Below are visualizations of the results from my study of 60 films featuring a femme fatale character. I have presented the breakdown of what crimes / villainous acts were committed in total throughout all 60 films, all of the methods used to commit these crimes, the motivations for the femme fatales to commit these crimes, and the repercussions suffered by these women. I have also visualized the data I collected on the race or ethnicity of the actors playing the femme fatales, and whether the femme fatales were the main characters of the films they were presented in.

Below each data visualization I have written my own interpretation and analysis in relation to how the data helps answer my research question. I have provided the data visualization, as well as the original dataset in the form of a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (link at the bottom of this page) so that my readers can examine the data for themselves in order to come to their own conclusions.

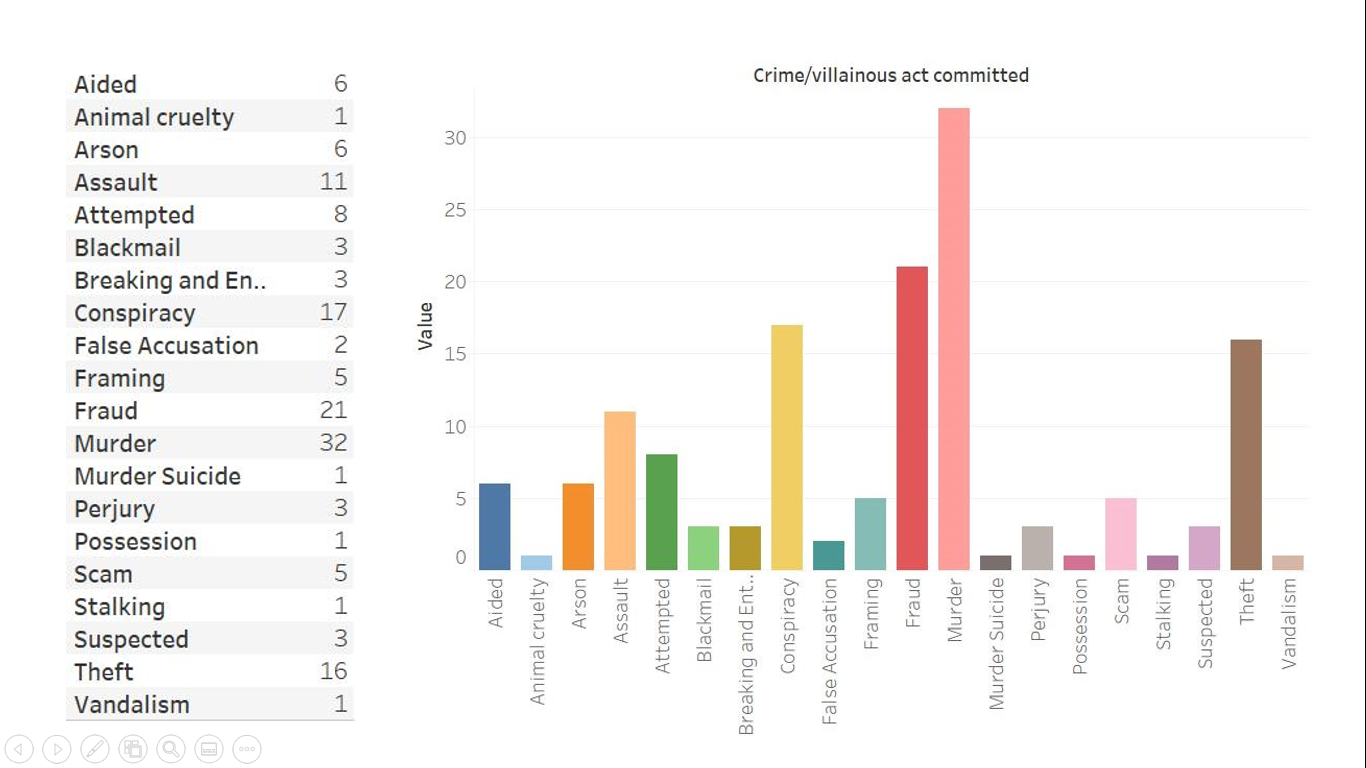

It is clear from this graph above that non-violent drug offenses are not well represented in these films, despite being one of the most common offenses committed by women. There is a total of one drug offense (“Possession”). There is a better representation of property offenses as, in total there were 16 thefts, six cases of arson, three cases of breaking and entering and one case of vandalism. Many of the offenses committed by the femme fatales in these 60 films are violent as there are 32 cases of murder, 11 cases of assault, eight cases of attempted murder, six cases of aiding someone to commit murder, three cases of suspected murder and one murder suicide. Overall, it seems as though these films focus more on presenting women as violent and murderous, rather than as perpetrators of non-violent drug and property crimes.

