder. So, what is intervention, waiver, and preemption?

- “Intervention” is an official right of an intervenor. Intervenors receive the pipeline company’s application filings and other FERC documents related to the case and materials filed by other interested parties. Intervenors are able to file briefs, appear at hearings and be heard by the courts if they choose to appeal FERC’s final ruling. However, along with these rights come responsibilities. Intervenors are obligated to mail copies of what they file with FERC to all the other parties at the time of filing. In major cases, there may be hundreds of parties.

- “Waiver” refers to legal waivers. Waivers are legal documents releasing some requirement, giving up some right, or agreeing to hold some entity blameless.

- “Preemption” refers to the result when federal law supersedes or overrides state laws or rules governing the same object due to the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution. “Field preemption” refers to when state law and federal law conflict, and when federal law displaces state law entirely irrespective of any actual conflict. “Conflict preemption” refers to when federal and state authorities share regulatory authority, and when state law must give way. Federal authorities – both FERC and the Department of Transportation – together regulate the field of pipeline safety and displace state regulation.

The following table, which was provided in a document by the Law Offices of Carolyn Elefant, elaborates on intervention, waivers and preemption as they relate to the 5 types of stakeholders involved in a FERC pipeline certification process.

According to the document, even though the federal Natural Gas Act (NGA) preempts much of state and local pipeline regulation, preempted stakeholders are not powerless. Stakeholders can intervene in, and participate in the FERC process on issues related to routing, making environmental recommendations and preparing and submitting studies on impacts that may be relevant to FERC’s public interest findings. However, FERC is an executive agency, not a legislative body. As such, it is not influenced by letters and petitions in mass urging rejection of pipe.

Stakeholders that intervene in the FERC process can seek rehearing of FERC’s certificate and challenge it on judicial review. Thus, stakeholders should intervene in the FERC process to protect their interests and preserve the right to comment and challenge a decision.

Though early maps may suggest that a pipeline route will not cross one’s land, landowners in close vicinity of the route should intervene because pipeline routes change frequently during the certification process for various reasons, such as minimizing impacts to environmentally sensitive areas or residential structure. Thus, landowners in close vicinity of the route could see a pipeline re-routed through their property. Only if landowners intervene in a timely manner will they have the ability to challenge a new route configuration.

More Information for Landowners and about Intervention

In an interview with StateImpact Pennsylvania via NPR, Carolyn Elefant, a Washington DC-based attorney who has defended landowners involved in pipeline process, provide the following advice:

- Landowners should retain an attorney if they expect the pipeline will directly affect a part of their property.

- Landowners should always use an attorney if approached by a pipeline company with an easement.

- All citizens should comply with the rules when communicating with FERC to best have their voice be heard.

- For all citizens, participating is the best way not to be ignored during the process.

Elefant stated that citizens who are impacted by a pipeline should intervene. In this document, under “Part IV: Practical Tips”, then under section “C. Sample Intervention”, the Law Offices of Carolyn Elefant provide a sample form motion to intervene for landowners, private citizens, municipalities, and non-governmental organizations. In addition, FERC explains how to file an intervener status. Moreover, FERC explains the rights and responsibilities of intervention in this document.

More Information about the Interests and Role of FERC

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission is an independent, Federal agency that regulates the interstate transmission of electricity, natural gas, and oil. FERC also reviews proposals to build liquified natural gas terminals and interstate natural gas pipelines. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 gave FERC additional responsibilities. Since 2005, FERC approves the siting and abandonment of interstate natural gas pipelines and storage facilities (Mark Gallagher, Princeton Hydro).

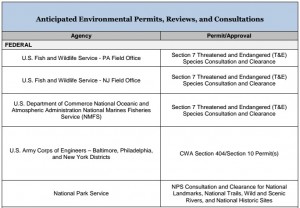

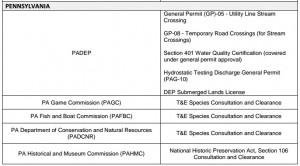

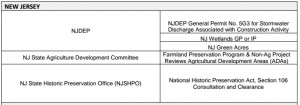

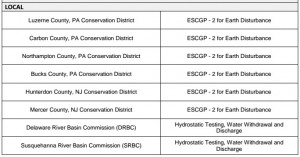

FERC would approve the Project in accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). FERC requires PennEast to obtain various permits, reviews, and consultations at federal, state, and local levels. To view anticipated environmental permits, reviews and consultations, please see Exhibit C or view images of Exhibit C below. In addition, see “About Project Policies”, which is located on this page below, for elaboration on selected policies.

More Information about the Interests and Role of PennEast

The General Project Description of a PennEast Resource Report indicates the following public problem:

The lack of a new pipeline with access to sources in Pennsylvania will continue to create dramatic seasonal price fluctuations in Pennsylvania and New Jersey with higher gas and electric rates and an increased potential for energy shortages during peak demand, resulting in threats to business continuity, public safety, and national security.”

