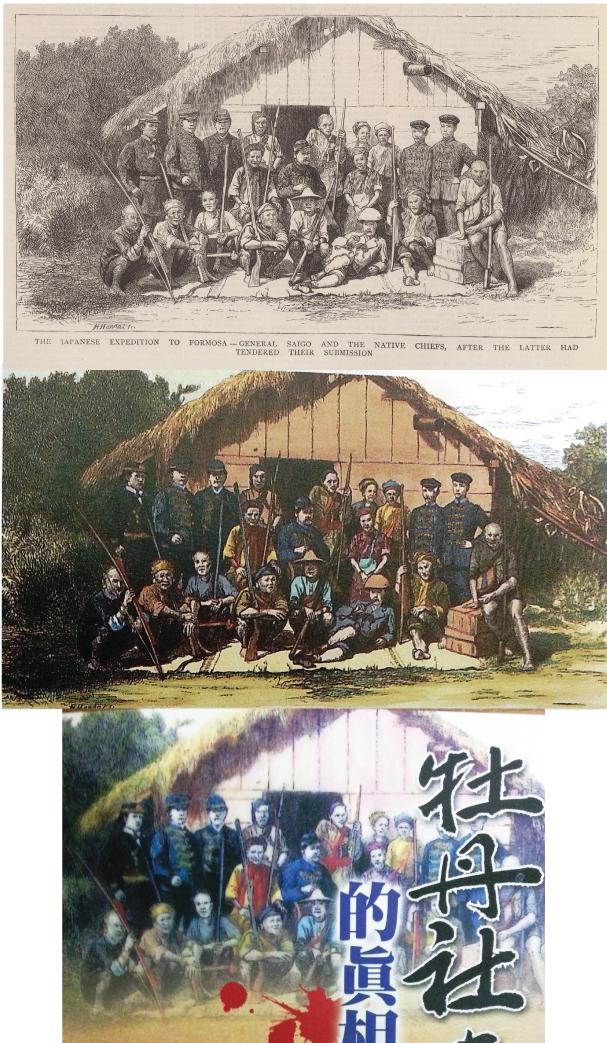

During the period of Japanese colonial rule in Taiwan (1895-1945), thousands of photographs reached mass audiences via picture postcards. Seventy years later, many of these same images have enjoyed a revival, even though the empire has long since vanished. In this essay, I trace the history of one particular photograph: a group portrait of Saigo Judo (Tsugumichi), a handful of Japanese comrades, and his Paiwan allies in the Hengchun peninsula. This is one of the few surviving photographs of the Japanese military expedition to Taiwan in 1874. I begin with two fairly recent Taiwanese book covers that utilize an 1874 photograph that formed the basis for a widely disseminated 1908 postcard:

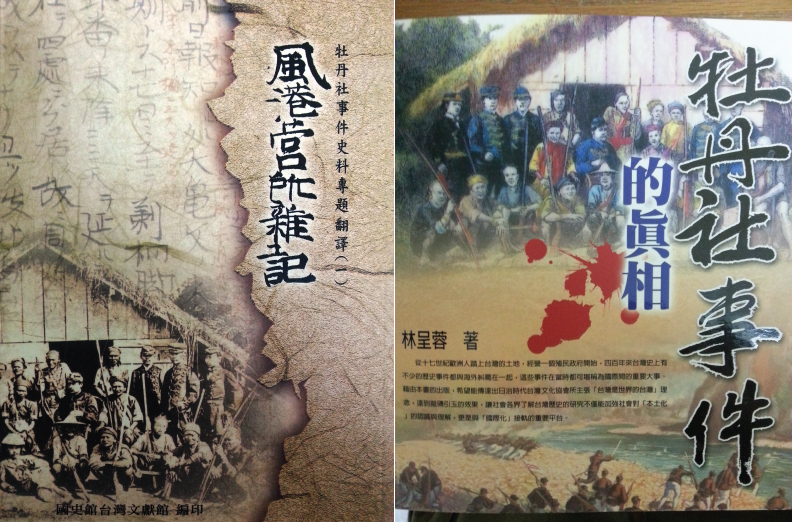

The title on the left, 風 港營所雜記: 牡丹社事件史料専頭翻譯 (Miscellany from Fenggang Camp: A Specialist Edition of Translated Historical Materials on the Mudan Incident) [1], is about as technical and narrowly targeted as a book can be. Except for the cover, there are no illustrations in this book, which was published by the Taiwan National Archives (Taiwan Historica) in 2003. To the right is a very different kind of publication: a colorful picture-packed general-audience book titled 牡丹社事件的真相 (The Truth about the Mudan Incident).[2]

The title on the left, 風 港營所雜記: 牡丹社事件史料専頭翻譯 (Miscellany from Fenggang Camp: A Specialist Edition of Translated Historical Materials on the Mudan Incident) [1], is about as technical and narrowly targeted as a book can be. Except for the cover, there are no illustrations in this book, which was published by the Taiwan National Archives (Taiwan Historica) in 2003. To the right is a very different kind of publication: a colorful picture-packed general-audience book titled 牡丹社事件的真相 (The Truth about the Mudan Incident).[2]

At first glance, it is easy to miss the resemblance between the two cover illustrations. One is a black-and-white photograph, and the other is a color drawing. Moreover, they are reverse images of each other. We can see from the cropped versions below, however, that the same scene is being quoted on both covers:

But which reproduction is “backwards”? Was Saigo Tsugumichi, the seated man in the center (circled in red) with the cap, looking to the right (from the cameraman’s perspective), or was he looking towards the left? I’m not sure. It seems that there are two lines of descent–from an 1874 photo and an 1875 etching–that have produced two separate genealogies of serial reproduction, both originating from a glass-plate negative that appears lost to the ravages of time.

But which reproduction is “backwards”? Was Saigo Tsugumichi, the seated man in the center (circled in red) with the cap, looking to the right (from the cameraman’s perspective), or was he looking towards the left? I’m not sure. It seems that there are two lines of descent–from an 1874 photo and an 1875 etching–that have produced two separate genealogies of serial reproduction, both originating from a glass-plate negative that appears lost to the ravages of time.

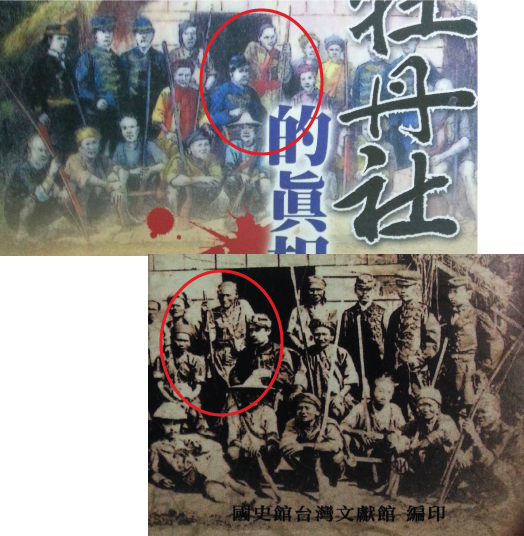

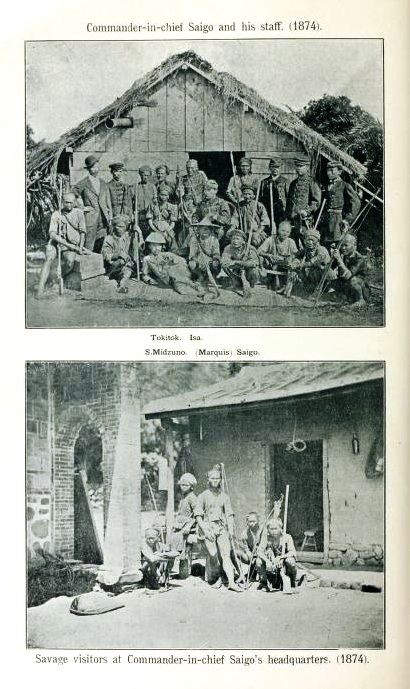

This image was created in late 1874–Professor Yamamoto Yoshimi has proposed a window of November 27-28. Yamamoto’s estimate is consistent with a tradition established in 1936 by the photograph’s custodians, and is bolstered by an extensive reading of a wide variety of supporting contemporary documents and secondary scholarship. [3] This window will be accepted as a starting point for this post. This group portrait records a conference, ceremony or photo-op that included commander Saigo Tsugumichi, a Chinese-language specialist name Mizuno Jun, representatives of some of the “18 Tribes of Langqiao,” and various other participants in the meeting. The portrait was created at the end of a six-month punitive expedition undertaken by Japanese soldiers to the Hengchun (also known as Langqiao) peninsula in southern Taiwan. It will be referred to in the post as the “group portrait.” This conflict between nationally dispatched Japanese troops and locally organized groups of Taiwanese is known in Japan as the “Taiwan Expedition” 台湾出兵 or “Punitive Troop Dispatch to Taiwan” 征台の役 and in Taiwan as the “Mudan Incident” 牡丹社事件. In this post, it will be referred to as the Taiwan Expedition or the 1874 Expedition.

In very broad strokes, the Taiwan Expedition saw about 3600 Japanese troops and supporters sent to the island to punish Taiwanese residents of Mudan (also called “Botan”) for killing 54 shipwrecked Ryukyuan Islanders from Miyakojima in 1871.

In Japan and Taiwan, the time and location of these events are widely known, if not the details of the complex and drawn out diplomacy, logistics, and local repercussions that attended them. The Expedition is considered by some to be Japan’s first attempt to colonize Taiwan; others have analyzed its significance as modern Japan’s first foreign war; and yet others have regarded events of 1871 through 1874 as a critical juncture in Sino-Japanese diplomatic history (these interpretations are not mutually exclusive). Thus, the photo used on the covers of these two recent books are easily recognizable in Japan and Taiwan.

In Japan and Taiwan, the time and location of these events are widely known, if not the details of the complex and drawn out diplomacy, logistics, and local repercussions that attended them. The Expedition is considered by some to be Japan’s first attempt to colonize Taiwan; others have analyzed its significance as modern Japan’s first foreign war; and yet others have regarded events of 1871 through 1874 as a critical juncture in Sino-Japanese diplomatic history (these interpretations are not mutually exclusive). Thus, the photo used on the covers of these two recent books are easily recognizable in Japan and Taiwan.

