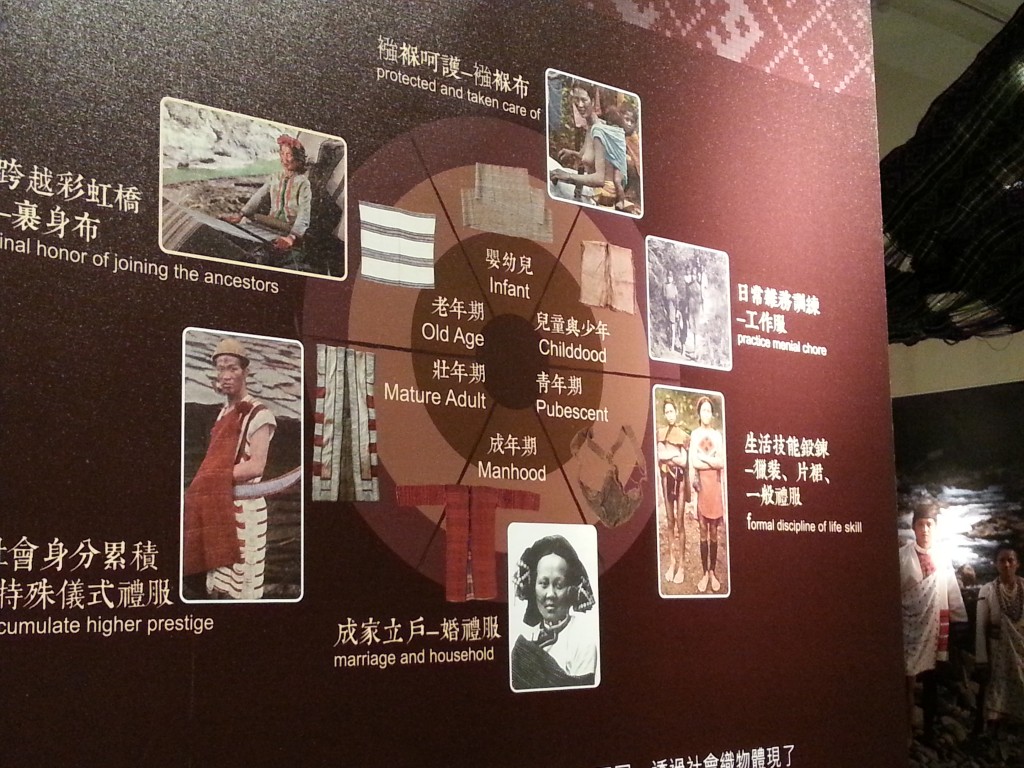

For a major exhibit titled ‘Rainbow and Dragonfly,’ held from Septemember 2014 through March 2015 at the National Taiwan Museum in Taipei, a large billboard greets visitors and passersby with four distinct examples of Atayal textile manufacture, of varied pattern and age, all dominated by the color red.

For this event, fully one-half of the palatial museum’s first floor is dedicated to Atayal fabrics, their sub-regional variations, and the process of preservation and revival.