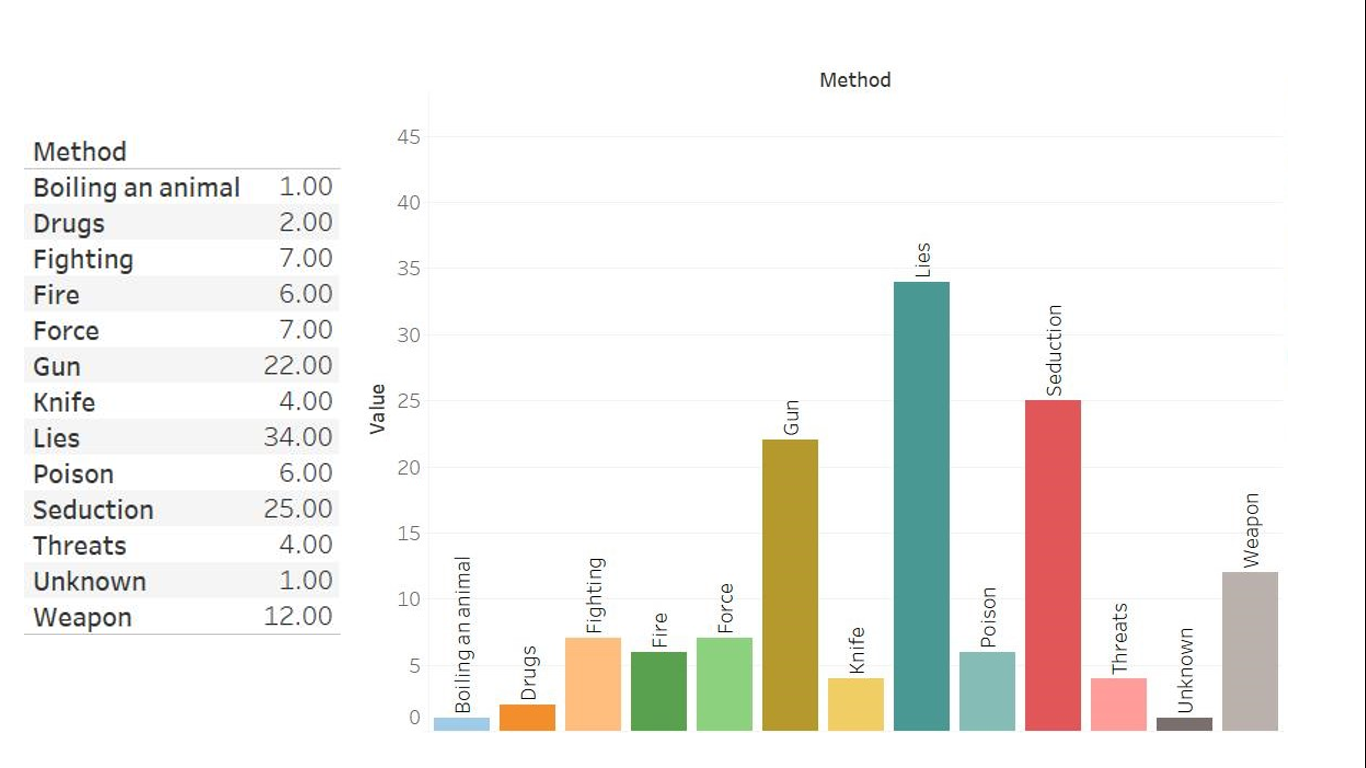

The key reason why I recorded the methods used by these femme fatales was to see how often seduction and lies were used by these women. Central to the original film noir femme fetale was her ability to seduce and manipulate men and commit crime for her own gain. I found that many of the femme fatales in these films conformed to this as they used seduction (25 instances) and lies (34 instances) to commit their crimes. Apart from these methods, guns (22 instances) and weapons (12 instances) made up a high proportion of the methods used by the femme fatales.