Nonetheless, as Yamamoto indicates in her article, and as Professor Douglas Fix has pointed out in a recent conference paper [4], we lack extant evidence to definitively identify the photographer and most of the figures in the picture. Professor Robert Eskildsen, another historian with extensive knowledge about Taiwan-Japanese relations during this period [5], has searched for the original source of this image in repositories throughout Taiwan and Japan, and has come up empty. So despite the group portrait’s notoriety, its origins and even contents remain somewhat murky.

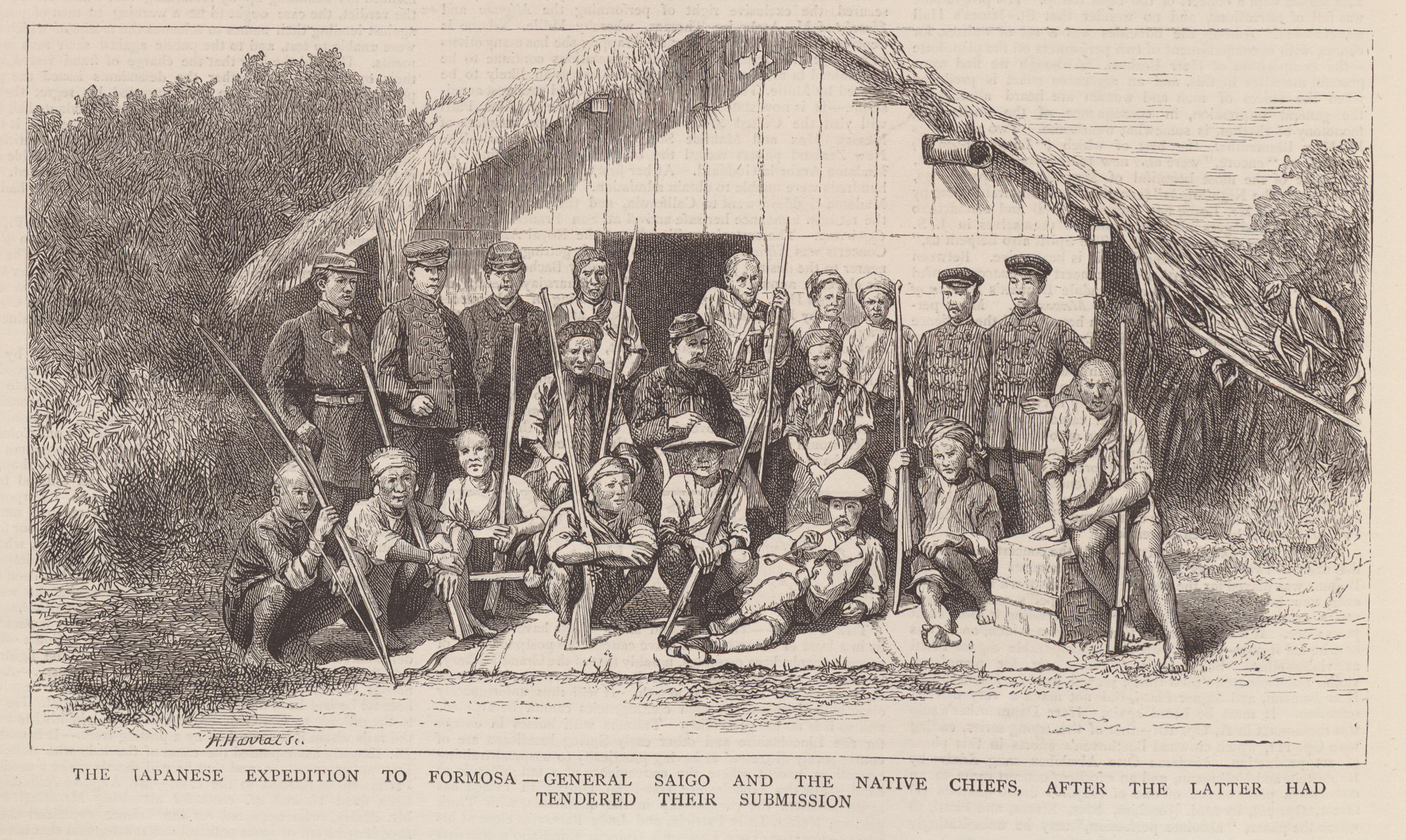

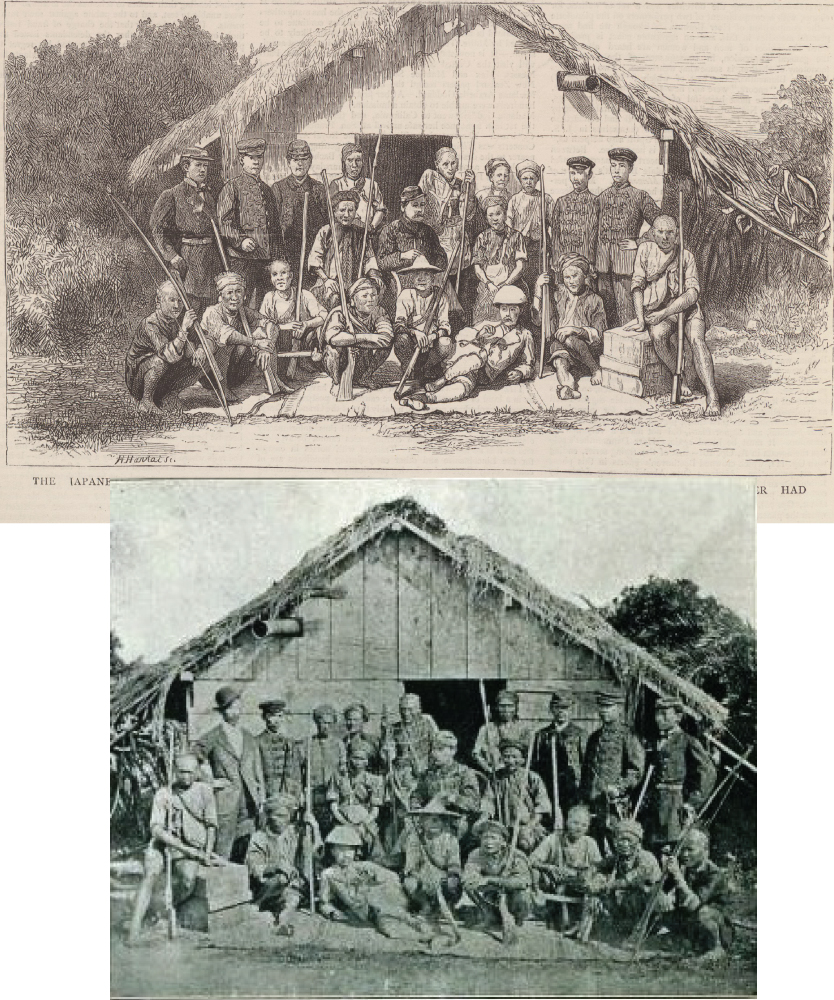

The image that was likely created in November 1874 was reproduced soon after in February 1875 as an etching in The Graphic: An Illustrated Weekly Newspaper. This is the first publicly disseminated version of the group portrait that I am aware of:

Image from: Formosa: Nineteenth Century Images, Reed College “The Japanese Expedition to Formosa–General Saigo and the Native Chiefs, after the Latter had Tendered their Submission.” The Graphic: An Illustrated Weekly Newspaper Vol XI, No. 274 (27 February 1875): 204.

Image from: Formosa: Nineteenth Century Images, Reed College “The Japanese Expedition to Formosa–General Saigo and the Native Chiefs, after the Latter had Tendered their Submission.” The Graphic: An Illustrated Weekly Newspaper Vol XI, No. 274 (27 February 1875): 204.

In the 1870s, it was not yet possible to publish photographs in newspapers, tabloids, or magazines without driving the price of such publications out of reach. Instead, etchings like the one above were modeled on photographic images so that the images could be published in mass-circulation formats. We can think of this process as “reformatting,” but as we shall see, the process involved a great deal more than a change of medium.

The first published copy of the photograph version of this image, (that I know of), appeared in James Davidson’s The Island of Formosa, Past and Present (London: Macmillan, 1903). The quarter-century time-lag between the two appearances can be partly attributed to the technological requirements of mass producing photographs in commercial books and magazines (as opposed to limited edition albums and government reports). Davidson’s book appeared at about the same time the National Geographic Magazine published its first set of photographs in 1904. Thus, we can regard Davidson’s use of reproduced photographs as fairly “cutting edge” for a mass-circulation book.

James Wheeler Davidson, The Island of Formosa, Past and Present. History, People, Resources, and Commercial Prospects. Tea, Camphor, Sugar, Gold, Coal, Sulphur, Economical Plants, and Other Productions (London and New York: Macmillan & Co.; Yokohama: Kelly and Walsh, 1903), pp. 126-127. link to book

James Wheeler Davidson, The Island of Formosa, Past and Present. History, People, Resources, and Commercial Prospects. Tea, Camphor, Sugar, Gold, Coal, Sulphur, Economical Plants, and Other Productions (London and New York: Macmillan & Co.; Yokohama: Kelly and Walsh, 1903), pp. 126-127. link to book

As we can see, Davidson’s version is a reverse image of the one published twenty-eight years earlier in The Graphic:

Davidson’s book was first published in Yokohama, and provided Western readers with a positive account of Japanese colonial rule’s first seven years in Taiwan. Davidson was on familiar terms with Japan’s top politicians and military men. In his preface, Davidson thanked “the late Marquis Saigo” for “two valuable old photographs,” which I take to be the photographs inserted between pages 126 and 127 of his book (shown above). Since Saigo Tsugumichi, the commander of the expedition, died in 1902, while Davidson was working on his book (from 1895-1903), I assume that Saigo himself provided Davidson a copy of this photograph.

Davidson’s book was first published in Yokohama, and provided Western readers with a positive account of Japanese colonial rule’s first seven years in Taiwan. Davidson was on familiar terms with Japan’s top politicians and military men. In his preface, Davidson thanked “the late Marquis Saigo” for “two valuable old photographs,” which I take to be the photographs inserted between pages 126 and 127 of his book (shown above). Since Saigo Tsugumichi, the commander of the expedition, died in 1902, while Davidson was working on his book (from 1895-1903), I assume that Saigo himself provided Davidson a copy of this photograph.

