The readings we got for the weekend were very interesting to me because they talked in depth about female actresses in the media. In “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” by Laura Mulvey, one of the main points she made was that women are to be “looked at” while men doing the “looking”. Although she makes the assumption that the audience of these movies consist of predominantly heterosexual males, I thought back to one of my previous film classes where we listened to the song “Bitch Bad” by Lupe Fiasco. Mulvey states that many males viewers of the movie identify with the main hero of the film and so view the co-starring actress through the hero’s eyes. In many cases this behavior translates into reality, yet does a similar behavior exist in women? Like the song states, there are many females who may watch the same films and identify with the female characters. Most times both genders have been socialized to associate certain parts of the female body with sexual activity and nothing more. They are also being told what images are “beautiful” and what are distasteful.

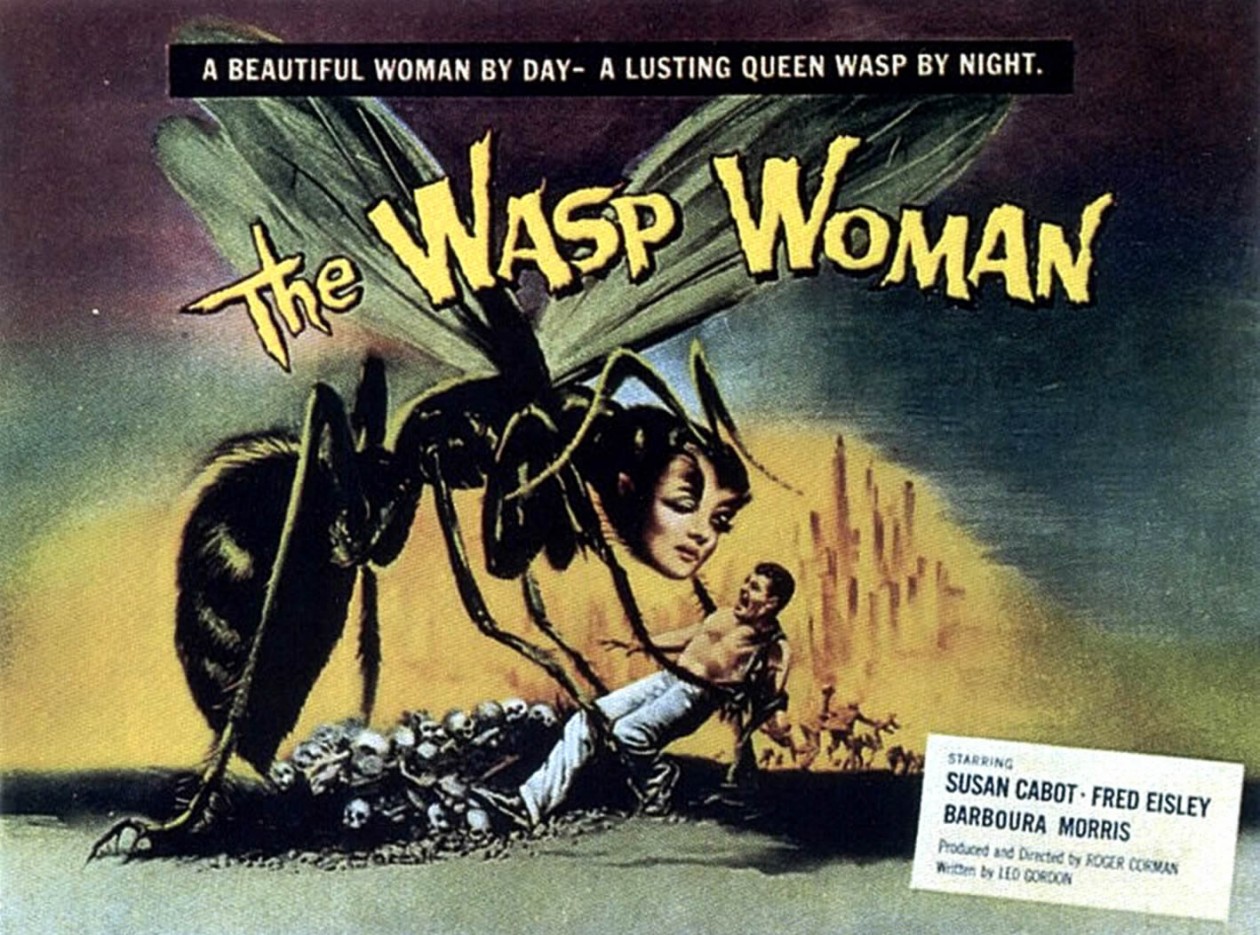

Johnston goes into the topic of objectification of women and socializations as well. Johnston credits the term “iconography” as being partly responsible for the stereotypes placed on women in the media. In the past and in present day as well, women are filmed in different ways than male actors in a movie. I find myself getting bored with females in action movies because I know that they simply exist in the movie to as a causality, and for the inevitable sex scene. For almost all other scenes in the movie, she is not important. And in both of these scenes as well, the main hero is involved and is also the one in charge.

Johnston believes that all decisions in film have been made intentionally. A blonde actor is chosen, and the light hits her hair every time she is present in the movie. She is naive and innocent, or a damsel that must be protected. There are many examples of decisions filmmakers have made in order to portray women in a certain light. As both authors have pointed out, women in a movie are almost always connected to a male figure. In class Professor Sikand posed the question “Is it possible to make a feminist film?” I think it will be very difficult to do so because you would have to be very aware of the decisions you are making in terms of visual and narrative. And after all of that work, would anyone watch it? A phrase I’ve heard a lot is “Sex sells.” and this is very true in the media world today. But is it really that impossible to make a very interesting action movie without a sex scene?

Question

One of the points that I was a little confused by was Mulvey’s use of terms such as “castration” and “phallus”. I know the definitions of these terms however, she refers to the woman with some of these terms. In class Professor spoke about the lack of a penis being connected to the reason why men are more dominant than women. I found the following line thought provoking:

“…it is her lack that produces the phallus as a symbolic presence, it is her desire to make good the lack that the phallus signifies.” (1st pg)

Do you agree with this quote? Is it possible to make a feminist film without addressing this?