Understanding the femme fatale’s motivations to commit crime provides a central point of comparison between film and reality because this data can elucidate on how gendered pathways, central to the reality of female criminality, are presented in films. Daly’s gendered pathways approach help identify women’s motivations to commit crime, which often center around ensuring survival, often by escaping abusive households or providing themselves with the means to live. My main question when compiling this data was ‘do these femme fatales commit crime for the same reason that ‘real female criminals’ commit crime?’

On the surface, the answer to that question may be ‘yes.’ One third (29 out of 87) of the apparent motivations for these women to commit crime was ‘money.’ One may look at this data and think that this fits in with Daly’s gendered pathways approach which identifies that many women commit crime in order to financially provide for themselves. However, if you watch these films you will see how many of these women committed crime for money out of greed. For example, there were many women who attempted or succeeding in killing their husbands for his life insurance pay out. As such, rather than showing how women commit crime to gain money as a means of survival, this data shows that women are motivated by greed.

Nearly half of these motivations are connected to the women’s emotions: anger, insanity, jealousy, love, obsession, revenge and sociopathy. In some way, the exposition of emotion as a motivation to commit crime conforms to the gendered pathways approach, especially when it comes to the categories of ‘harmed and harming women’ and ‘battered women.’ Many of these women do commit crime out of anger or revenge because of how they had been mistreated, often by men. This could also account for the two instances of self defense. However, I argue that the other emotions such as insanity, jealousy, love, obsession and sociopathy, instead support the misogynistic belief that women are dangerous when they are unable to control their emotions. These women are seen as vulnerable and easily mislead if they commit crime because of love e.g. the influence of a boyfriend, or as selfish and irrational if they commit crime because of insanity or jealousy, for example. What this does not show us is the difficult and specifically gendered ways women are put in positions where they need to commit crime. Therefore, broadly speaking the motivation these femme fatales have to commit crime does not accurately present the motivations real female criminals have, particularly in accordance with Daly’s gendered pathways approach.