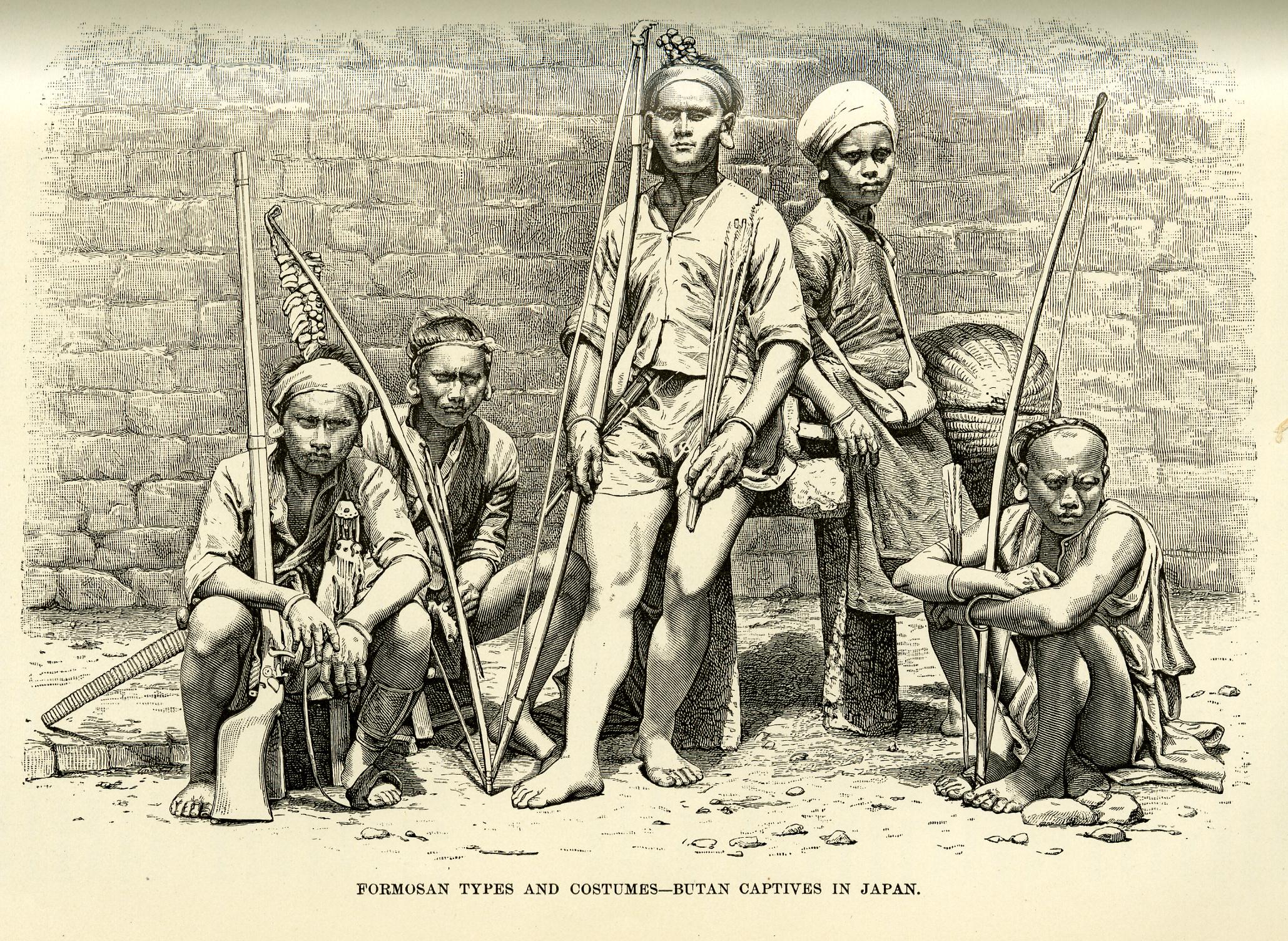

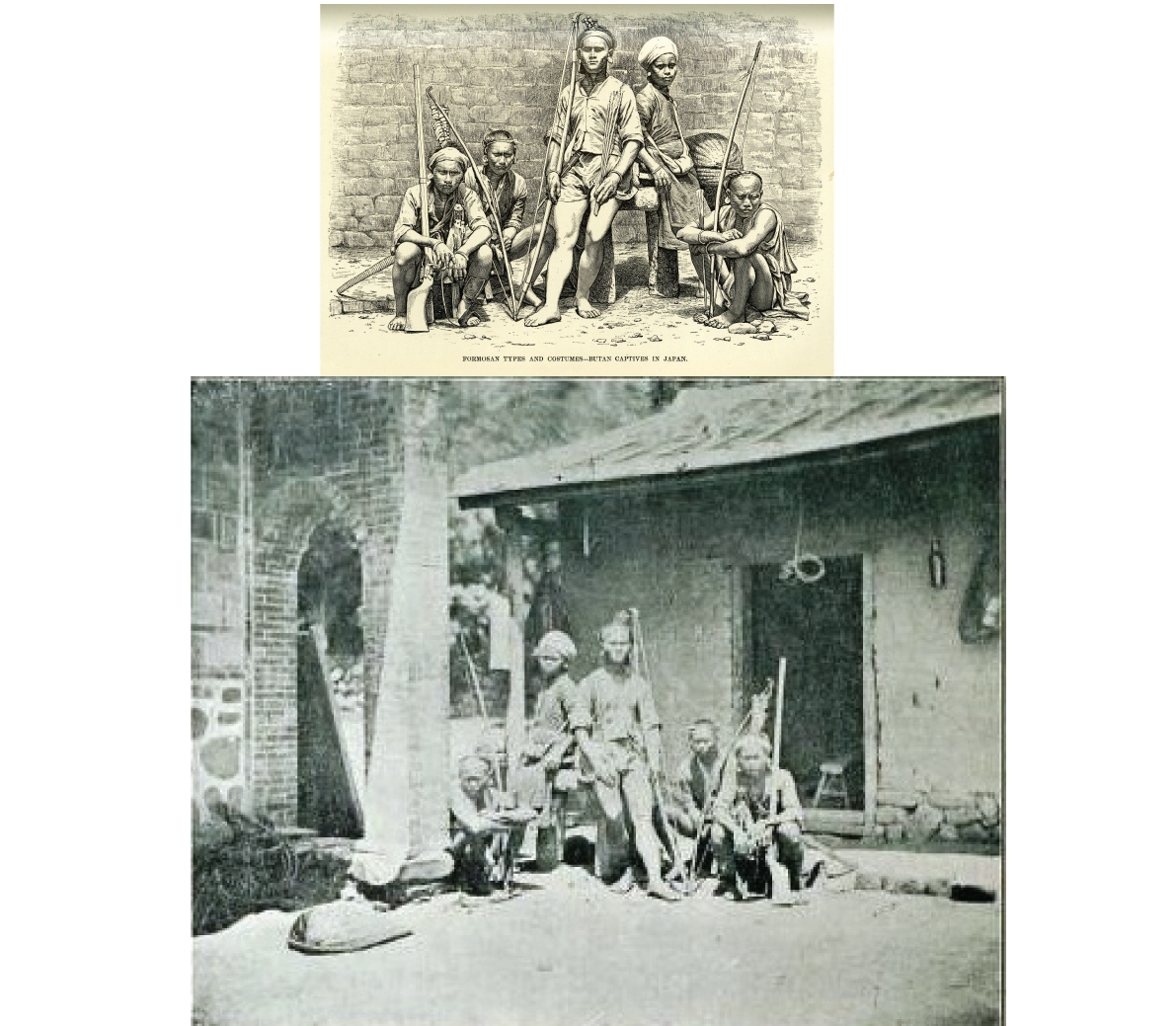

One is tempted to think that since Saigo himself gave the photo to Davidson, his image is “correct,” while the artist who etched the figure for the The Graphic, (Horace Harral), reversed the image, or worked from a reversed print. However, a similar reversal occurred with the other “Taiwan Expedition” photograph in Davidson’s book, which he titled “Savage Visitors at Commander-in-Chief Saigo’s Headquarters” (see above). A decade before Davidson’s book was published, the etching below (by A. Kohl) appeared in a famous encyclopedic study of the world’s peoples by the anarchist geographer Elisée Reclus:

Image from: Formosa: Nineteenth Century Images, Reed College “Formosan types and costumes – Butan captives in Japan,” in Elisée Reclus, Formosa, The earth and its inhabitants. Asia. Vol. II, East Asia: Chinese empire, Corea, and Japan, edited by A. H. Keane (New York: D. Appleton, 1884), p. 280. link to book

Image from: Formosa: Nineteenth Century Images, Reed College “Formosan types and costumes – Butan captives in Japan,” in Elisée Reclus, Formosa, The earth and its inhabitants. Asia. Vol. II, East Asia: Chinese empire, Corea, and Japan, edited by A. H. Keane (New York: D. Appleton, 1884), p. 280. link to book

Kohl’s etching, like Harral’s, is a reverse image of a photograph from Davidson’s book (with a number of architectural features cropped out):

Is this a coincidence? Did two different artists, separated widely in time and space, happen to reverse the images provided to them in photographs from the “Taiwan Expedition”? It may be the case that they “traced” the photo to achieve scale and proportion, and that the presses merely transferred the reformatted images (etchings) to plates, and that the images was reversed during the printing process. Or the image might have been reversed in a transfer from negative to print in the photos that were distributed to Davidson and later publishers. In any event, after some kind of late nineteenth-century fork in the road, etchings and drawings reproduced Harral’s perspective, while photographs reproduced Davidson’s. Until an actual glass-plate negative of this photo is unearthed, we cannot be sure which way Saigo and the Langqiao headmen were facing on that November day in 1874.

Is this a coincidence? Did two different artists, separated widely in time and space, happen to reverse the images provided to them in photographs from the “Taiwan Expedition”? It may be the case that they “traced” the photo to achieve scale and proportion, and that the presses merely transferred the reformatted images (etchings) to plates, and that the images was reversed during the printing process. Or the image might have been reversed in a transfer from negative to print in the photos that were distributed to Davidson and later publishers. In any event, after some kind of late nineteenth-century fork in the road, etchings and drawings reproduced Harral’s perspective, while photographs reproduced Davidson’s. Until an actual glass-plate negative of this photo is unearthed, we cannot be sure which way Saigo and the Langqiao headmen were facing on that November day in 1874.

