Just thought I’d share a picture of Martha’s memorial still in Cincinnati’s Zoo. I highly doubt Martha looked nearly this happy.

Category: Uncategorized (Page 2 of 11)

With the discussion of de-extinction of the passenger pigeon, I thought this was an interesting and related video of how the reincorporation of a species can change the environment around it in such drastic ways. By reincorporating the passenger pigeon into nature, many different considerations have to be taken on how the integration of this animal into the wild will affect the environment and social construction (such as the food chain and habitat location) of nature. The passenger pigeon could force other animals out of the niches they currently hold, which could cause either a positive or negative affect on the environment (such as the incorporation of invasive species). It is a very interesting topic to consider.

The video I chose depicts a group of children at Yellowstone National Park approaching far too close to a wild bison bull with the encouragement of an adult filming the events (hereafter referred to as “Moron”), and then running for their lives when the bison – entirely predictably – charges them. This human-animal interaction illustrates the dangers of substituting voyeuristic thrill for respect for an animal.

The very first thing we hear in the video is Moron assuring the children that “he’s friendly” (B Loy). Rather than shepherding the children away from the beast that has greater strength and weight than all of them combined, Moron just stands back and films the children as they approach the bison while repeatedly exclaiming “oh my gosh” (B Loy).

As the children approach, the bison turns to face them and begins shaking its head and hind quarters about while snorting loudly: classic warning signs that it is preparing to charge. Moron even notices these “gestures,” (B Loy), although he doesn’t take any action to mitigate the considerable danger facing the children; whether this is because he didn’t realize what the gestures meant or because he was simply too empty-headed to act is unclear but given what we’ve seen of him so far, either is possible. The bison then moves to block the path it saw the children taking; because it stands its ground as the humans approach and even moves to block their path, this is clearly territorial behavior and not self-preservation instincts.

Which is bad.

As the children continue advancing, the bison’s warning gestures become more pronounced and it lowers its head – this bull is going to charge whatever draws its attention next. The two children who had managed to get past the bison are saved from almost certain death by a man who quickly hops onto the wooden footpath on the other side of the bison, the sudden motion causing it to charge. The main group of tourists flees away from the bison’s territory, but one child breaks from the group and runs parallel to the border; the animal singles this child out and pursues him, quickly closing the distance until the child turns and sprints away from the bison’s territory with less than a yard between him and the animal, at which point the bison, satisfied that it has made its point, abandons the chase (B Loy).

It is by sheer luck that nobody was killed in this incident; it’s hardly uncommon to hear about tourists gored or trampled by bison, almost universally killing the tourist. The worst part about this kind of thing is that it’s a 100% completely avoidable situation; even a modicum of common sense would have defused the situation before it escalated to the point that it did. It was by sheer luck that nobody was killed, and if it were to happen again fatalities would be almost guaranteed. It’s truly infuriating that nobody had that little bit of common sense not to approach Nature’s Rage-Filled Battering Ram.

Well, we’re calling the camera guy Moron for a reason.

Since I grew up on a farm that counted several heads of bison among its livestock (the bison were there before we were), I’m more familiar with the temperament and physical capabilities of bison than your average person idiot dad on vacation. This is why I find it simply infuriating seeing things like this charge happen. Not only does this sort of behavior jeopardize the safety of the tourists but it also epitomizes the marginalization of both the animal itself as it is reduced to a check box on the family’s vacation summary as well as its “wild-ness” as the people in the video treat it like it is a tourist attraction there solely for their amusement.

Bison are not animals to be trifled with; they can weigh to 2,000 pounds (read: a lot bigger than a person), run at up to 30 miles per hour (read: a lot faster than a person), jump up to six feet vertically (read: a lot higher than a person), and their heads sport two long, sharp horns sprouting from a bone plate in the skull that they can use to smash through a reinforced fence (read: a bison will ruin your day). Furthermore, bison are typically ill-tempered and remarkably unintelligent animals with highly aggressive and territorial dispositions, and will not hesitate to use the aforementioned physical abilities to run down and kill anything that threatens it or intrudes on their turf. As seen in the video, that includes tourists small children with questionable adult supervision. Long story short, despite being herbivores a bison can and will mess you up if you don’t treat it with caution and respect.

The group’s close approach to the bison also encroaches on its “wild-ness” as an animal and reduces it to a sideshow stop on Yuppie Dad’s Great Yellowstone Vacation Plan (patent pending). The father displays several behaviors that Malamud condemns, such as engaging in the voyeuristic thrill of watching the bison from a, at least in theory, superior vantage point of greater power (Malamud 221). While he (thankfully) doesn’t take it as far as the physical self-stimulation Nimier witnessed (qtd. in Malamud 220), Moron does take part in the all-too-common metaphorically masturbatory exercise of wrapping oneself in warm, fuzzy feelings of superiority while sipping on a hot mug of smugness and looking at the “inferior” animals of the wild. In the eyes of the tourists in the video, the bison was not a living, breathing creature but a tourism draw like Old Faithful (note: at no point has a geyser ever tried to violently kill somebody).

