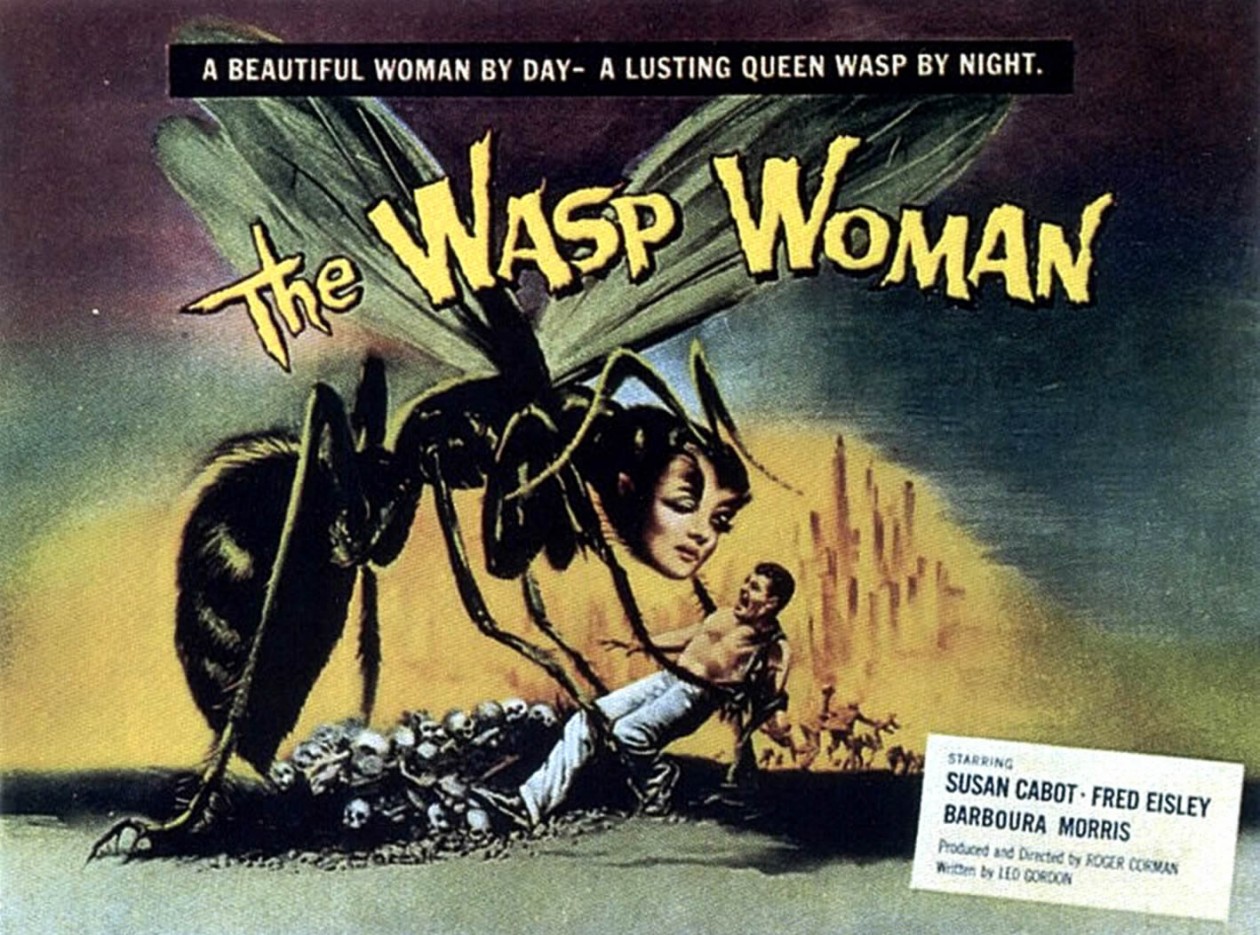

This was the Ad I was referring to in class about the sexualization of feminist. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/10/02/femvertising-advertising-empowering-women_n_5921000.html This is the article that first brought it to my attention.

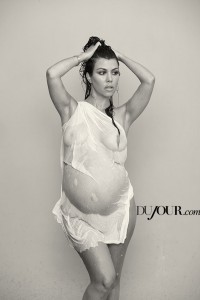

Pregnant = Sexy?

