The first part of this blog post will be a brief summary of Women’s Cinema as Counter-Cinema for today’s class. In case you missed some of the important ideas of the article here they are.

Most importantly, you should understand the following ideas: Myths, Iconography, signs, stereotypes, counter cinema, and the difference between idealism and realism and how that is important to the construction of the film.

The most important quote from the reading is, “There is no such thing as unmanipulated writing.” (page 28) I felt that this is the core to the argument in Johnston’s article. I thought that the discussion about myths and the malleability of their signs provided a good backbone to this statement. To be sure you understand what a myth is, I would look on page 22-23 to better understand this concept.

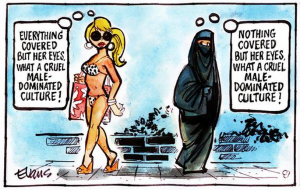

In short, myths and the sign system that they are based on are highly malleable. Although you might think that one sign denotes something, it can easily be manipulated to refer to something else. Thus, creating a whole new denotation and altering the meaning of something that you originally found to be true. (Also worth noting, is that this concept can be applied to the conversation that we have about subversive messages)

Next point to be familiar with is, Idealism vs. Realism. Bottom line is, movies do not represent reality. Movies represent ideas. Johnston wants us to reject the sociological approach to film critique and understand that a film does not represent a culture, but is rather formed by a current cultural idea which is entirely at the scrutiny of the filmmaker at the time of production.

To connect this with the Blonde Venus, I wanted to focus more in depth on a specific passage. One quote that specifically stood out to me is (on page 30) “Any revolutionary strategy must challenge the depiction of reality; it is not enough to discuss the oppression of women with the text of the film; the language of the cinema/the depiction of reality must also be interrogated.” My original question is, how do we see this in Blonde Venus, and consequently, how do we respond to this? However, I think that this statement is particularly interesting because it started to make us think about feminist films and if they are even possible to make. How do we respond to the context of which a film is made when we aren’t in the era that this film is made.

I thought that the discussion that we had in class was really interesting. One point that was brought up was the fact this film was made in 1932. We can all agree that a lot has changed since this point in film history. To better understand the cultural context of this film we need to understand the process in which the film was made. We noted that at this time the hayes code, the male director, and the sexist ideologies were all contributors to that culture at that point in time. I think that without those factors we can’t necessarily decide what this film is trying to say about women. I won’t elaborate on what I think this film is trying to say, but I can comment on the fact that I don’t think that it’s as easy as I thought to determine the meaning of this film after reading Johnston’s article.

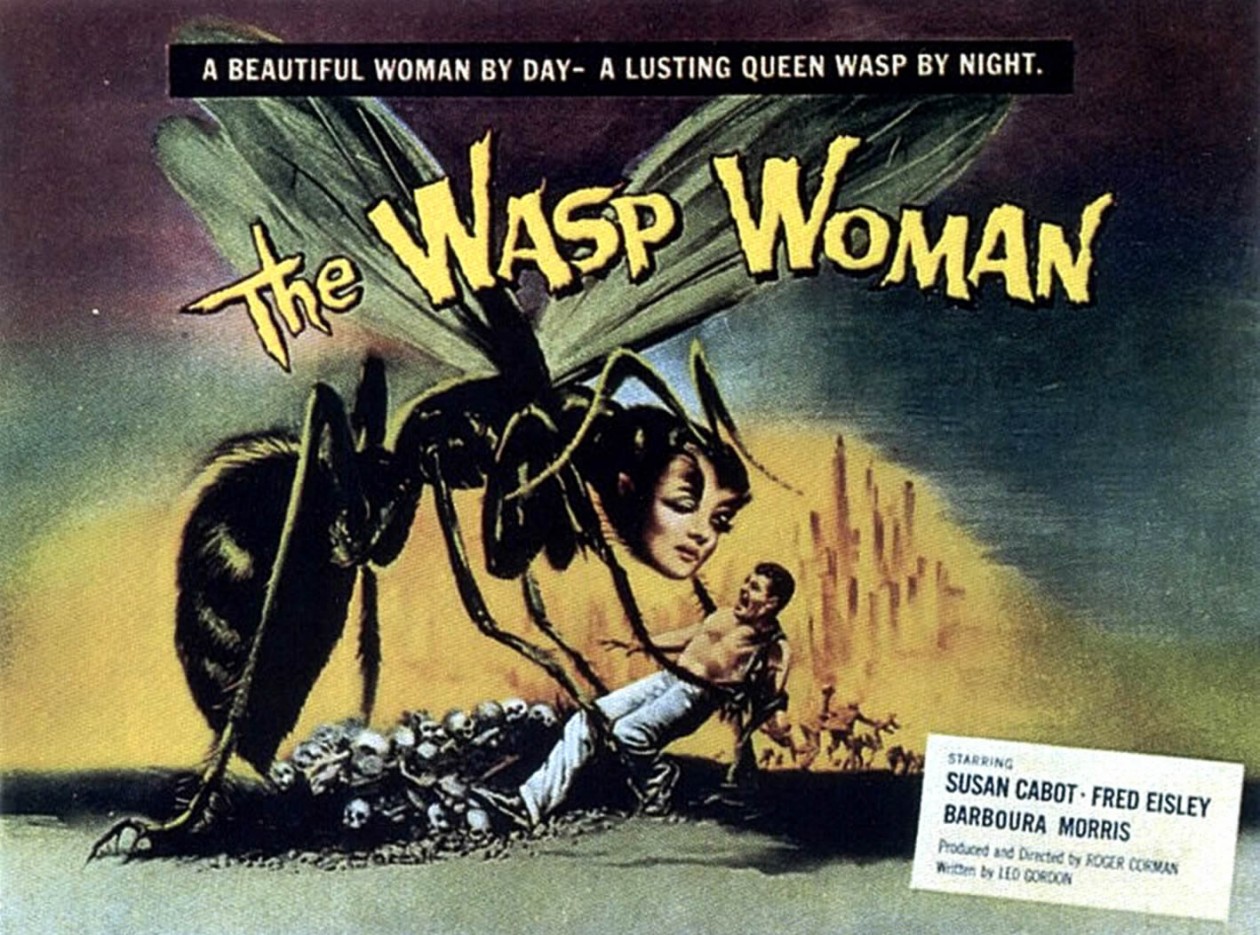

I think just the fact that we are unsure about what this film is proves Johnston’s original argument. That is, films are based on ideas not reality. More specifically, films are based on the ideas of the filmmaker who is constructing that film. For that reason, can we ever really be sure what the director was intending for us, since we don’t necessarily know what he had in mind. However, Johnston gives us a lesson in iconography in order to apply this to the films we watch. That brings me to this next quote, (on page 29) “Clearly, if we accept that cinema involves the production of signs, the idea of non-intervention is pure mystification. The sign is always a product.” I think that if we are to use this idea of iconography in the films we watch then we can better understand the way in which these films were intended to be seen.

So, before I end, in regards to the original question that I address in the title, I would like to hear more comments on this. Can we have a feminist film? Like I mentioned in class, I do think it is possible, given that what Johnston said about films being about ideologies as opposed to reality. So if feminism is an ideology then it should be possible for a film to be of a feminist nature. The problem remains that regardless of any director’s intention the problem remains with the audience. The audience is, in most situations, oblivious to certain cultural issues and for that reason the meaning of the film could be lost or misinterpreted. So how do we overcome this, and that being said, is that even possible?