At least two recent Taiwanese publications have reproduced the group portrait, and based their art on the etching, and not the photograph. We can make this claim because Horace Harral changed the hat and clothing on one of the figures in the photograph version of the portrait. I’ve used a better print than Davidson’s to highlight this alteration, and I’ve digitally reversed the Harral etching for purposes of comparison. The point here is that in the photograph, the man standing behind the seated musket-toting Langqiao warrior is wearing a cocked derby hat and a slightly rumpled suit jacket, while that same person in Harral’s etching looks like a well-scrubbed cadet or prep-school student. See the figures in red boxes:

I am not sure why Harral modified the attire of the man standing with one hand on his hip. Whatever the reasons, his alteration has survived in reproductions based on Harral’s sketch. Fast forwarding to a 1998 Taiwanese publication about Indigenous textiles, we see an example of an author who referred back to Harral’s etching to illustrate a contemporary text:

I am not sure why Harral modified the attire of the man standing with one hand on his hip. Whatever the reasons, his alteration has survived in reproductions based on Harral’s sketch. Fast forwarding to a 1998 Taiwanese publication about Indigenous textiles, we see an example of an author who referred back to Harral’s etching to illustrate a contemporary text:

From: Li Shali 李莎莉, Taiwan yuan zhu min yi shi wen hua 台灣原住民衣飾文 Culture of clothing among Taiwan aborigines : tradition, meaning, images (Taibei: Nantian shuju, 1998), p. 63

From: Li Shali 李莎莉, Taiwan yuan zhu min yi shi wen hua 台灣原住民衣飾文 Culture of clothing among Taiwan aborigines : tradition, meaning, images (Taibei: Nantian shuju, 1998), p. 63

Although the author attributes this image to the Illustrated London News “ca. 1880,” I cannot find such an image in that publication, and think that the The Graphic illustration is indeed the source. Notice that the image is a reverse image of the Davidson photo of the same scene, and that the man standing with his hand on his hip is wearing a smart uniform and cap, and not a cocked derby and suit jacket. The image in Li’s book has been colorized, presumably to highlight the textile types from the period. Li employed this image to illustrate the use of Plains Aborigine betel nut bags. The colors added to the drawing make it easy to locate the bag. There is no reason to believe, however, that independent illustrators would arrive at the same color scheme for this black and white etching, since we have no supporting evidence to give us an idea of the actual colors of the clothing worn by most of the sitters in 1874. That these colors, along with the altered hat and jacket turn up again in yet another reproduction suggests a game of visual “telephone,” wherein each successive publisher transmits the alternations of a previous one as the image drifts further and further away from its original likeness. Based on the foregoing evidence, I believe that the middle image (from Li Shali’s book) is a copy from the top image (Harral’s etching), and that the bottom image (from the 2006 book cover) is derived from the middle image (Li Shali’s book).

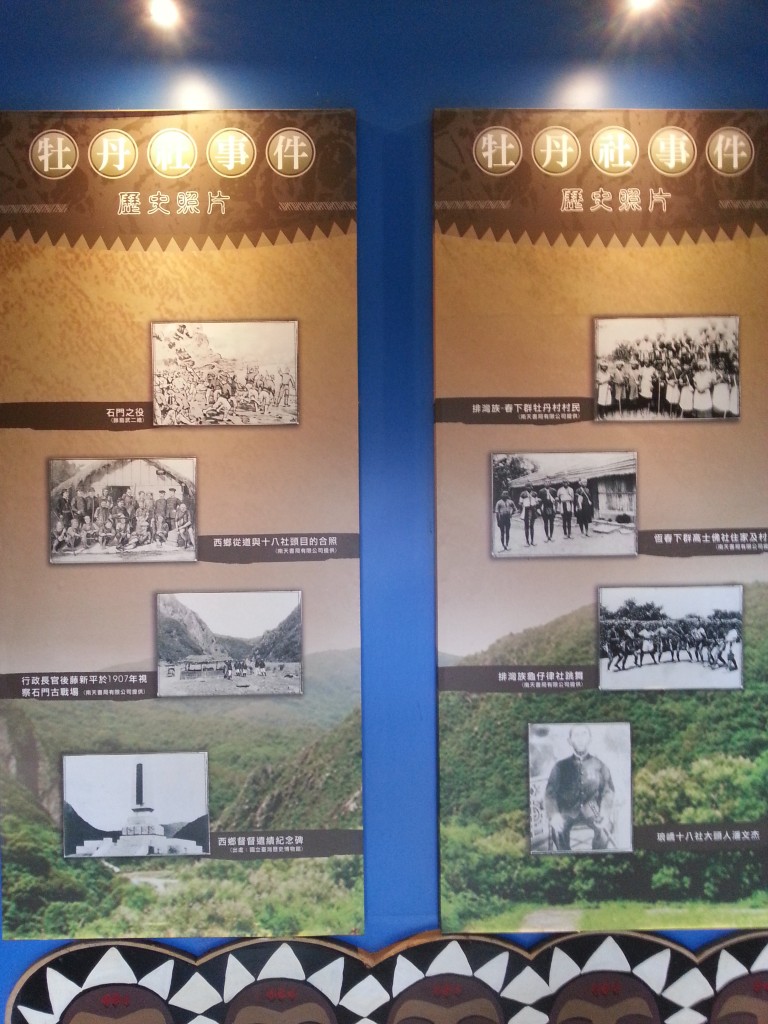

Of course, it is important to ask what the various artists, authors, photographers, and sitters (models) intended to convey by producing, reproducing, and disseminating this portrait. At this point, I have only tried to establish a simple, but often overlooked point: the manipulation of photographic images–through cropping, alterations, coloration, labeling, and other means–is a normal part of the publication and dissemination process. We have already seen how one very famous image took on parallel lives as an etching and photograph because at some fork in the road, probably in the late nineteenth century, a reversal of the image occurred during the reproduction process. Moreover, very early in the transmission process, an influential artist, Horace Harral, created a fictitious character to replace a sitter. Subsequent publications have retained this presumably fictitious character as part of the portrait. Even the tourist station at the actual site of the battle, in Mudan Township, has adopted this altered photo in its otherwise scrupulous and very carefully arranged historical exhibit:

Photographs by author, December 5th, 2014.

Photographs by author, December 5th, 2014.

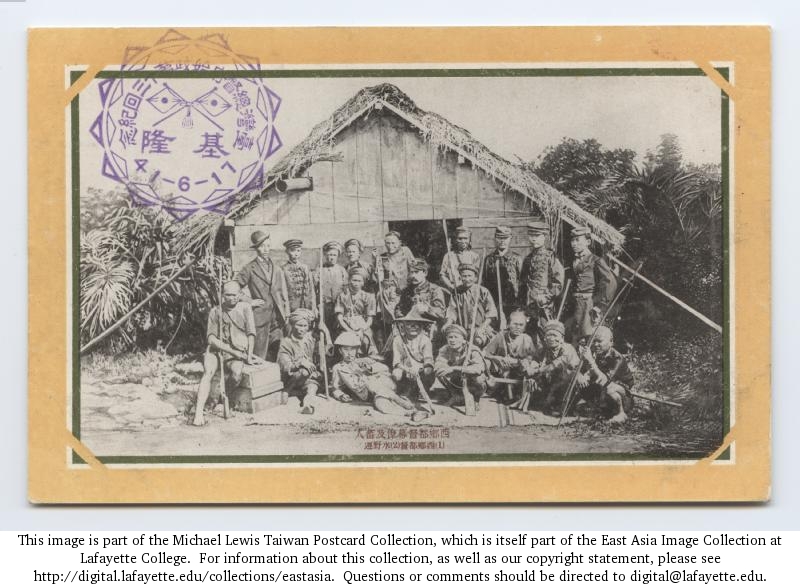

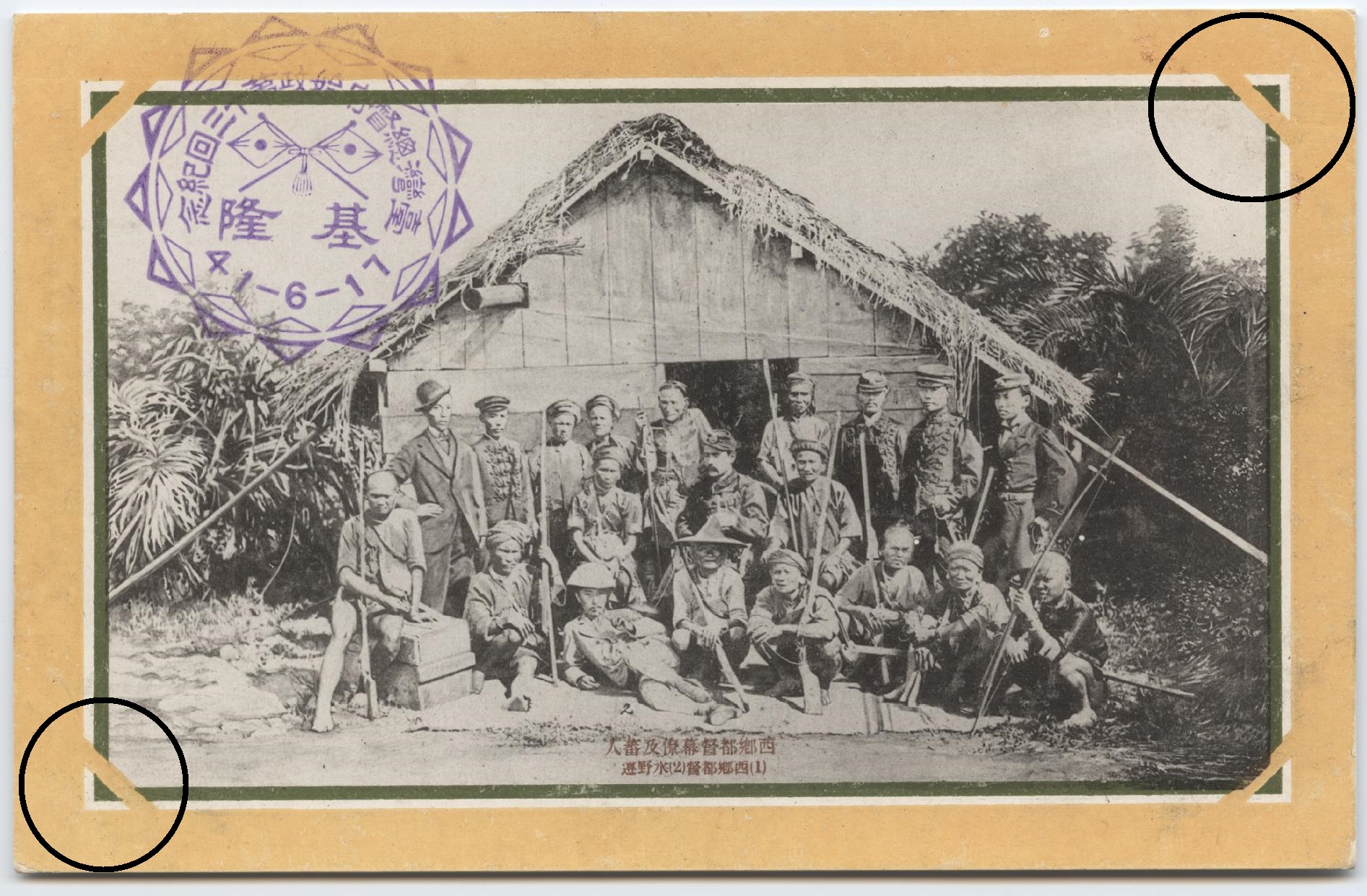

The majority of reproductions of the group portrait are based on the photograph. Unsurprisingly, alternations still abound. Five years after Davidson’s book emerged, the Government General of Taiwan published the group portrait as part of a two postcard set to commemorate the 13th Anniversary of Japanese rule in the colony. It was issued on June 17th, 1908.