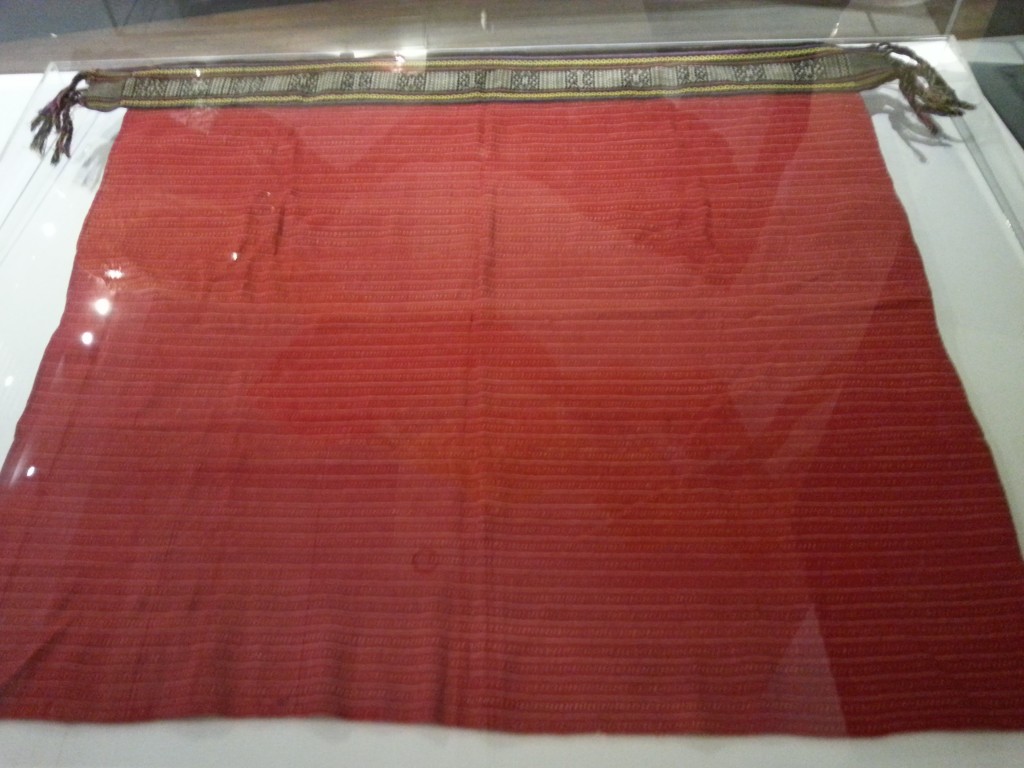

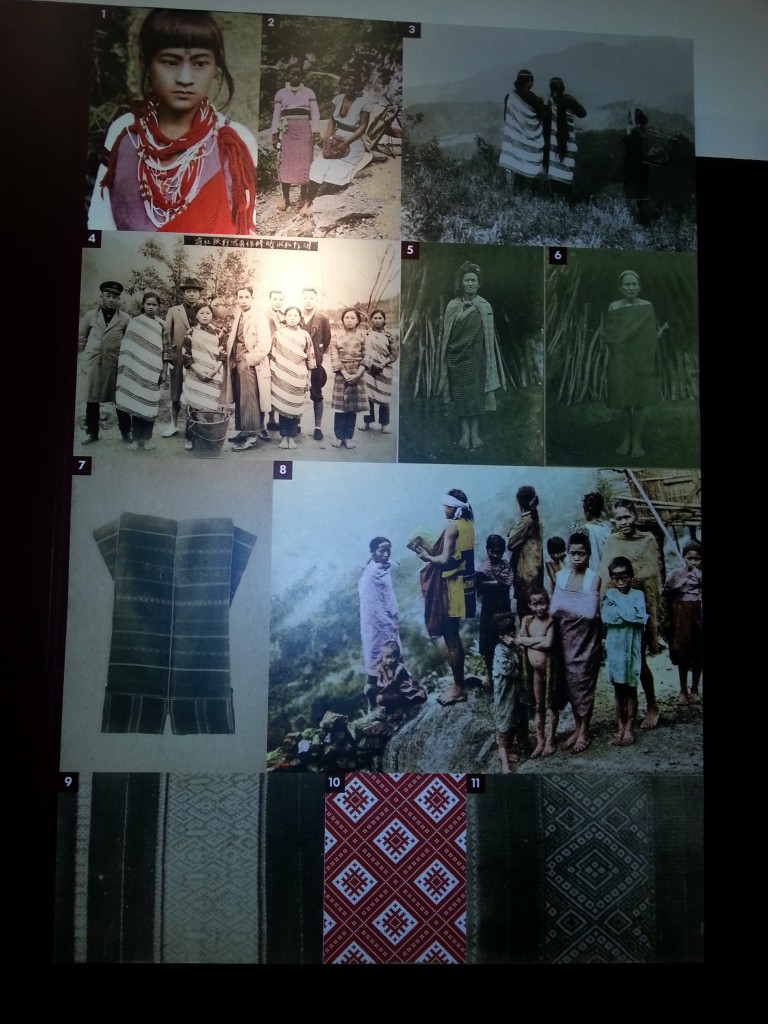

It is a complex installation: 100-year-old, disembodied fabrics are juxtaposed with updated patterns and colors on sleek black manikins:

It is a complex installation: 100-year-old, disembodied fabrics are juxtaposed with updated patterns and colors on sleek black manikins:

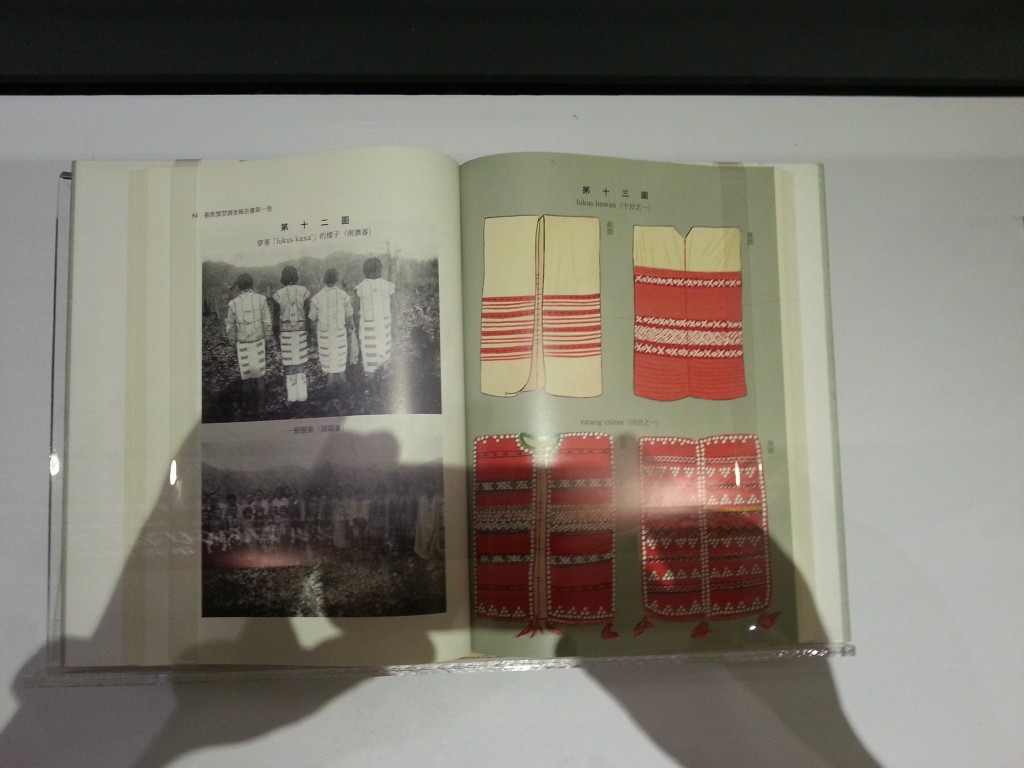

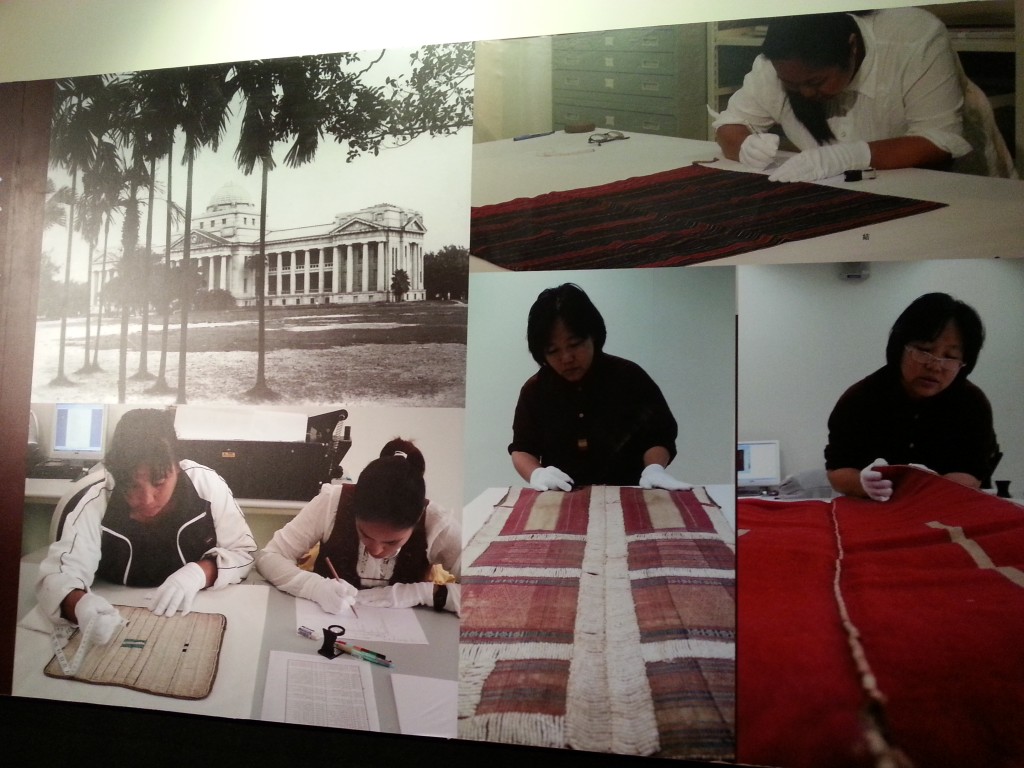

Colonial-era ethnological surveys share space with videos of contemporary weavers consulting them:

Colonial-era ethnological surveys share space with videos of contemporary weavers consulting them:

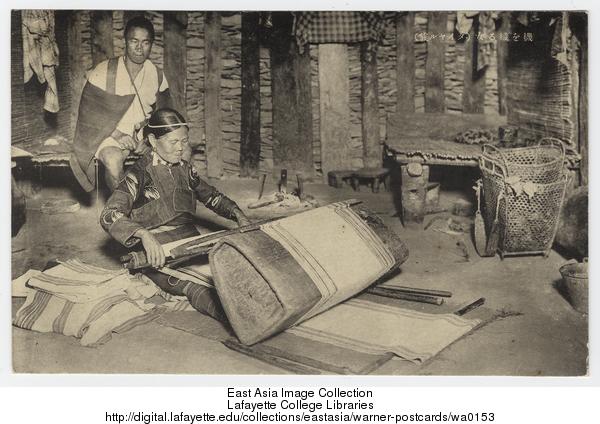

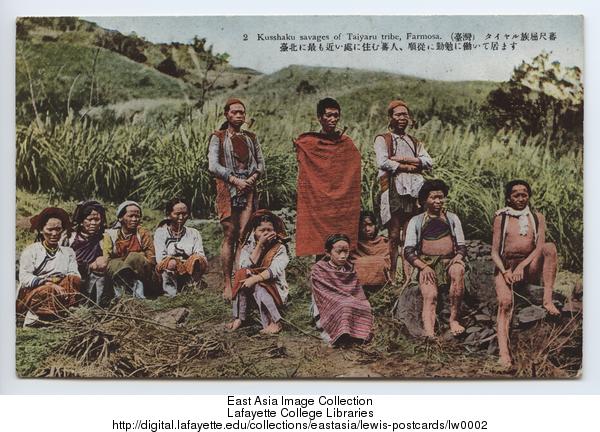

Japanese colonial-era postcards are dispersed amongst the exhibits to illustrate the diversity, antiquity, and centrality of the displayed fabrics.

Japanese colonial-era postcards are dispersed amongst the exhibits to illustrate the diversity, antiquity, and centrality of the displayed fabrics.

The building itself is part of this story. The Taiwan National Museum in Taipei was established by the Taiwan Government General in 1908, while its current structure was completed in 1915.

The building itself is part of this story. The Taiwan National Museum in Taipei was established by the Taiwan Government General in 1908, while its current structure was completed in 1915.

The Rainbow and Dragonfly exhibit, housed in a neo-classical neo-colonial edifice, is in good measure a dusting off, repackaging, and repurposing of the artifacts collected among Indigenous Peoples during the Japanese occupation.