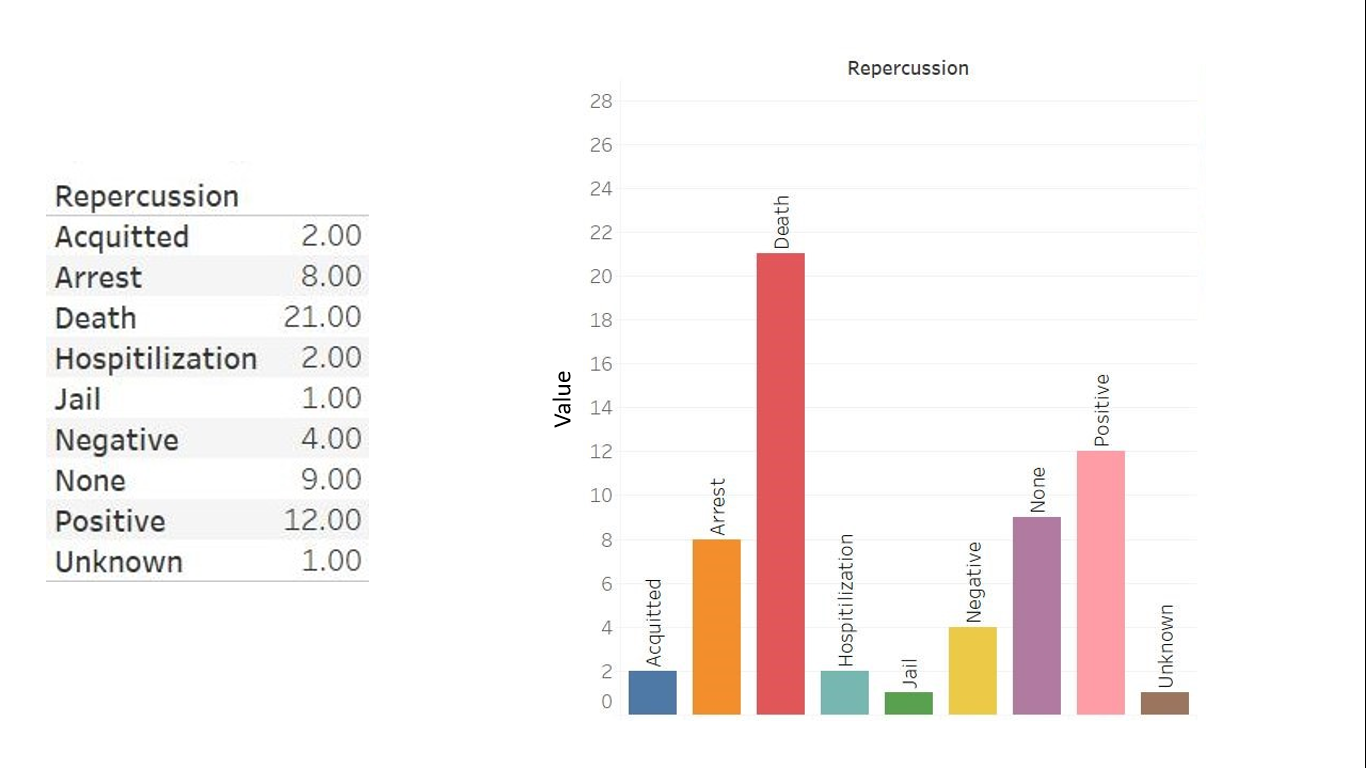

This graph shows, out of the 60 femme fatales explored, only 11 of these women suffered repercussions that involved law enforcement (two were acquitted of charges, eight were arrested, and one went to jail.) This is an extremely interesting set of data because it is difficult to know how many women, out of all the women in America who commit crime, are caught and become involved in law enforcement. Further, as the data below identifies, the overwhelming majority of these criminal women are white. Therefore, this data result could be accurate. It could be that only a minority of white women who commit crime become involved in law enforcement, therefore making this data an accurate representation of real female criminality. Unfortunately, we do not have the evidence to support this. What we do know is that in the US, a high proportion of incarcerated women are women of color. Thus, it is hard to assess the accuracy of the presentation of the repercussions female criminals suffer, when the majority of these female criminals are white.

What this data does show us, however, is that the femme fatales of these films are not as likely to become involved in law enforcement as they are to die or experience a positive repercussion. These films see 21 deaths and 12 positive endings for the femme fatale. The death of the femme fatale is central to the tradition of film noir, which is the main reason why the number of deaths in these films is so high. In this tradition, the evil force of the film, the femme fatale, must die in order to restore balance to the world of the film. You can read about how the femme fatale of the 1940s-1950s was also presented as a manifestation of male insecurity about women’s liberation, and was therefore a character that needed to be destroyed, on ‘The Femme Fatale in Hollywood‘ page. The high number of positive endings for the femme fatales is indicative of how these films attempt to glorify female criminality and show that there are no negative consequences for women who commit crime. There is perhaps an interesting argument here about specifically white female crime, however I think this data primarily shows us that films do not show the reality of the consequences that female criminals suffer.