[lw0242] [Saigo Tsugumichi and Mizuno Jun in Hengchun, 1874]

[lw0242] [Saigo Tsugumichi and Mizuno Jun in Hengchun, 1874]

The most striking difference between the Davidson reproduction and the postcard is that the latter includes more foliage on either side of the portrait. The Government General print confirms that Harral did not pencil in vegetation to make the scene more rustic, or tropical, but rather that Davidson’s reproduction cropped out vegetation on each side of the main scene. The captioning has also changed. Davidson captioned the group portrait in two ways. On top, “Commander-in-Chief Saigo and his staff (1874)” is written, and below are the names “Tokitok, Isa, (Marquis) Saigo, S. Midzuno [Mizuno].” In contrast, the Taiwan Government General postcard only names Saigo Tsugumichi and Mizuno Jun. By 1908, Mizuno had served as the Government General’s first Civil Administrator (1895-1897). Mizuno served under Governors-General Kabayama Sukenori (who also participated in the 1874 Expedition), Taro Katsura and Nogi Maresuke. Since the occasion of the card was to commemorate the Government General, it made sense to highlight Mizuno’s presence in Hengchun.

“Tokitok” (or Tauketok) was a paramount headman for all eighteen of lower Hengchun’s loosely confederated “tribes” during the late 1860s and early 1870s. Isa was another important headman in Langqiao. However, Tokitok died in 1873, and did not have any dealings with Japanese emissaries. He could not have been in this portrait. Tokitok was well known to U.S. Consul to Amoy, and later advisor to the Japanese government, Charles W. Le Gendre. Davidson himself relied heavily on Le Gendre, and the American journalist Edward House, for his section about the 1874 Expedition. Based on the repeated references to Tokitok and Isa in these documents, I think that Davidson himself must have inferred that Tokitok and Isa were present in the group photograph. Like Harral’s alteration, Davidson’s innovation was picked up and transmitted by later publishers (see below).

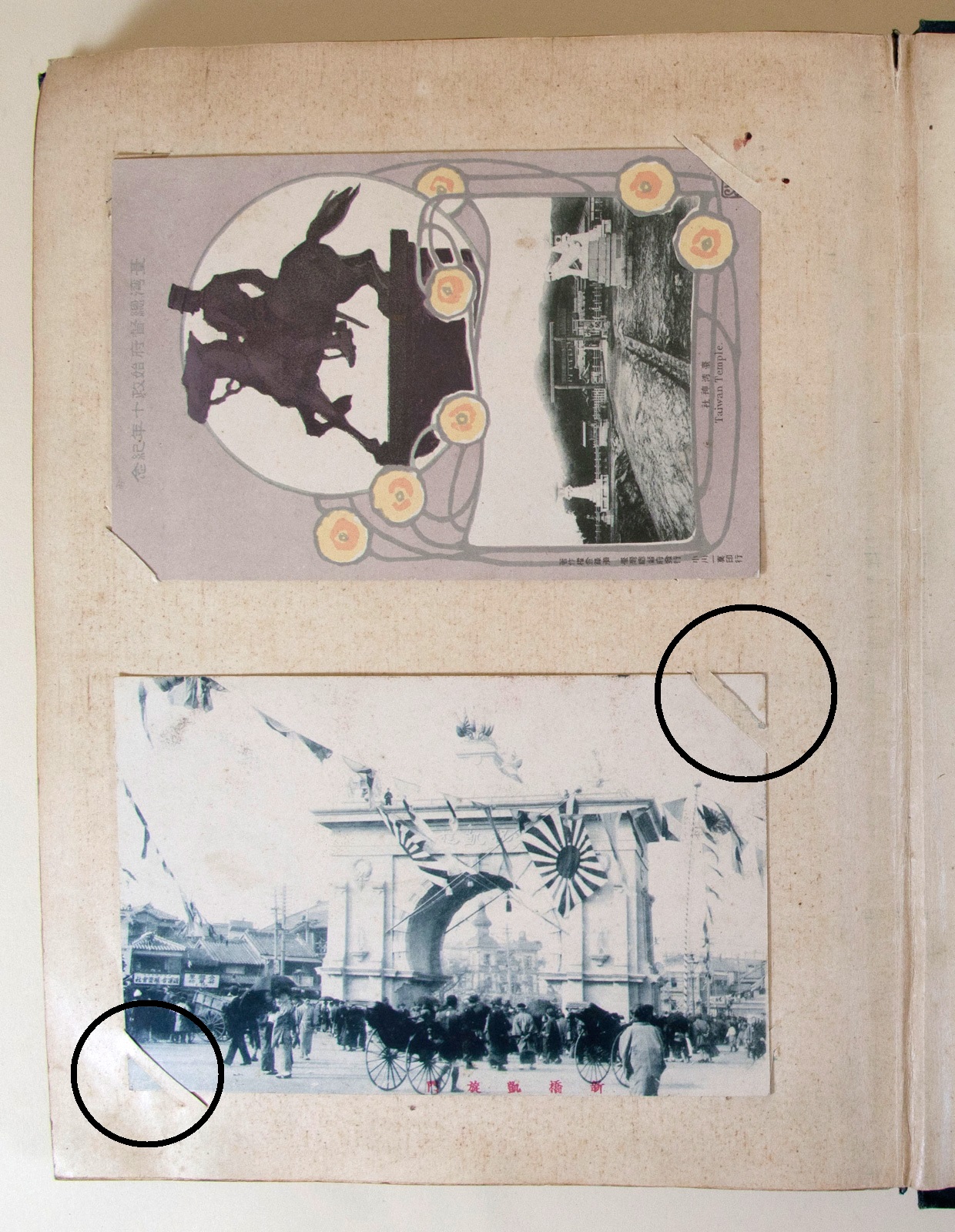

The diagonal yellow lines that cut the corners of the image simulate the fasteners that held picture postcards in place in collector’s albums at the time. This visual cue reminds us that this postcard was published at the height of a boom that saw hundreds of thousands of copies of some cards published under government auspices.

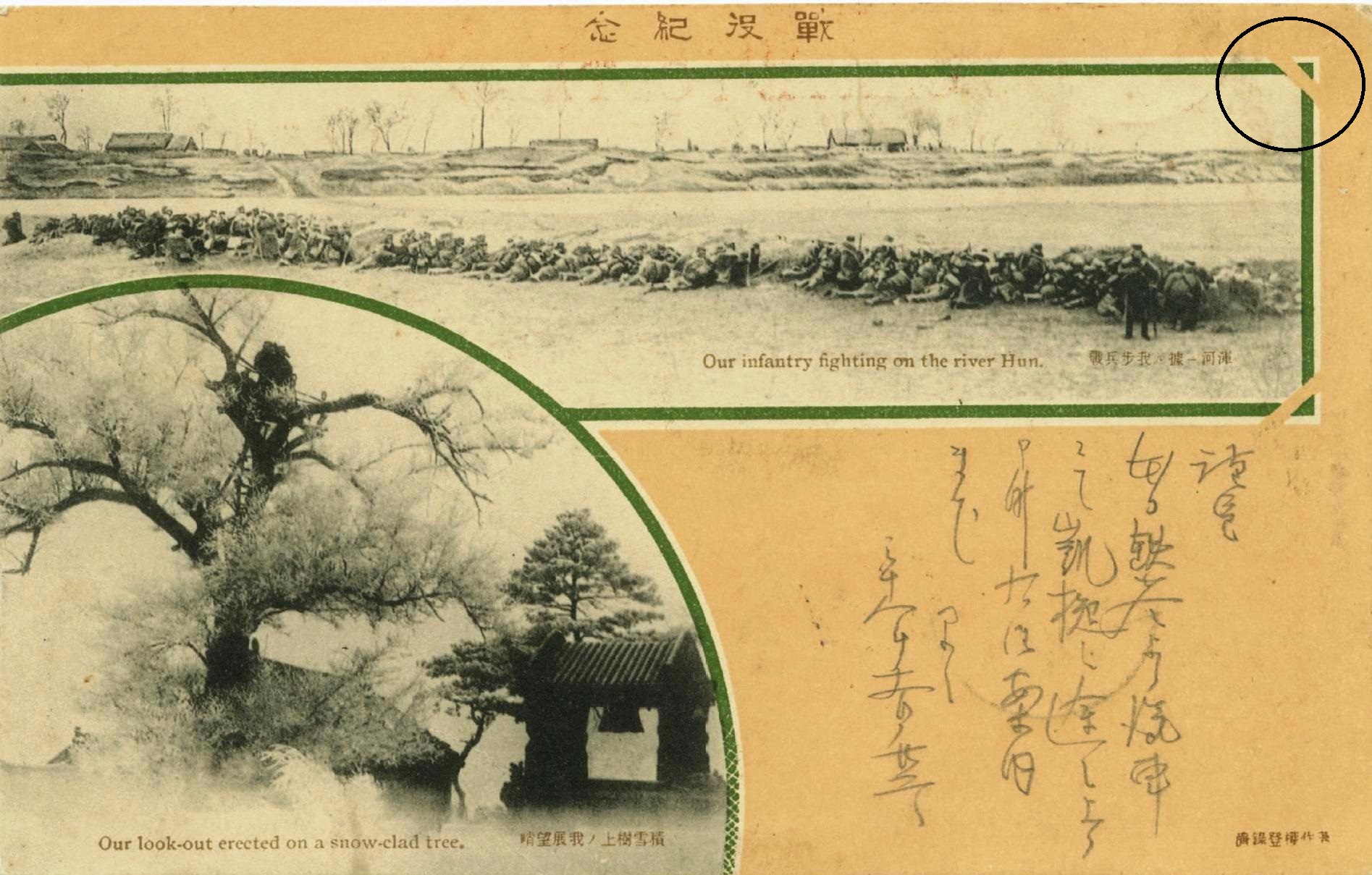

Here is a Russo-Japanese War card that employed the same design element, published on October 15th, 1905, with a print-run of 140,000 cards [6]:

Here is a Russo-Japanese War card that employed the same design element, published on October 15th, 1905, with a print-run of 140,000 cards [6]:

[rj0031] Our Infantry Fighting on the River Hun; Our Look-out Erected on a Snow-clad Tree

[rj0031] Our Infantry Fighting on the River Hun; Our Look-out Erected on a Snow-clad Tree

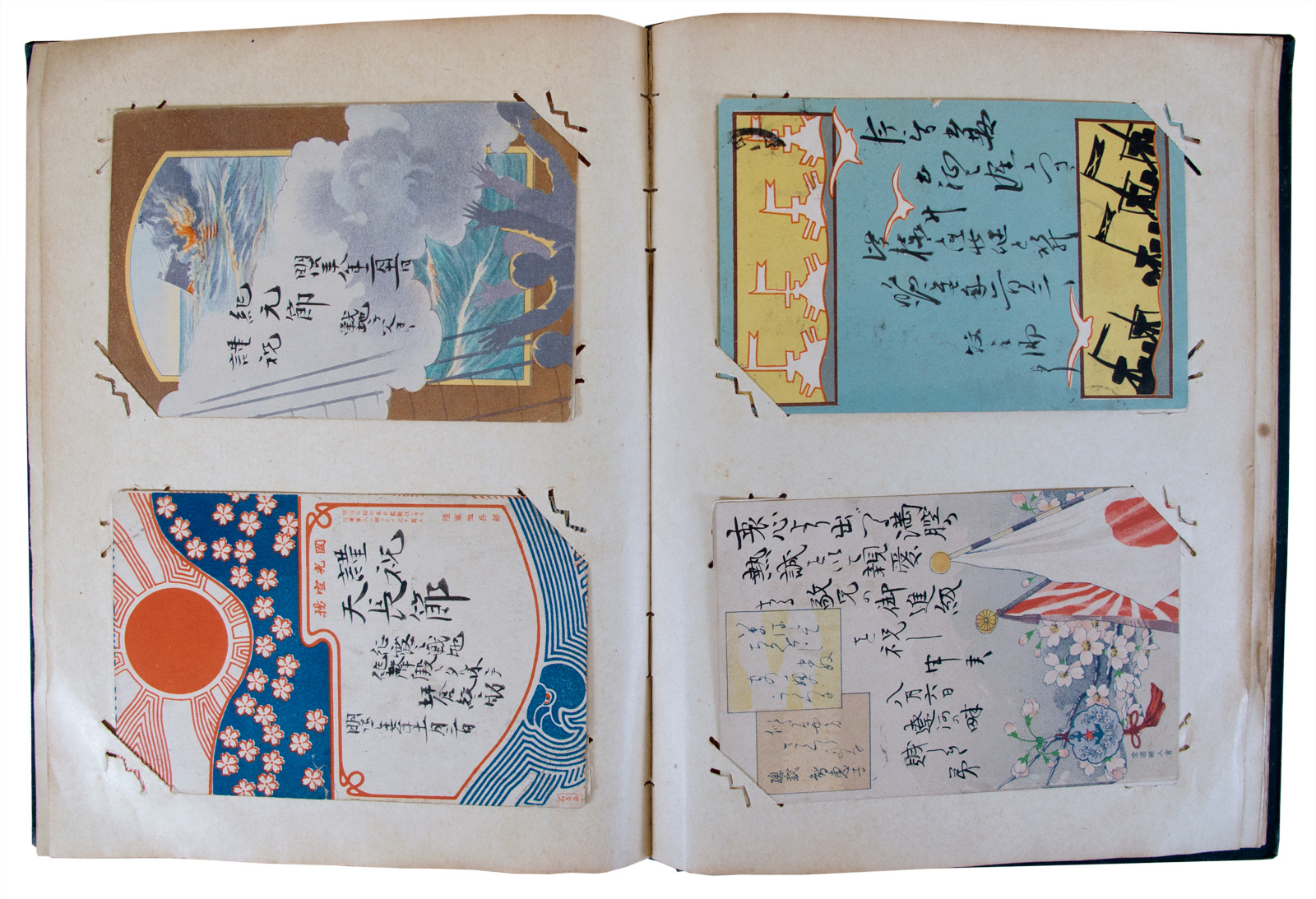

The postcard album below was assembled from 1904 to 1908 by the Tsubokura family of Tokyo. One of the Tsubokura boys was dispatched to Liaoning and worked in logistics; the album preserves correspondence between the front and Tokyo. These albums were common at the time (photograph by Eric Luhrs).

The top card in the image below (“Taiwan Temple”), is from the 10th anniversary set of the Taiwan Government General (its first officially issued set of postcards). Its presence in the Tsubokura album links the Taiwan cards to the Russo-Japanese War postcard boom, and illustrates the physical attachment mechanism that was easily recognizable to consumers at the time:

The top card in the image below (“Taiwan Temple”), is from the 10th anniversary set of the Taiwan Government General (its first officially issued set of postcards). Its presence in the Tsubokura album links the Taiwan cards to the Russo-Japanese War postcard boom, and illustrates the physical attachment mechanism that was easily recognizable to consumers at the time:

Official commemorative Russo-Japanese War cards were issued in print runs ranging from 30,000 to one million; the usual number was around 140,000 cards. Based on these numbers, it would not be reasonable to estimate that at least 50,000, if not more, Taiwan Government General 13th Anniversary cards (with the group portrait from 1874) were produced in 1908.

Official commemorative Russo-Japanese War cards were issued in print runs ranging from 30,000 to one million; the usual number was around 140,000 cards. Based on these numbers, it would not be reasonable to estimate that at least 50,000, if not more, Taiwan Government General 13th Anniversary cards (with the group portrait from 1874) were produced in 1908.

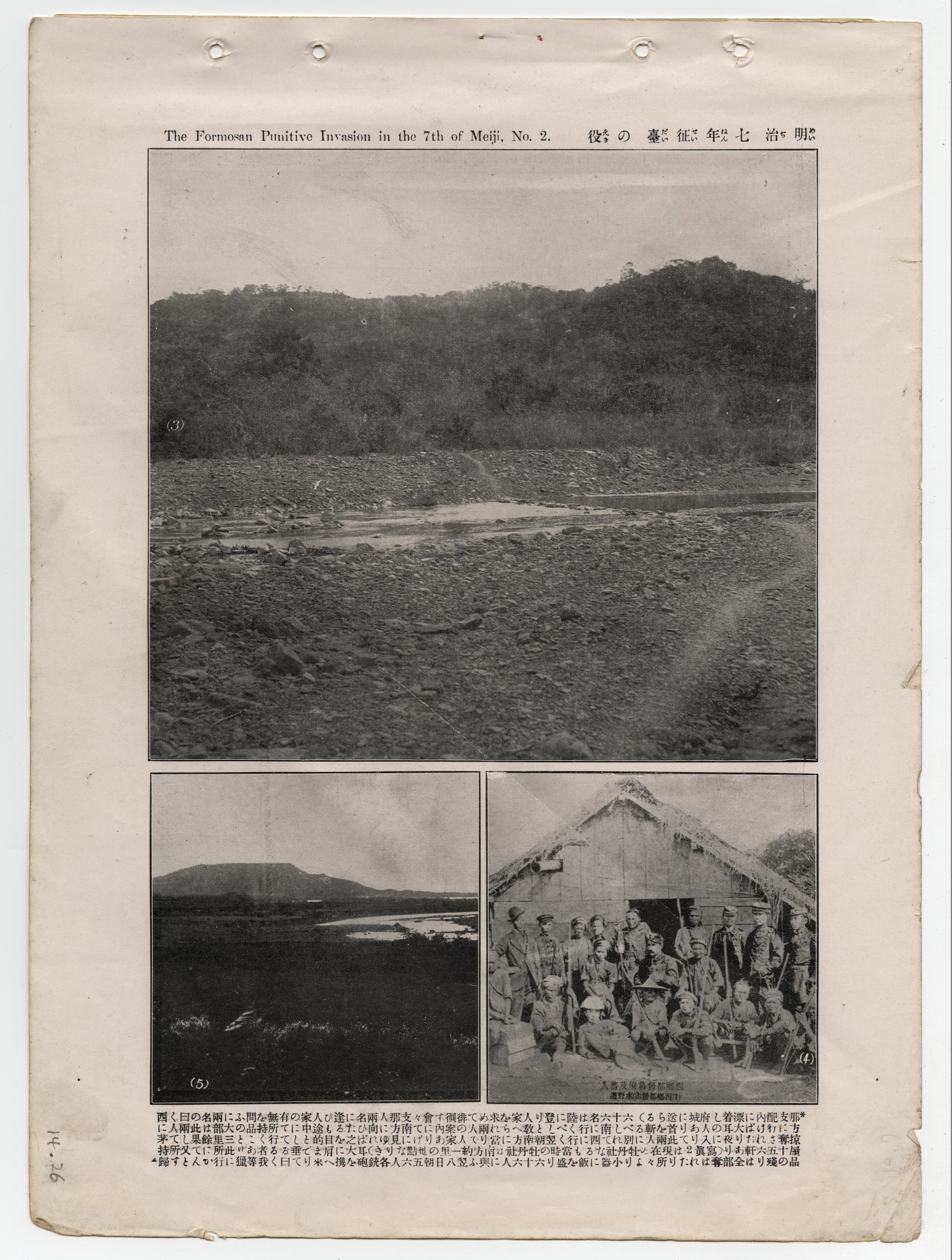

This postcard image, with caption intact, was reprinted in the January 1916 monthly issue of a Tainan based photography club’s journal. It was one of a 12-photograph series about the Expedition. Aside from reproducing the caption from the 1908 postcard, this reproduction adds no new knowledge about the contents or origins of the photograph. Its radical cropping, lack of explanatory text, and visual marginalization suggest that the editors did not think of the group portrait as an image central to the iconography of the Taiwan Expedition.