The Rainbow and Dragonfly exhibit, housed in a neo-classical neo-colonial edifice, is in good measure a dusting off, repackaging, and repurposing of the artifacts collected among Indigenous Peoples during the Japanese occupation.

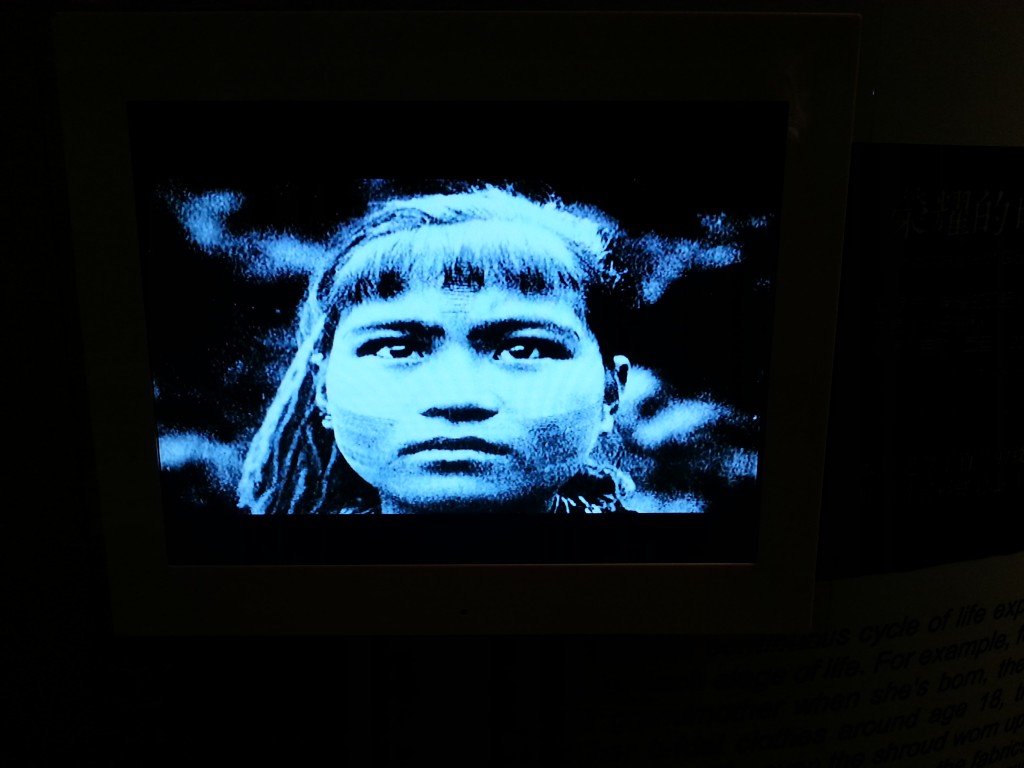

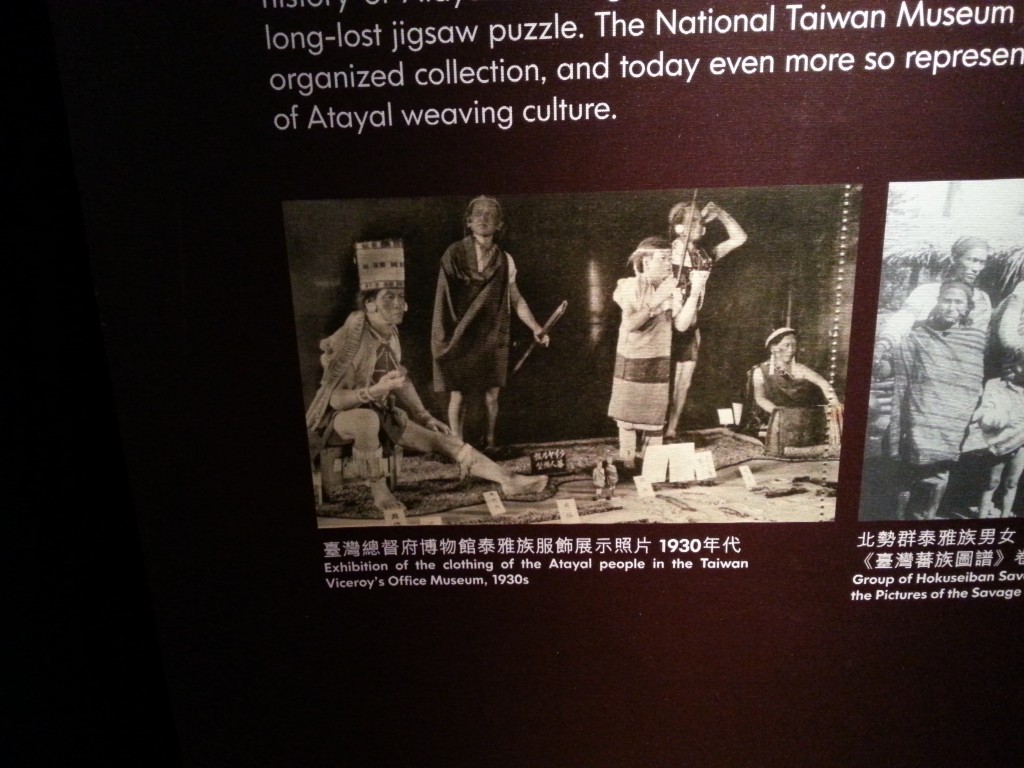

This weekend, there will be a special lecture about the textiles. Its sign uses an image quite familiar to me:

This weekend, there will be a special lecture about the textiles. Its sign uses an image quite familiar to me:  Here’s the 1930s postcard:

Here’s the 1930s postcard:

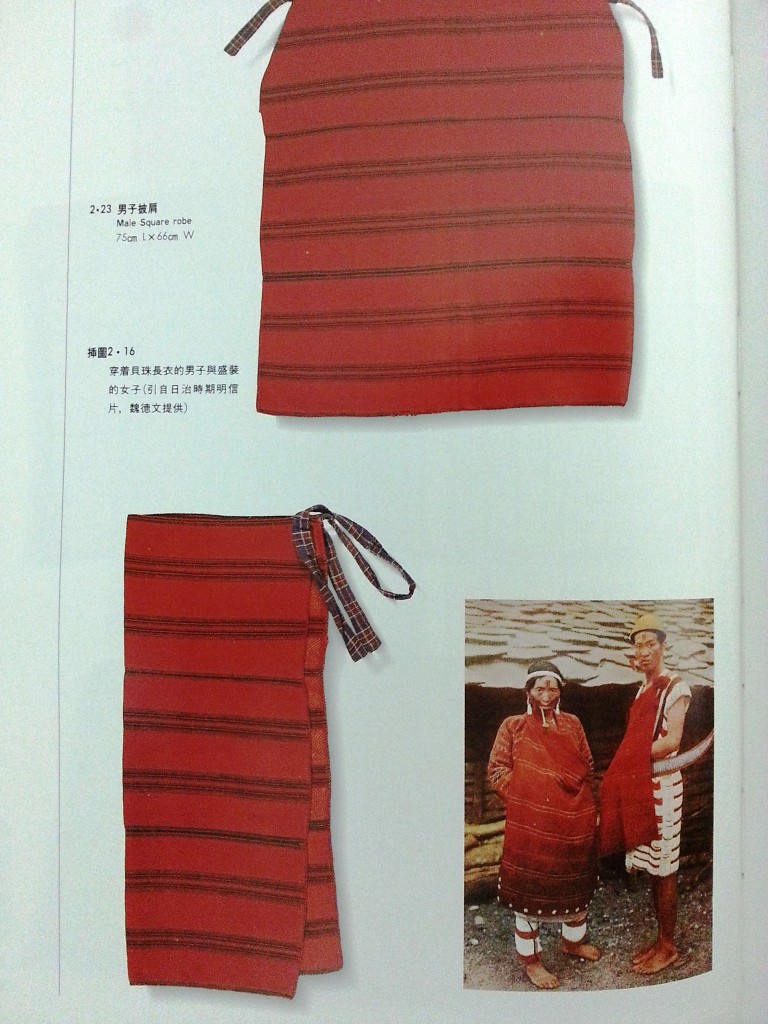

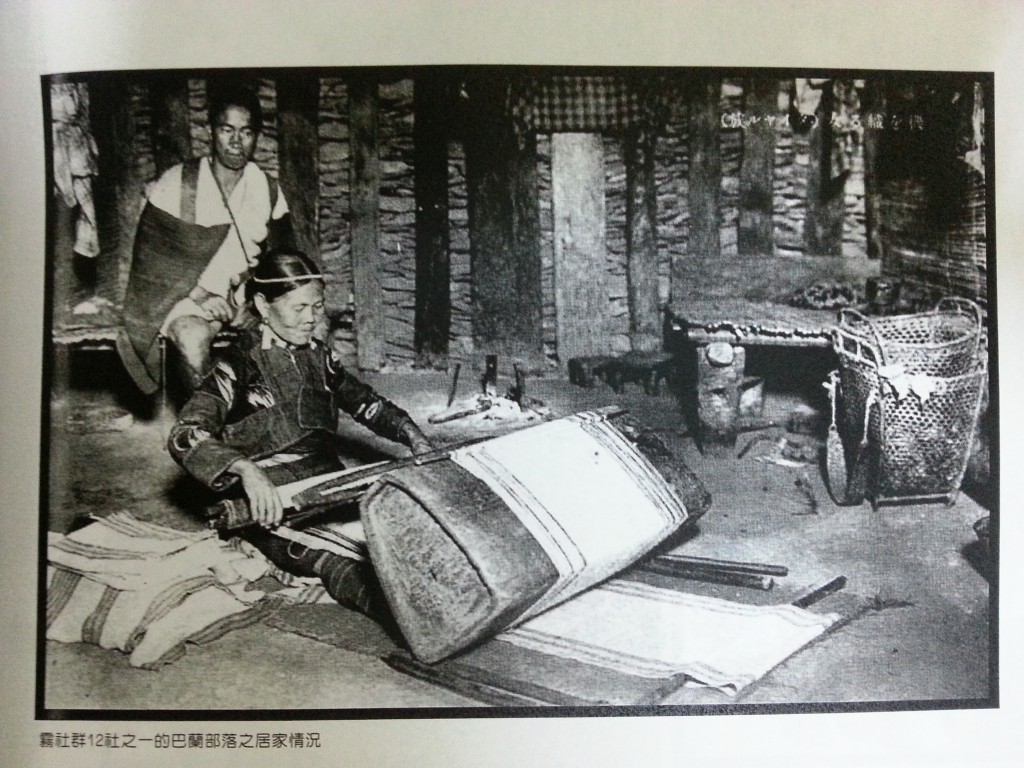

Here’s a reproduction in a recently published book:

Here’s a reproduction in a recently published book:

From: Gen Zhiyou 根誌優, 臺灣原住民族抗日史圖輯 : 1874-1933 = Collection of historical photographs of Taiwan’s indigenous people’s resistance against Japanese occupation. 臺北市 : 臺灣原住民, 2010.09.

