I went to see the Daily Show!!

At the early hour of 11:00 a.m I awoke, showered, and joined the Wooten family for a train ride out of Metro Park into New York City. I wore two pairs of pants, tall boots, a thermal shirt, my winter jacket, a woolen cap, and gloves. Even with all that paraphernalia, the cold was biting and I constantly tried to cover my frigid lips and neck with the top of my jacket. Taking off one glove for just a brief second left my fingers numb even when shoved back inside my glove. My boots, worn in anticipation of snowfall, bit at my ankles and left my feet raw by the end of the day.

After a brief wait in line, the staff shepherded us into the studio, where the famed desk of John Stewart sat dead center in flurry of monitors, cameras, microphones and lights. The lady in charge of seating the audience in an orderly fashion came out when we were all seated and spoke to us. She wore jeans torn at the knee and a bulky red jacket.

“Normally by now you’d all have had a chance to go the bathroom . . . but we tried to get you inside as fast as we could because it’s fucking cold out there.” Then over the loudspeaker, Samantha Bee reminded us to turn off our cellphones and, if we were from 1987, our pagers. The monitors told us to turn off our own phones before assisting the elderly in turning off theirs. People seated around us joked about their favorite episodes, and about poker and smartphones and heckled each other.

A warm-up guy came out who made us shout and clap a whole bunch and chant for Jon, then we had to shout and clap more and shout and clap more and shout and clap again and then chant for Jon again and then shout and clap. My voice was sore.

“This lady’s been drinking,” he said to one woman who had shouted a lot, and was very enthusiastic. We were all so riled up that we couldn’t help but laugh. He called another a Jewish farmer. Then we shouted and clapped and laughed and chanted for john and clapped and he finally brought the guy out, Jon Stewart himself, all five foot six of him, and Jon Stewart was a riot. People fired Q&A at him:

“Are you upset over the packer’s loss?”

“I’m torn up over it. I had to tell my kids to put their cheese-heads away and go to bed.”

The air was electric. Every question fired, he shot a joke right back, something clever and cutting, like a knife.

“Medical Marijuana in New York?”

“Uh, yes I guess? Because I have a headache?”

We were doubling over in our seats. The mics were picking it up perfectly clear.

“What’s it like making a movie, Where’s the premier of your movie, and are we invited?”

“It’s a real touching true story – not without it’s artistic license of course, Shaq’s in this, and he plays a Geenie, but still . . .”

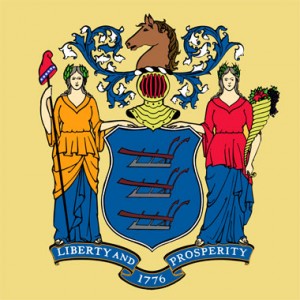

And then the show started and we stomped and clapped for him and laughed like high hell, and he made fun of corruption in New Jersey and pointed out the severed horse head that is a part of our state flag and my body shook and my smile widened. For all the time and effort and train rides and waiting and cold it took, it happened in a flash, like a brilliant, bright spark of electricity arcing off of a giant cold circuit breaker, but the spark was so bright and hot that it warmed up my cold, cold bones. And then, just like a spark, it was over, and we were out again in the blackness of the New York City streets, hailing a cab and descending into the subway.

I got home, removed my boots, and rubbed the puffy white blisters all over my toes and the ball of my foot. I hobbled over to the couch and collapsed, exhausted.

Worth it.