In 1971, President Richard Nixon announced his ‘War on Drugs.’ This war involved increased and harsh policies against illegal drug use and possession. These harsh policies have been cited by many scholars, notably Michelle Alexander in her book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, as one of the key causes of mass incarceration in the US.[1] Michelle Alexander, in particular, identified the horrific effect mass incarceration has had on people of color in the US. As Sara Wakefield and Christopher Uggen identified in their work “Incarceration and Stratification” in 2004, 21.6% of African American adults held a felony conviction.[2] The War on Drugs allowed for tougher crime policies in general that legitimized police authority to conduct ‘random’ stops and searches in many states, as well as introducing the three-strike rule in many states and harsh mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses.

As with many issues that affect people in our society, the problem of mass incarceration is multi-faceted. Many scholars, for instance Stephanie Covington and Barbara Bloom who created The Center for Gender and Justice, have looked at how mass incarceration has disproportionately affected women over the last few decades. Covington and Bloom argue that “inadvertently, the war on drugs became a war on women”[3] because, according to their research, women primarily become involved in the criminal justice system because of drug and property offenses. The mandatory minimum sentences introduced for drug possession and selling, and the harsher policies related to drugs in general, disproportionately affected women because drug offenses made up the bulk of offenses committed by women. Also, in accordance with Alexander’s work, these tough crime policies affected women of color.

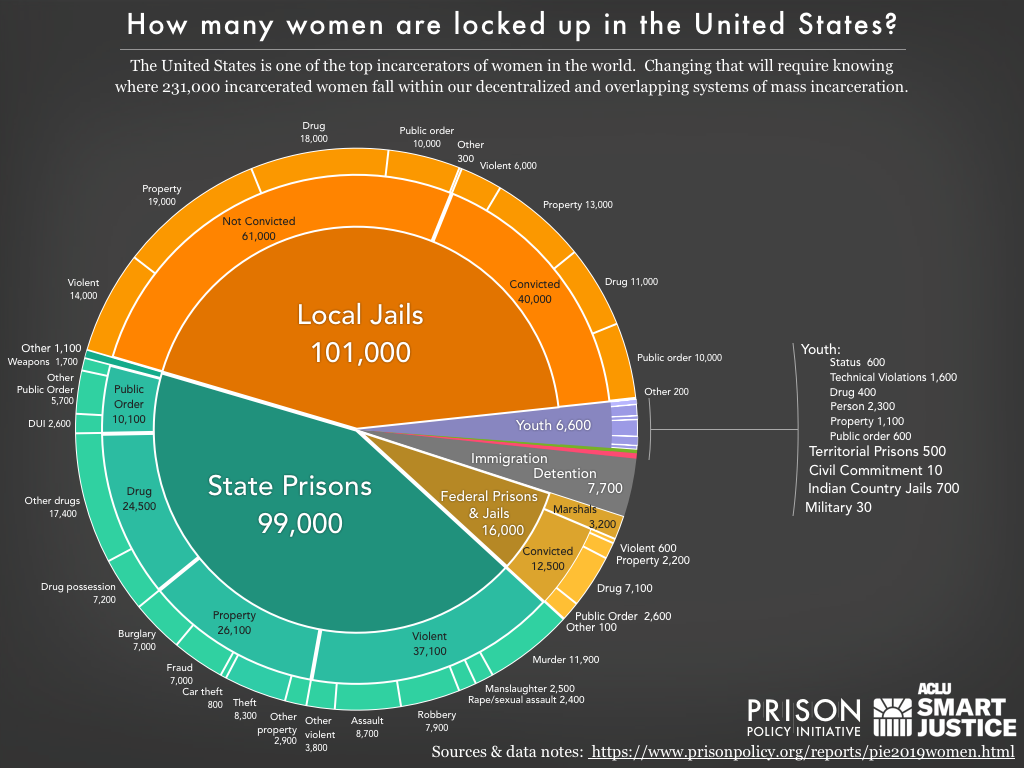

According to the Prison Policy Initiative, as of 2020 there are almost 2.3 million incarcerated people in the US. In 2017, 219,000 of these people were women and in 2019 that figure reached 231,000. The graph below shows a breakdown of the different offenses committed by these women and the different parts of the justice system they are involved in.