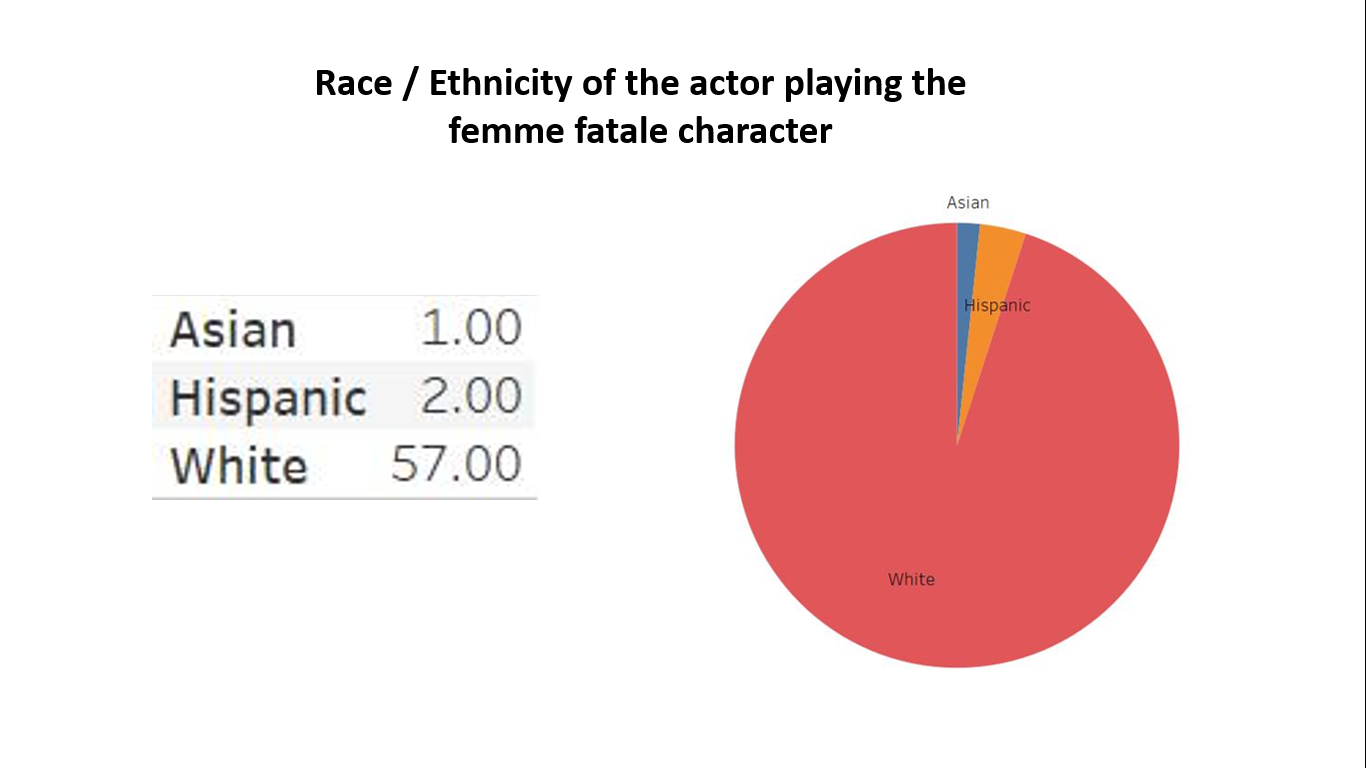

The data above shows that 95% of the women who portray the criminal character of the femme fatale in these American films are white. There is only one Asian woman and two Hispanic women who portray these characters. There are no black women who play femme fatales. One of the key explanations for this is that these films are American films and Hollywood is a notoriously racist organization that lacks diversity in terms of gender and race. Further, the films I have explored date back to the 1940s when people of color suffered even more extreme prejudice in all aspects of society, than they currently do, meaning they were never given opportunities to star in American films. Hollywood’s history of racism is explicit as it is only in the early 2000s and 2019 that the these Asian and Hispanic women are represented. Of course, these films are not representative of all American films, and therefore this data cannot be completely generalized. However, this data does serve as a powerful example of the extreme lack of diversity present in the US film industry.

Furthermore, this data serves as clear evidence for how American films featuring femme fatales are not accurate in their presentation of female criminality. Almost all of these women presented are white, when we know from the scholarly work explored in this project that communities of people of color are disproportionately affected by crime policies, meaning that a high percentage of incarcerated women and men are people of color.