[ts0460] The Formosan Punitive invasion in the 7th of Meiji, No.2

[ts0460] The Formosan Punitive invasion in the 7th of Meiji, No.2

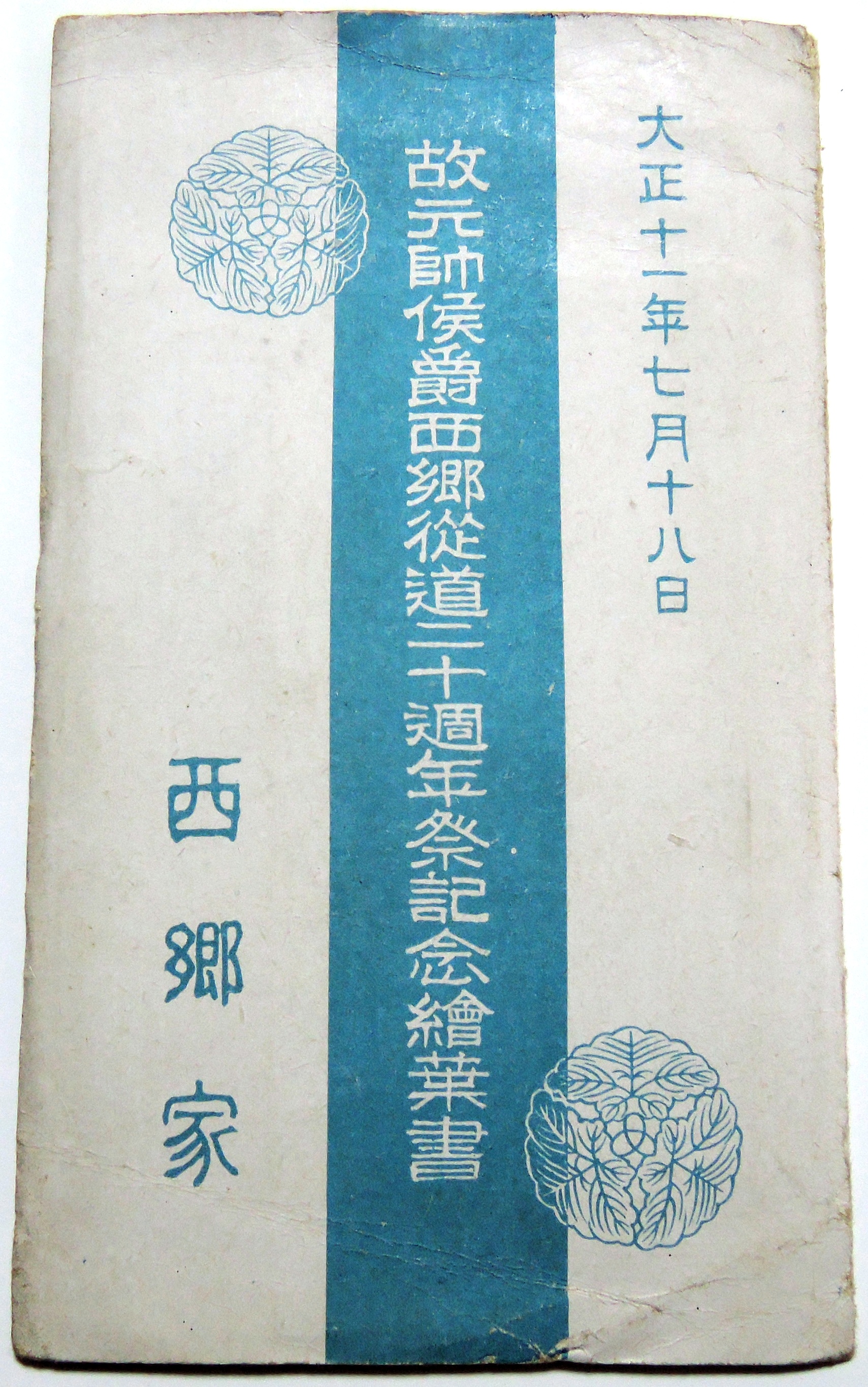

After its appearance in the album above in 1916, this photograph seems to have kept a very low profile. Yamamoto Yoshimi discovered a 6 postcard set published by Saigo’s family on the twentieth anniversary of Saigo Tsugumichi’s death (1922).

Envelope for six-postcard set published on the 20th anniversary of Saigo Tsugumichi’s death. From private collection of Professor Yamamoto Yoshimi.

Envelope for six-postcard set published on the 20th anniversary of Saigo Tsugumichi’s death. From private collection of Professor Yamamoto Yoshimi.

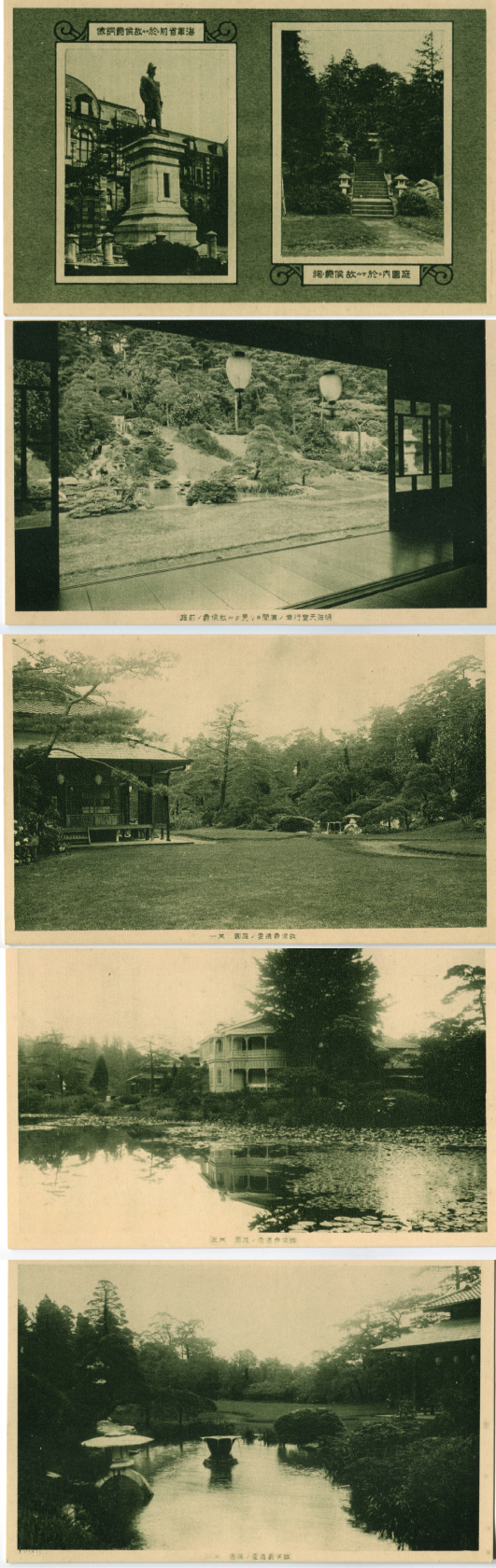

Five of the postcards are not connected to 1874:

Five of the six cards in Saigo Tsugumichi 20-year Death Anniversary Set, supplied by Professor Yamamoto Yoshimi.

Five of the six cards in Saigo Tsugumichi 20-year Death Anniversary Set, supplied by Professor Yamamoto Yoshimi.

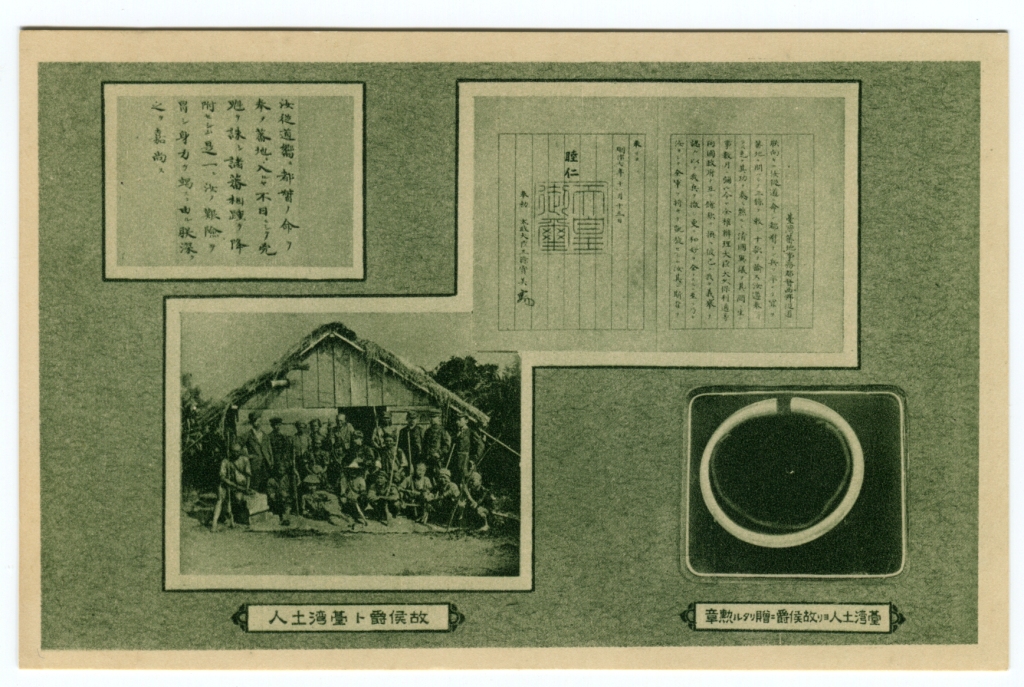

However, one postcard indeed includes the group portrait, along with a picture of a silver bracelet that Saigo reportedly received from one of the headmen (and did not remove from his wrist for the rest of his life), the Imperial Order to “subjugate the barbarians,” and a note describing the bracelet (Yamamoto 2007, 188):

Saigo Tsugumichi 20-year Death Anniversary Set, supplied by Professor Yamamoto Yoshimi.