I saw this and thought it was interesting how even pregnant women are sexualized. It shows women in two very stereotypical ways; nurturing, as they are carrying their unborn child, and also seen as sexual. Kourtney Kardashian is completely naked while posing in a suggestive way. There are also examples of other celebrities posing naked and pregnant. Why can’t they be shown clothed or wearing a sports bra and jeans or something of that sort to still show off their very pregnant bellies? Any thoughts on the matter?

http://www.vh1.com/celebrity/2014-12-02/kourtney-kardashian-nude-photoshoot-dujour/?xrs=MAIN_10am

Watermelon Woman

I really enjoyed this film! I thought Cheryl Dunye was very captivating as both an actress and a filmmaker. In our class discussion we talked about the difference between the fiction aspect at the end compared to the film Daughter Rite. As upset as I was with Daughter Rite, I did not feel the same way about this film. I think that while The Watermelon Woman is not actually a real person, her story line could easily be interchanged with a real actress from that time period.

I like how the film also included parts about Cheryl’s life. The relationship between her and her bestfriend was very interesting. One thing that I’d like to touch in is some of the comments her best friend made. We always talk about in class how a woman doesn’t nee a man to be successful, or to be happy. I think sometimes this gets bogged down in only hetero relationships. I think this film shows it happens no matter what. Maybe it has to do with being a woman no matter the sexual orientation. Cheryl is constantly being set up on blind dates, and being told to find someone. Cheryl seems content with being independent. We often see this in other films too. Overall, I think it is interesting that, despite the sexual orientation, women are always being told they need a partner.

Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown

My roommate had an assignment for her Spanish class this weekend in which she came across the film, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (Almodovar, 1988). As I was doing homework next to her, I heard her shout, “Oh my god, this film is so sexist!” I looked at IMDb’s description of the film, and it seems to center around a women trying to contact a man to figure out why he has left her. I have never seen the film, but I think it would make a great addition to our class discussions. Even just the title of the film seems to be a clear indication of gender discrimination. Do you think it is ethical for directors to make such films? I think one could argue that film is art, and people should not easily take offensive to the comedic gender stereotypes that films like these play on. However, where does one draw the line? Clearly, my roommate, who is not even in this feminism and film class, noticed that this film was an ethical issue.

“Lesbian Looks” — Arzner’s Gaze

A particularly interesting idea that stuck out to me in Judith Mayne’s “Lesbian Looks” article was the representation of Dorothy Arzner and how she has been visually represented as a filmmaker. On page 164, it says, “With the possible exception of Maya Deren, Arzner is more frequently represented visually than any other woman director central to contemporary feminist discussions of film. And unlike Deren, who appeared extensively in her own films, Arzner does not have the reputation of being a particularly self-promoting visible, or out (in several senses of the term) woman director.” Further, Mayne says “..she is shown with other women, usually actresses, most of whom are emphatically ‘feminine,’ creating a striking contrast indeed.”

She goes on to discuss Arzner on the cover of the British Film Institute collection. She is shown sitting directorially next to a camera and another man, and they are both looking on to two young women who are being filmed. I thought this was a very interesting idea, because visually, the photograph is implying the notion that as a woman, Arzner is in the male position in terms of the male gaze. Since she is more “masculine” than what is considered “normal” for a woman, she is displayed as more of a male figure than a female figure. Even further, as she is the one shooting, this determines her position of power over these women. The article continues, “Arzner’s look has quite another function, however, one that has received very little critical attention, and that is to decenter the man’s look and eroticize the exchange of looks between the two women.”

I found this point very interesting because this “decentering” of the male gaze very seldom happens; furthermore, the fact that it is done by a homosexual woman almost challenges the power that the man has. It’s interesting to analyze this example that Mayne uses in the article because for once, it is not an image that has been “constructed” and purposefully positioned, as films so often are. It is simply a photograph of a live action, which makes it even more intriguing. This article was difficult to comprehend at times, but this section was a particularly useful take on the representation of homosexual–and more specifically, lesbian– discourse in Hollywood narratives.

‘lesbian looks’ response

I appreciated Judith Mayne’s point in her article when she said that portrayals of gay or lesbian personas in film usually find a way to fall back into the heteronormative formula. One of my favorite quotes was when she said, “The evidence of lesbianism notwithstanding, feminist critics would speak, rather, through a heterosexual master code, where any and all combinations of ‘masculinity,’ from the male gaze to Arzner’s clothing, and ‘femininity,’ from conventional objectification of the female body to the female objects of Arzner’s gaze, result in a narrative and visual structure indistinguishable from the dominant Hollywood model.”

The article references Dorothy Arzner as one of the few women directors who was successful in Hollywood, particularly during the studio years, and still managed to make films that disturbed the conventions of Hollywood narrative. However, none of the feminist critics who analyze Arzner’s work have discussed her lesbianism or her lesbian persona. No one acknowledges that sexual preference might have something to do with how her films function, particularly concerning the “discourse of the woman” and female communities, or that the contours of female authorship in her films might be defined in lesbian terms.

The article questions why feminist film theorists are so drawn to the “dykey” image, yet so reluctant to utter the word, “lesbian.” Mayne suggests that these theorists want the films to stand on their own, and to not have the maker represent the text, or the part represent the whole.