From: Gen Zhiyou 根誌優, 臺灣原住民族抗日史圖輯 : 1874-1933 = Collection of historical photographs of Taiwan’s indigenous people’s resistance against Japanese occupation. 臺北市 : 臺灣原住民, 2010.09.

In short, this exhibit brings together the colonial past, the multicultural present, the Japanese imperializing mission, and Indigenous cultural renaissance under one roof into a plausibly coherent visual assemblage and narrative framework. It has been said that the political and intellectual climate of post-martial law Taiwan almost overdetermines positive endorsements of the Japanese occupation, or at least a willingness to entertain the possibility that it was not an unmitigated tale of exploitation, destruction, and mayhem. Indeed, the ‘Rainbow and Dragonfly’ exhibit is a centally located, nationally funded installation that characterizes the Taiwan Government General’s mission to collect, categorize, preserve, and display Atayal textiles as an heroic enterprise.

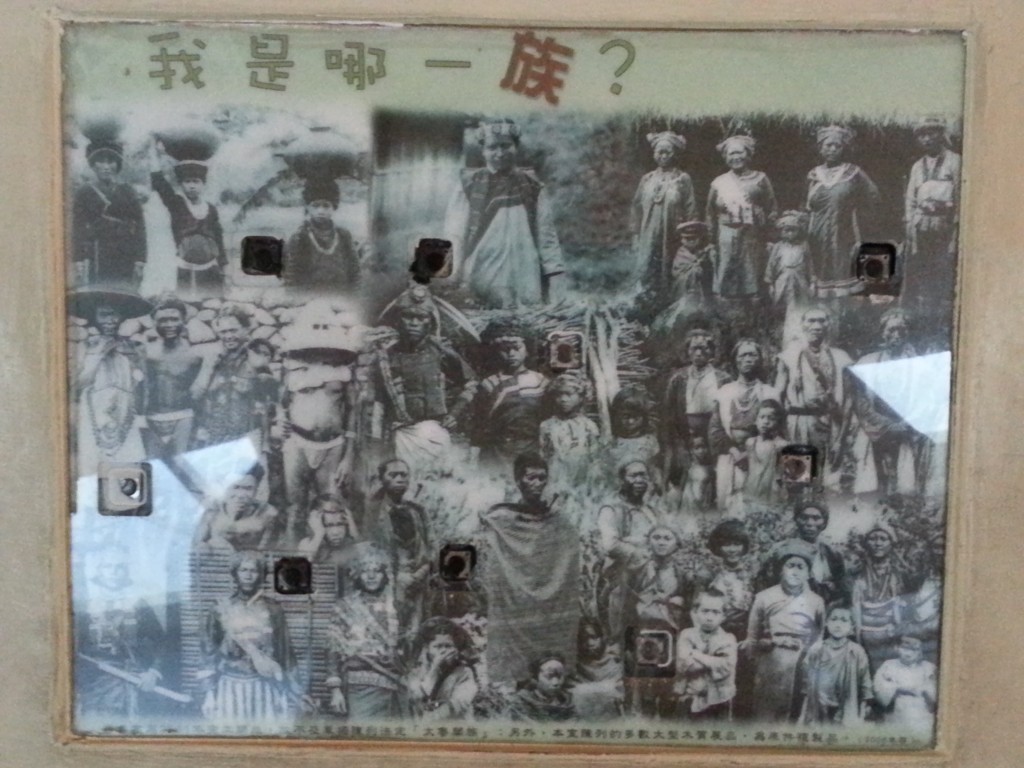

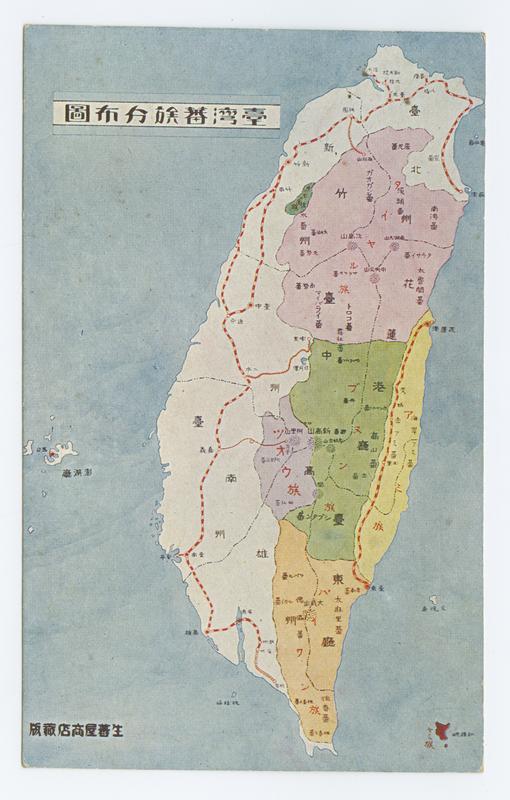

Of course, this exhibit does not exist in isolation. Neither does it convey a simple message, or one that I would reduce to “nostalgia,” “the invention of tradition,” or the “imperialist gaze.” One the one hand, there is simply institutional continuity at work. Below are a few snapshots for the permanent exhibition for Taiwan Indigenes, to use the museum’s language. Here we find displays that would not have been out of place in 1920, and some of which may very well date back to this period (I’m thinking especially of the map here, but also the photo montage of Mori Ushinosuke portraits):

Of course, this exhibit does not exist in isolation. Neither does it convey a simple message, or one that I would reduce to “nostalgia,” “the invention of tradition,” or the “imperialist gaze.” One the one hand, there is simply institutional continuity at work. Below are a few snapshots for the permanent exhibition for Taiwan Indigenes, to use the museum’s language. Here we find displays that would not have been out of place in 1920, and some of which may very well date back to this period (I’m thinking especially of the map here, but also the photo montage of Mori Ushinosuke portraits):

display at the National Taiwan Museum, permanent exhibit: “Which Tribe do I belong to?”

display at the National Taiwan Museum, permanent exhibit: “Which Tribe do I belong to?”