Scholars Erica Rojas, Laura Smith and Randolph Scott also agree that the war on drugs disproportionately affects women, because “the literature has consistently revealed that women are more likely than men to have reported drug use at the time of their offenses, to have committed crimes in order to obtain money to purchase drugs, and to have used more drugs while in prison than men.”[5] Importantly, however, the scholars also argue that the war on drugs did not just affect women, but specifically poor women and women of color. The scholars identified how the key characteristic that many incarcerated women share, is their low economic status and that the drug and property offenses these women commit are often reflective of this low economic status. As a result, Rojas, Smith and Scott argue that “for this reason, any discussion of women in the criminal justice system is largely a discussion of poor women in the criminal justice system.”[6]

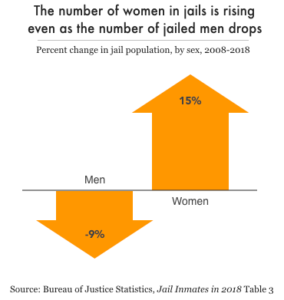

The population of incarcerated women is not only large but it is – and has been – increasing. As Covington and Bloom show, “nationally, the number of women in state and federal prisons increased nearly eightfold between 1980 and 2001, from 12,300 to 93,031.”[7] We know that this has increased over twofold between 2001 and 2019, as the female population totaled 231,000. Despite this increase, there is not necessarily an increase in female criminality. As explored above, most women are incarcerated due to non-violent drug and property offenses, and since 1998 “the proportion of women imprisoned for violent crimes has continued to decrease. The rate at which women commit murder has been declining since 1980, and the per capita rate of murders committed by women in 1998 was the lowest recorded since 1976.”[8] All of this information points to the fact that women are not becoming ‘more’ criminal, but more women are being incarcerated because of the change in crime policy. There is also evidence that shows that not only is the female population increasing, but the male population is decreasing. The prison policy initiative identified that from 2008-2018, the number of men in jails decreased by 9% and the number of women increased by 15%.

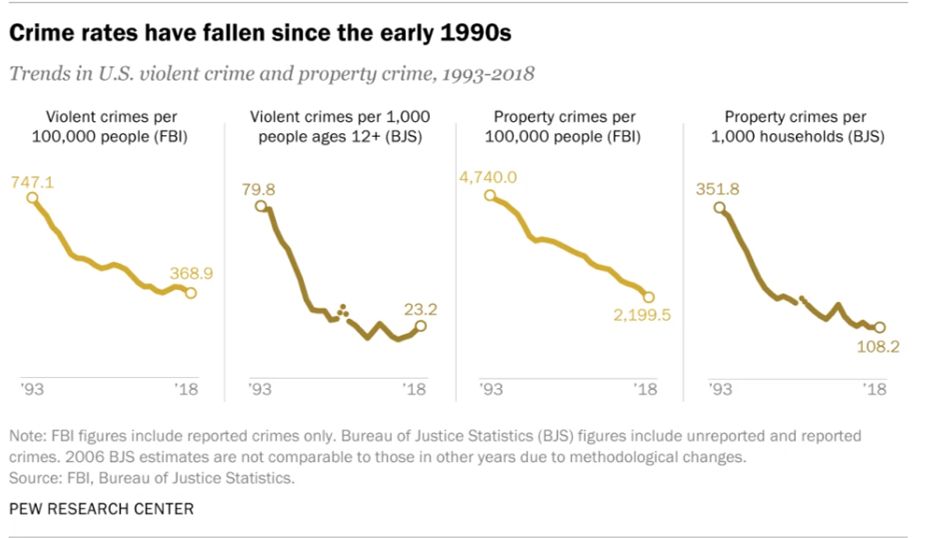

Further, not only is female crime decreasing, but research from the Pew Center of Research, which compiled statistics from the FBI and the Bureau of Justice Statistics, shows that violent and property crimes have decreased since the early 1990s.