-“There is a striking division between the spectacular lesbian uses to which single, isolated images may be applied and the narratives of classical Hollywood films, which seam to deaden any such possibilities.”

Lesbian Looks: Dorothy Arzner

A lot of the content in this article have been issues surrounding our film analyses throughout the semester. Such as subversive text and lesbian eroticism in film narrative. Briefly we have touched upon that one scene from Morocco where Marlene Dietrich kissed a woman while dressed in masculine attire. It seems that now that this is being brought up again, we as a class, have a better understanding of the importance to these lesbian narratives in film. In a way, our course material is coming full circle. Not only do we recognize that women are represented in film, but we also understand the triumph and tribulation of getting women to be represented in film (and also behind the camera).

This brings me to my next point about the issues surrounding Dorothy Arzner as a prominent film director of the 30s/40s era. Not only is she a female director, but also she identifies as a lesbian. By the way, both identities are problematic for this time period. It seems at times during this article that the criticisms of Arzner’s films were only significant because of her sexual identification.

It seems that maybe Arzner’s work was being obsessed only because she was a female with a full mannish appearance. At a time like this, such an appearance deviates from what is normal. Sequentially, her films fell under much more scrutiny because of her sexual identity and clothing choice. I wonder if others also felt that while reading this article there was much attention brought to the fact that she wore what is traditionally masculine attire.

Netflix

So inspired by our discussion today, I visited Netflix. Interestingly enough under the “gay and lesbian” section they only have 25 films, 20 of which include naked bodies or sexually suggestive cover art. Also, the only evidence of ethnic minorities exist in group shots, no leading roles here.

Even more telling is that films like “Brokeback Mountain and “Boys Don’t Cry” aren’t even featured in this section even though Netflix carries these films! Thoughts?

The Normal Barbie

I remember hearing about an artist, Nickolay Lamm, who was getting a lot of attention for bringing to light the discrepancies between Barbie dolls’ dimensions and those of normal (and healthy) young women. Today, I learned that his crowdfund mission was a success, and he’s created this awesome new doll, Lammily, whose proportions are those of an average 19 year old American girl.

Here’s a video highlighting the difference between Lammily and traditional Barbie dolls:

I think this is a really neat idea, and is something that seems so minor and simple but could make a big difference. He’s releasing the dolls, and included a sticker pack so you can give her acne, scars, cellulite – all things that real people experience but are glossed over. Lamm said that he’s going to release more dolls of different ethnicities and body shapes too.

Lamm also released this video of kids reacting to playing with her, and it’s pretty amazing. The kids noticed the difference between her and other dolls they usually play with, and so many commented that she looked like someone they knew.

Representation in The Watermelon Woman

http://www.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9C04E2DD1430F936A35750C0A961958260

Intrigued after realizing that this was in a mock documentary I was taken for a loop by the presence of Camile Paglia, an outspoken character we’ve seen interviewed before. Her presence then lead me to question how scripted was her part in the film. The article above confirms that it was indeed just a “self-parodying cameo” but still– she was pretty unbelievable.

Overall, the Cheryl Dunye’s decision to “create” a historically powerful figure worked to her advantage. Yes, there are absolute cons to this approach: people won’t believe it, some could take offense to the fiction, people would dismiss it once they knew it wasn’t a documented history and there are probably more. But what she was able to accomplish with this approach is a fair trade off. With this generated figure, she was able to compassionately control the situation to identify social issues with race, sexuality and women (three incredibly complex topics). Choosing to make the character being sought an African American woman in an undiscovered relationship with a privileged white woman in the 30’s, nonetheless, provides a huge ground to explore. The intersections that surfaced throughout her journey to find the Watermelon Woman I believe was the intent of the movie. To follow a similarly placed film maker, (Cheryl in comparison to the white director Martha Page), we see the journey of Dunye basically searching for the actress, Fae Richards, as if trying to reimagine how Page would’ve went about in casting her.

Dunye faces a lack of interest from the world she is trying to dig answers from. The Library scene being something you’d expect (disturbing thing to expect) there was no information on these groundbreaking individuals, just unimpressed stares and shrugs of not knowing. If the story of Fae and Martha were true I feel the couple would’ve faced the same reactions of “what are you doing?/Why do you care?”.

That was a bit of a hypothesis behind the inner thinkings of the story Dunye fabricated but again the complex dynamic she framed, the interracial 30’s relationship next to her own interracial relationship, was something incredibly clever and to me went unnoticed until I thought further about the film. This provides an immediate comparison for the audience and gives Dunye further control in how her story will reflect her message. The message ultimately being see history for what it was during the social constructs of the 30’s through the 90’s and now let’s record the history we want generations after us to study and see.