1930s Japanese postcard based on a 1902 photograph.

1930s Japanese postcard based on a 1902 photograph.

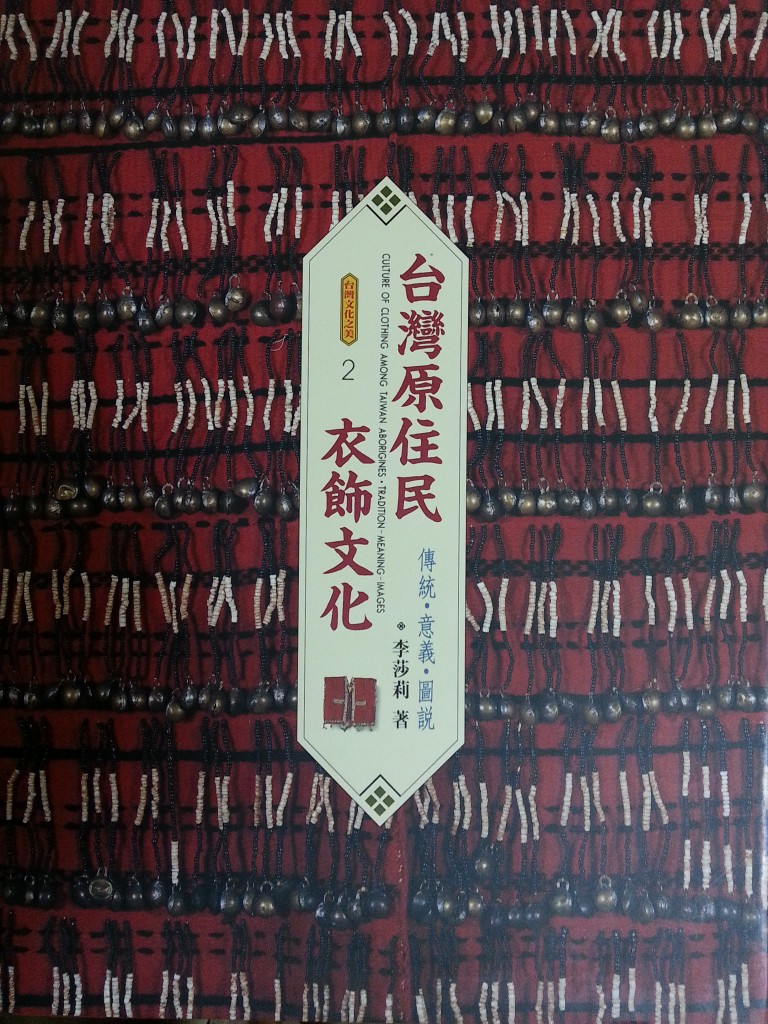

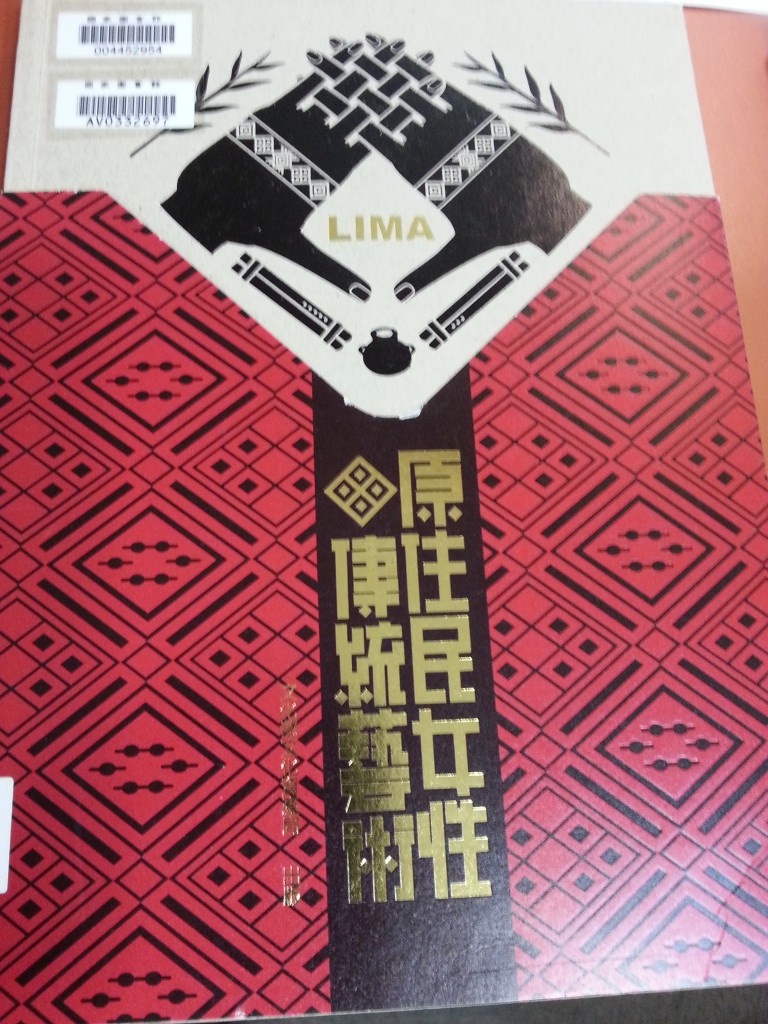

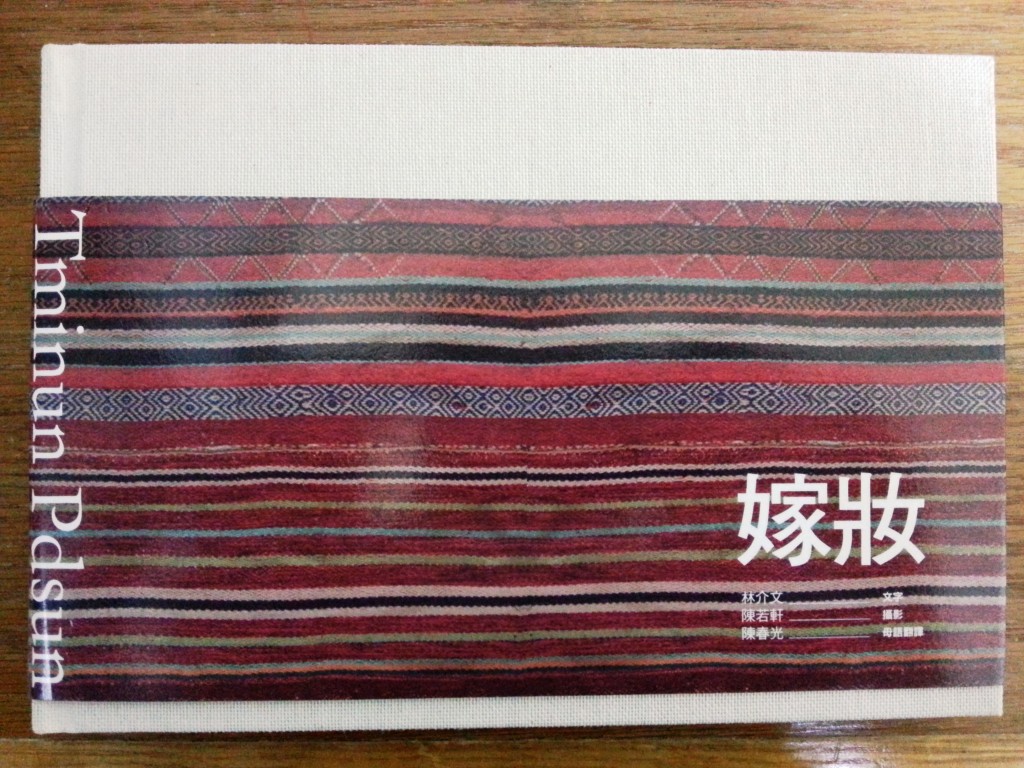

In addition to the inertia of using displays that have been around for years, the museum also seems to be keeping abreast of currents in modern publishing culture. Here are some book covers I’ve snapped in bookstores and libraries that exemplify the commercial and cultural renaissance in Atayal textiles:

Barely beneath its surface is the message that Japanese colonial ethnography, museum practices, and photography were (and remain) active partners in the sustenance and revival of Atayal culture, which is also packaged in this exhibit as an element of Taiwan’s national heritage. The national maps that festoon the exhibit mark out generous territorial units to represent the Atayal and Paiwan areas as geo-bodies within the geo-body of Taiwan. The vision expressed forecloses the possibility of imagining modernity without its indigenous other, or indigeneity without its modern other.

Barely beneath its surface is the message that Japanese colonial ethnography, museum practices, and photography were (and remain) active partners in the sustenance and revival of Atayal culture, which is also packaged in this exhibit as an element of Taiwan’s national heritage. The national maps that festoon the exhibit mark out generous territorial units to represent the Atayal and Paiwan areas as geo-bodies within the geo-body of Taiwan. The vision expressed forecloses the possibility of imagining modernity without its indigenous other, or indigeneity without its modern other.

I end the post by noting that I am so familiar with the photographs, photographers, and scenes used by this exhibit that I could write a very long scholarly article on the themes hinted at here. This post would never end if I were dig into the this material rigorously. For now, I post it in the hopes that people in Taiwan will go over to the Memorial Park/Museum area and catch the exhibit–it is wonderful. For people not in Taiwan, please consider a visit. Or if not a visit, could you please do some serious research on Navajo textiles, their role in native-newcomer relations, and the history of the their preservation, revival, and function in contemporary society? thanks.

I end the post by noting that I am so familiar with the photographs, photographers, and scenes used by this exhibit that I could write a very long scholarly article on the themes hinted at here. This post would never end if I were dig into the this material rigorously. For now, I post it in the hopes that people in Taiwan will go over to the Memorial Park/Museum area and catch the exhibit–it is wonderful. For people not in Taiwan, please consider a visit. Or if not a visit, could you please do some serious research on Navajo textiles, their role in native-newcomer relations, and the history of the their preservation, revival, and function in contemporary society? thanks.

Leave a Reply