By reducing the bison to nothing more than a spectacle to provide fleeting amusement on vacation, the animal that was once revered as a sacred creature by the Plains Indians is marginalized until it is nothing more than a silhouette on the souvenir T-shirt your 15-year old son wears to let all his friends know about his awesome summer vacation. The bison has been marginalized to something that is only good to look at for a few minutes by the side of a road; the animal that once owned the Great Plains has been reduced to Yellowstone National Park’s Bison™, merely a mascot for a tract of land in Wyoming and Montana – or for a certain clearly inferior liberal arts college that shall remain nameless (looking at you, Chris). In the popular opinion, bison are simply objects for humans to look at in mild-to-moderate wonder; few people particularly care if the bison is looking back. Berger identified this imbalance in Why Look at Animals?: “animals are always the observed. The fact that they can observe us has lost all significance” (Berger 16). Humans are too wrapped up in looking at the bison from the windows of their Winnebagos to bother wondering if the bison is looking back, and what it might think of them.

By forgetting that bison are more than source material for screen-printed images on T-shirts, they marginalize the animal until they also forget the sheer strength and lethality it carries. This marginalization is the result of the reduction of the bison to a mascot or a tourist attraction, and stems from Man’s tendency to look down on animals who do not resemble himself. However, the human perception of the bison, no matter how erroneous, cannot change simple facts such as this:

Those kids are damn lucky.

Works Cited:

B Loy. “Angry bison charges small child at Yellowstone in scary video.” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 5 Sep. 2012. Web. 9 Nov. 2014.

Berger, John. Why Look at Animals?. New York: Vintage International. 1977. Print.

Malamud, Randy. “Zoo Spectatorship.” The Animals Reader. Ed. Linda Kalof and Amy Fitzgerald. New York: Oxford Press. Print.

If there is one relationship with animals I have always loved, it is that between man and falcon. The relationship is very stoic compared to some; one in which the man responsible for the falcon simply releases the bird and watches it soar around before ultimately laying waste to a small animal or bird. This is exactly what a falcon would do normally, just in this case it is brought to the hunting ground by a human being, follows some of his calls, and does not reap the full benefits of its kill.

The video I watched was exactly this relationship on screen. Several men go to a large field, one walks out with a falcon, removes its head cover and simply watches it do its thing. The camera man shows the hunter fitting himself with a orange hunting coat, an action which screams “things are getting serious.” The video is embellished by a very loud, intense choice of music. The camera angles and movements are also very dramatic, choosing to highlight scenes with lots of action and employ slow, daunting pans when there isn’t too much going on. There is this overwhelming sense of preparation for a big event, almost comically so, as we get ready to watch this beautiful bird go out and kill something. Low angles on the male hunter give him a sense of power and purpose in the shot, preparing us for this massive hunting escapade. And then, all at once, he releases the bird, and further the actions of the man are dramatized, switching between close ups on his face and wide shots of him moving around the ground and peering into the sky, watching his beautiful bird begin the hunt.

What’s funny to me about this video is that there is so much focus on the hunter, it’s easy to forget that the bird is doing literally all the hunting. Sure, there is some training that can be applied to a bird to make it do your bidding, and there are plenty of videos all over YouTube on the art of falconry (which are awesome and I recommend looking into them), but ultimately the experience that the hunter is getting from watching the bird hunt is a similar sort of voyeurism that Malamud talks about in his analysis of zoo spectatorship. To be so close to this magnificent bird while it hunts is simply to live vicariously through its actions, not to have any actual ownership of the kill. And I will admit, even though I understand that the fun comes in being so close and yet so far from death, I still enjoy the hell out of it. Watching a bird hunt is one of the most gorgeous and terrifying things I’ve ever seen. You can watch the falcon lock on to its target a little later on in the video, swooping in at a dazzling speed to overwhelm the helpless duck from above and send it sprawling to the earth. The raptor then swoops down to the site of the wounded duck and literally squeezes the life out of it with its razor sharp talons in an emphatic yet calm way. The duck’s death is cold and remorseless – just another bird broken by the hunting dominance of the peregrine falcon.

I’m being pretty bold in calling one’s observation of the hunt voyeuristic, especially given that Malamud himself is talking about more of a sick, masturbatory pleasure from watching animals do things in confined spaces. But I believe that in videos such as this in which a bird is being used for both intrinsic and instrumental purposes, there is a certain form of arousal, one that comes from witnessing a murder of some sort. We call a human killing a human murder, and we call a falcon killing a duck “awesome.” Is it so ridiculous to think that there is a vicarious pleasure to be had from watching a bird commit a crime against another bird that we could never commit against another human? I think videos like this are posted to satisfy the guilty pleasures of those who want to observe death from a comfortable distance, watching the subservient bird do the deadliest deed with no regrets. The falcon is an ice cold killer, and maybe that’s exactly what the hunter and the viewer wishes he could be for those four minutes.