Saigo Tsugumichi 20-year Death Anniversary Set, supplied by Professor Yamamoto Yoshimi.

There is a copy of this card in the National Central Library’s postcard database (故侯爵與臺灣土人 (National Central Library, Taipei #002414324), and all six postcards are held in microform copy at the Salt Lake City Family History Center in Utah, under the title 故元帥候爵西郷従道二十周年祭記念絵葉書).

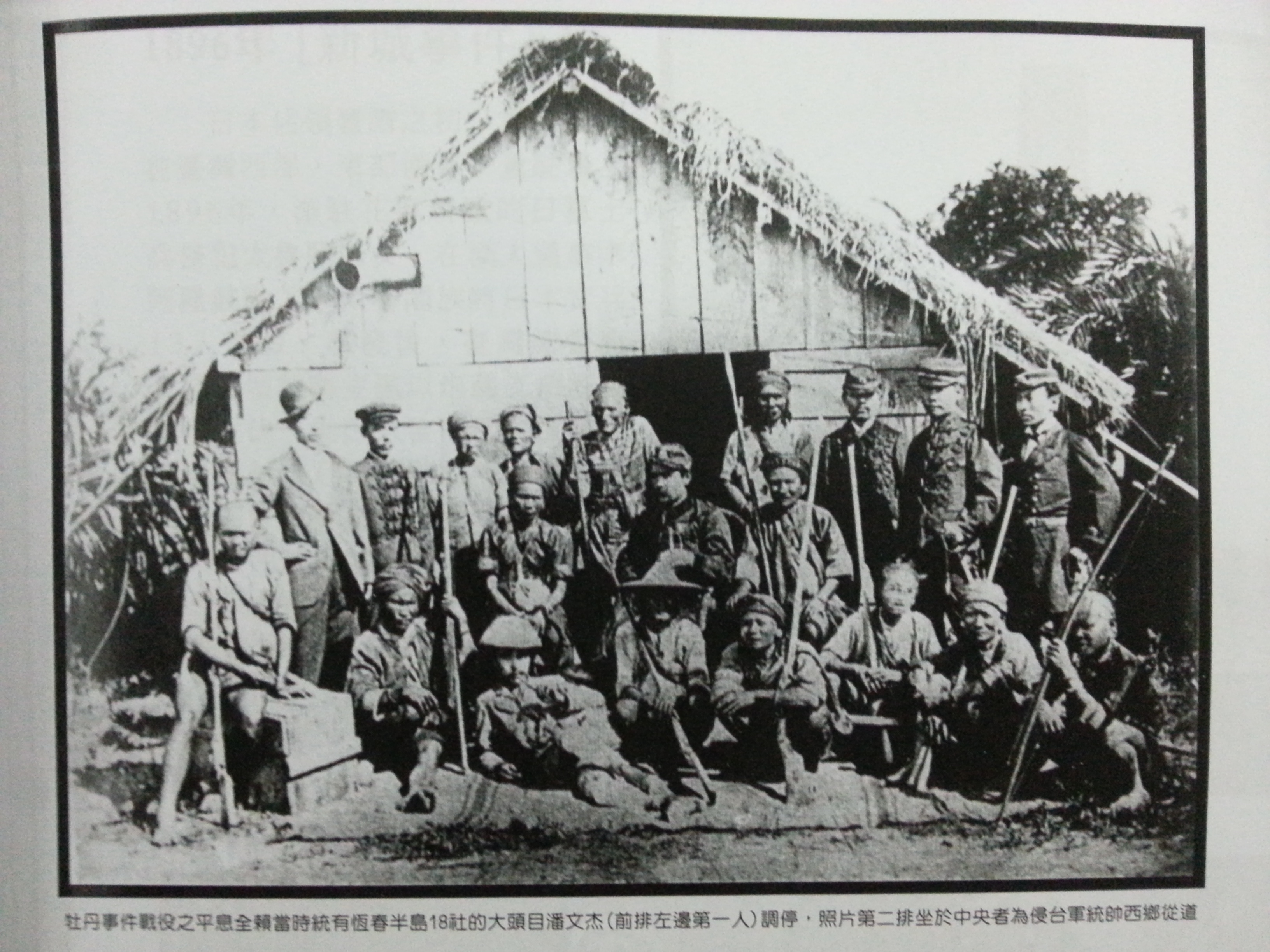

The photo was included in an imperial photo collection date the same year, 1922, called “Meiji-Taisho Trans-reign Commemorative Photograph Album.” 『明治大正連続記念写真帖 : 皇室軍事天変人事』. 東京:帝国記念協会. http://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/920136

In the mid-1930s, there was a Saigō boomlet that coincided with the rise of militarism and ultranationalism in the home islands and colonies. Saigō Totoku to Kabayama Sōtoku 西郷都督と樺山總督 was published in 1936. The editors thanked various supporters for raising money for an enormous 5000 yen subvention budget–this publication was indeed a labor-of-love. It is difficult to find an original copy today, suggesting that it had a small print run. This book was published to restore Saigo to a place of prominence in Taiwan’s history, it would seem. Unsurprisingly, then, Mizuno Jun’s name does not appear in the caption. Only Saigo is mentioned by name. In this 1936 version, the “savage settlement chiefs have been summoned-drafted 招集 to be separated out prior to the victory procession in order to be photographed with Commander Saigo.”

According to Professor Fix’s most recent analysis of the portrait, one the headmen sitting next to Saigo was quite possibly “Isa” (or “Esuck”) from Sabaree. Based his collation of a number of contemporary documents and his consultation of the 1936 account mentioned above, Fix also allows for the possibility that “Tokebunkya (土結文脚) from Churaso (豬勞束), Kareitai (加禮帶) from Monsui (蚊蟀), and Abiko (or Amiko 阿眉子) from Monsuiho (蚊蟀埔)” were present in the photograph. Yamamoto also provides this list, based on the same document, in her article. In addition, based on her reading of Kabayama Sukenori’s diary, Yamamoto also puts Isa/Esuck at the site of the photograph. As we have seen, Davidson also named Isa as a sitter for this photo. We can conclude from what is missing in these captions that Japanese image-makers and consumers were not much interested in Langqiao residents, or Paiwans, as individuals with names and biographies. Instead, they were content with general terms like “headman” “savage village” and “savage.” While there is much textual evidence to suggest that Langqiao political leaders considered themselves allies of the Japanese, and that some of them possessed formidable political, linguistic, and diplomatic skills, none of these considerations made it into the visual record I have been tracking in this post.

According to Professor Fix’s most recent analysis of the portrait, one the headmen sitting next to Saigo was quite possibly “Isa” (or “Esuck”) from Sabaree. Based his collation of a number of contemporary documents and his consultation of the 1936 account mentioned above, Fix also allows for the possibility that “Tokebunkya (土結文脚) from Churaso (豬勞束), Kareitai (加禮帶) from Monsui (蚊蟀), and Abiko (or Amiko 阿眉子) from Monsuiho (蚊蟀埔)” were present in the photograph. Yamamoto also provides this list, based on the same document, in her article. In addition, based on her reading of Kabayama Sukenori’s diary, Yamamoto also puts Isa/Esuck at the site of the photograph. As we have seen, Davidson also named Isa as a sitter for this photo. We can conclude from what is missing in these captions that Japanese image-makers and consumers were not much interested in Langqiao residents, or Paiwans, as individuals with names and biographies. Instead, they were content with general terms like “headman” “savage village” and “savage.” While there is much textual evidence to suggest that Langqiao political leaders considered themselves allies of the Japanese, and that some of them possessed formidable political, linguistic, and diplomatic skills, none of these considerations made it into the visual record I have been tracking in this post.

In the post-colonial period, as we have seen from the genealogy of drawings based on the group portrait, this image continues to circulate, and the captions and contexts continue to shift. Lin Chengrong’s 林呈蓉 The Truth about the Mudan Incident 牡丹社事件的真相 has perhaps followed Davidson in suggesting that Tokitok might present in the photograph. Incidentally, this claim is also reproduced on the Chinese Wikipedia page for Tokitok, which suggests that Davidson’s captioning has been taken at face value by a number of parties.

Lin Chengrong 林呈蓉, Mudan she shijian de zhenxiang 牡丹社事件的真相 (Xin Taipei: Boyang wenhua, 2006), p. 107.

The next reproduction is from a large collection of images organized around the theme of Indigenous resistance to Japanese imperialism, of which the 1874 Expedition forms the first chapter (in this narrative). The author of this book, Gen Zhiyou, has edited several other pictorial studies of Taiwanese resistance to Japanese rule as well as of the Atayal people. Novel to Gen’s usage of this image is his claim that the man seated in the front row all the way to the left is Pan Wenjie (潘文杰,Jagarushi Guri Bunkiet). I have not seen this claim in any study, and suspect that Saigo himself, as well as his family, would have trumpeted Pan’s presence if in fact Pan Wenjie had attended this get-together.

From: Gen Zhiyou 根誌優, 臺灣原住民族抗日史圖輯 : 1874-1933 = Collection of historical photographs of Taiwan’s indigenous people’s resistance against Japanese occupation. 臺北市 : 臺灣原住民, 2010.09.

From: Gen Zhiyou 根誌優, 臺灣原住民族抗日史圖輯 : 1874-1933 = Collection of historical photographs of Taiwan’s indigenous people’s resistance against Japanese occupation. 臺北市 : 臺灣原住民, 2010.09.

In addition to the above recent books, the group portrait decorates websites, Wiki entries, and coffee-table books that will continue to find many viewers. On this website, it illustrates an opinion piece about the Han Chinese oppression of Indigenous Peoples, both as the lead image and as an embedded issue. Perhaps it is a tribute to this photograph’s revival that it has nothing at all to do with the content of the article!

http://www.pure-taiwan.info/2014/12/indigenous-in-mountains

http://www.pure-taiwan.info/2014/12/indigenous-in-mountains

However widespread this photo has become, it probably was not the dominant image of the Japanese Expedition to Hengchun during the period of Japanese colonial rule. It seems more likely that grave markers and monuments, or even scenic views of Stone Gate, were more pervasive.

Leave a Reply