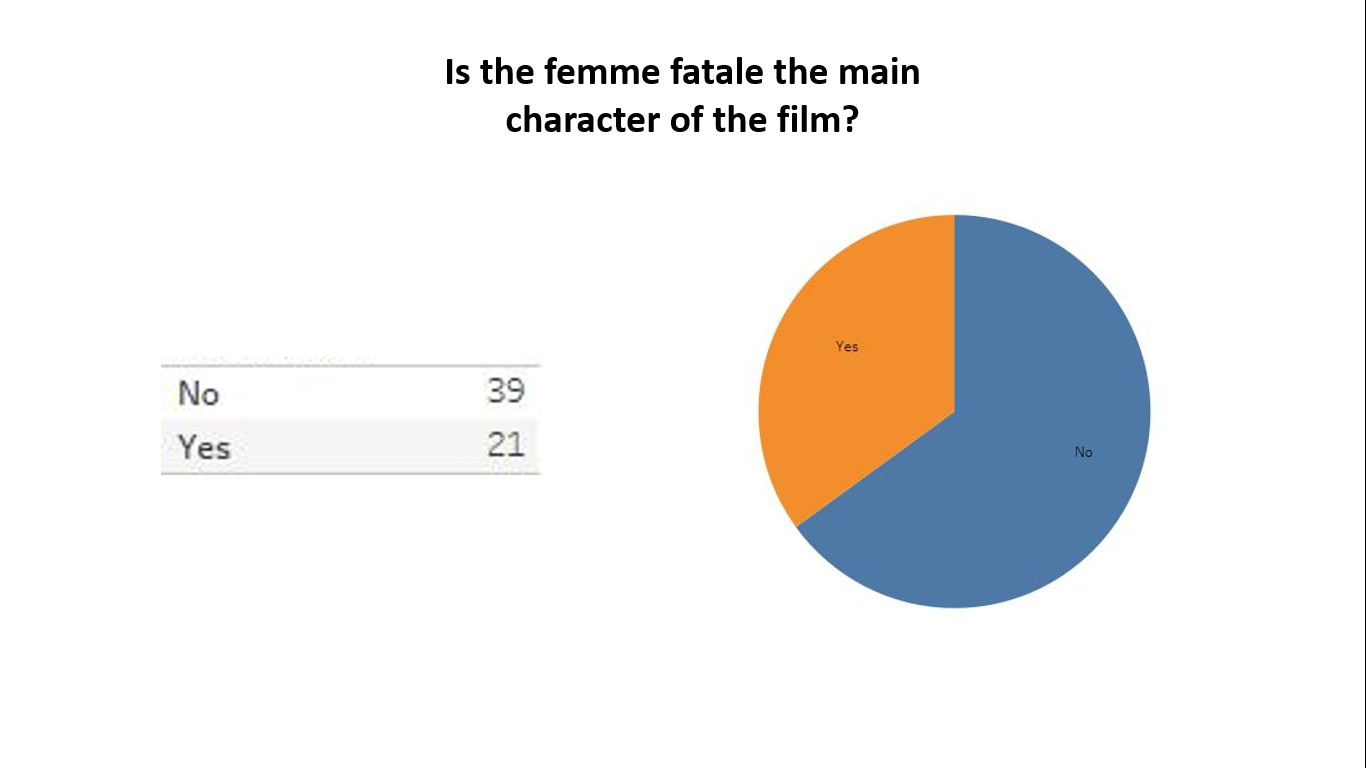

I have included this aspect of my data in order to show the representation criminal women get in these films in general. Even though these films have criminal women as characters in the stories, and the plots of many of these films are driven by these criminal femme fatales, most of these women are not the main characters of these films. I argue that this is indicative of the marginalization of criminal women in society. Throughout this project I have shown that the population of women in the US criminal justice system has increased since the 1970s. Despite this increase, the criminal justice system still centers around men as the system was built primarily with men in mind. It seems as though this increase of women’s involvement in the criminal justice system has been a silent one. This is represented in film as many of these femme fatales are not the main characters of these films but are still presented to viewers as a form of entertainment.

In conclusion, I believe that this data shows that these American films do not accurately portray criminal women. From a purely statistical point of view, the crimes committed by these women are not reflective of the crimes that most women are charged with. The methods used by these femme fatales to commit crime mainly serve to portray these women as sexual and manipulative, and their motivations to commit crime do not reflect the reality of gendered pathways to crime or identify how abuse, trauma and vulnerability plays into a woman’s involvement in crime. Most of the repercussions suffered by these women serve to either legitimize the woman’s ‘evilness’ (death, or negative repercussion), or to show how the woman can ‘get away’ with her crime (positive repercussion or no repercussion.) Less than 20% of these women suffered a repercussion that involved law enforcement. Ninety-five percent of these women were white despite the fact that the criminal justice system disproportionately affects women of color. Further, there were no black women who played femme fatales in these films. Finally, despite the fact that the population of women in the US criminal justice system is increasing, the majority of these femme fatales were not the main characters of thee films, thus symbolizing the marginalized position criminal women hold in society.

Ultimately, these films do not present criminal women in attempt to explore their real lives, experiences and oppression, but instead as a, largely sexualized, form of entertainment. These films therefore distort the reality of female criminality and women’s involvement in the US criminal justice system.

On the next five pages I have explored five of the films reported in my dataset in detail. I hope to explore the experiences and criminality of these women in context and in relation Messerschmidt’s theory of situated action. Perhaps, by doing a closer reading of some of these films, I can explore if these films in any way accurately present female criminality.