According to a announcement from PennEast,natural gas prices in New Jersey traded as high as $100 per dekatherm this past winter. Natural gas in the area that PennEast will access traded in the range of $3 to $4 per dekatherm. The proposed pipeline will help reduce this price volatility to the benefit of New Jersey’s nearly 3 million gas consumers. Still, PennEast reports:

The Project will provide additional opportunities to buy and sell supplies and to transport natural gas to where it is needed and valued most.”

According to our research, the problem stated by PennEast, which is closely tied to economic growth, must also consider environmental health and societal acceptability to rise to prominence and be compatible with environmental systems and social goals.

About Project Policies

On November 20, 2014 at the Nurture Nature Center of Easton, Pennsylvania, Mark Gallagher of Princeton Hydro said the following were key federal regulations applicable to the PennEast Pipeline:

- The Natural Gas Act

- The National Environmental Policy Act

- The Endangered Species Act

- The Wild and Scenic River Act

- The National Historic Preservation Act

- The Clean Water Act Section 404 Wetlands

- The Clean Water Act Section 401 Water Quality Certifications

- The Clean Water Act Section 303 Water Quality Standards

“Natural Gas Act“ enacts direct federal regulation of the natural gas industry. Under NGA, FERC is responsible for setting just and reasonable rates for the transmission or sale of natural gas in interstate commerce. Also under NGA, FERC grants certificates allowing construction and operation of facilities used in interstate gas transmission and authorizing the provision of service. Moreover, FERC must issue a “Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity” to permit pipeline companies to charge customers for some of the expense incurred in pipeline construction and operation. Under NGA, FERC must approve the abandonment of any pipeline facility or service.

“National Environmental Policy Act” states federal agencies shall to the fullest extent possible interpret and administer the policies, regulations, and public laws of the United States in accordance with the policies set forth in NEPA and in these regulations. In addition, federal agencies shall to the fullest extent possible assess the reasonable alternatives to proposed actions that will avoid or minimize adverse effects of these actions upon the quality of the human environment. Thus, FERC must consider project alternatives, as well as a wide range of potential impacts, including socio-economic and cumulative impacts. Cumulative impacts result from the proposed action as well as past, present and foreseeable actions, which may be minor individually but collectively, are significant.

“Endangered Species Act” protects endangered and threatened species and their habitats, and recovers imperiled species and the ecosystems upon which they depend so they no longer need protection under the Act. Section 7 of the Act requires Federal agencies to use their legal authorities to promote the conservation purposes of the Act and to consult with Fish & Wildlife Services (FWS) and National Marine Fisheries Services (NMFS), as appropriate, to ensure that effects of actions they authorize, fund or carry out are not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of listed species. FWS or NMFS can offer reasonable and prudent alternatives about how the proposed action could be modified to avoid jeopardy.

“Wild and Scenic River Act” was constructed to preserve certain rivers with outstanding natural, cultural, and recreational values. Because protection of the river is provided through voluntary stewardship by landowners and river users and through regulation and programs of federal, state, local or tribal government, the Act encourages river management that crosses political boundaries and promotes public participation in developing goals for river protection. Each river is administered by either a federal or state agency, and designated segments need not include the entire river and may include tributaries. The Act limits how much land the federal government is allowed to acquire from willing sellers.

“National Historic Preservation Act” declares that the historical and cultural foundations of the United States should be preserved as a living part of our community life and development in order to give a sense of orientation to the American people. In 1966, the Act acknowledged, in the face of ever-increasing extensions of urban centers, highways, and residential, commercial, and industrial developments, the government and non-governmental historical preservation programs were inadequate to insure future generations a genuine opportunity to appreciate and enjoy the rich heritage of the United States. Thus, the Act advocates increased knowledge of our historic resources, the establishment of better means of identifying and administering them, and the encouragement of their preservation to improve the planning and executing of Federal and federally assisted projects, and to assist economic growth and development.

“Clean Water Act” regulates pollutants: priority pollutants including various toxic pollutants, conventional pollutants that are amenable to treatment by a municipal sewage treatment plant, and non-conventional pollutants that are not identified as either conventional or priority. “Section 404” states the Secretary may issue permits, after notice and opportunity for public hearing, for the discharge of dredged or fill material into navigable waters at specified disposal sites. “Section 401” states that any applicant for Federal license or permit must provide, for any activity that may result in any discharge into navigable waters, a certification from the State in which the discharge originates or will originate or if appropriate, from the interstate water pollution control agency having jurisdiction over the navigable waters. “Section 303” details various Water Quality Standards and Implementation Plans that could have material effects on the Project.

Next

Next is the Technical Analysis.