We as humans have spread our influence to just about every corner of the world, regardless of the implications. The Kruger National Park in Africa is 19,633 square miles, containing 350 black and roughly 8,500 white rhinoceros. Armoured skin, a fierce horn and weighing as much as a car, a rhino is an animal you may never see in the wild unless you seek it out. The sheer size of a rhino along with it’s signature horn make it almost prehistoric, and as a result, not fully understood. The video is short in length, totalling only forty seconds. Within that short time frame we see an intruder and the resulting reaction of the rhino trying to protect itself. The car halts as a rhino appears, as it slowly moves towards the vehicle. It’s worth noting that at around :13 seconds, the rhino makes a charging gesture, as a warning of it’s intentions.

The man in the car that recorded the video seems to be both unaware, and poorly educated about rhino behavior, and attempts to calm the animal by saying “Easy! No! Easy now easy!” This attempt to get through to the animal is futile and representative of a misconception, our domesticated approach and attitude towards animals isn’t universally applicable. In more common terms, how we treat our dog and cat shouldn’t be projected upon a wild rhino. It’s a poorly understood natural world outside of our cushy lives, but it still abides to laws of nature and it’s rules. Nature preserves are examples of what I consider to be glorified zoos, due to the both the sparse human interaction, along with our evident presence. A rhino charging your car will not be stopped by a simple request, but is based on the idea of domestication and it’s consequences. The interaction in this video is short and poorly represents a false ideology of our relationship with the natural world, especially when uneducated. An unrelated but relevant point is even the format of the video attempts to label the animal as dangerous, when in reality it was responding to a threat in it’s own domain. The word CHARGES in the title is capitalized in an attempt to label the rhino as dangerous.

“The spectator’s position is circumscribed by paradox: the zoo promises it will allow them to see everything, but they really are seeing nothing.” This quote from Zoo Spectatorship demonstrates the paradox with our influence in our natural world. The idea of a zoo denies animals their defining qualities, such as a cheetah’s speed to hunt the impala, or the rhino’s horn to protect it’s family and charge through predators. We often become spectators for human enforced entertainment, following Malamud’s idea of voyeurism. Humans as spectators enforce the idea that humans are superior, along with enforcing low interaction animal relationships. Voyeurism is defined by Malamud best through the following quote, “The voyeur seeks a spectacle, the revelation of the object of his interest, that something or someone should be open to his inspection and contemplation; but no reciprocal revelation or openness is conceded” (Malamud 230). Another paradox is as follows: how do we, in a continually intertwined world, influence and remain present in nature in a mutually beneficial manner. Are we supposed to totally remove ourselves and let natural selection persist, or rather control the entire entity that is nature? Nature preserves are examples of conservative approaches towards our relationships with animals. They are human influenced, but nature focused, limiting out interaction. The focus of these preserves are to protect the biodiversity, and are non for profit. The nature focus and no profit definitely are better than a zoo, but still raise moral issues.

Many of these thoughts draw from a similar starting question, are we able to have genuine, and mutually recognized interactions with wild animals, and if so, why? Malamud raises the issue of animals and their media portrayals, which aid in developing a poor identity for wild animals. He argues that media often uses animals due to their inherent relatability, and our perceived mutual interaction. Drawing off a previous point, the title of this video is capitalized and formatted in such a way to draw our attention, but it demonstrates a stupid human overstepping his boundaries. The truth is, the rhino clearly was both defending itself from a foreign object, along with protecting it’s home regardless of the title of the video. This video raises a final issue at the end with the slogan, SHOOT, SHARE, SELL. This simple alliteration forces the animal into being a commodity, a forced instrumental view, which neglects looking at the rhino through an intrinsic lens.

Works Cited:

Malamud, Randy. Zoo Spectatorship. New York: New York University Press, 1998. Print.

“Petting a Tiger Shark” is one of many promotional videos for the GoPro camera. The video itself is only about 1:45 seconds long, but it contains many examples of what Malamud discusses in Zoo Spectatorship. This ad depicts a professional team of divers descending into the ocean with a carton of fish and an intention to film, feed, and pet a Tiger Shark. The video starts with the focus on the divers jumping off the boat and making their way down to the ocean floor, while creepy and suspenseful, albeit dream-like, music plays off in the background. The song is San Fermin’s “Sonsick”. The music picks up when we see the first shark swimming alone on the floor, circling near the diver. The climax of the song occurs next – when the diver offers a piece of fish up to the shark, and it takes it while continuing to swim past the diver. Then, with the piece of fish still in the shark’s mouth, we see a hand come up into the frame and stroke the underbelly of the shark. The shark seems to pay little attention – continuing on with his way, but he does circle back for more food. The diver again reaches out to touch the shark, who this time immediately jerks away. Another piece of food is offered in the next shot, and then the diver continually rubs the shark’s face. Surprisingly, what happens next looks like the shark is not only complying, but at ease with the contact. This is a conflicting scene for me – it seems as though it was edited to slow down the frame, to make it seem as though the diver was petting the shark for longer than he actually was. Also, the diver has both hands holding the shark’s head, and the shark twists their body slowly upon contact and lies on the seafloor. It’s hard to tell whether or not this reaction is one of compliance, comfort, or an attempt to wiggle away from the hands of the diver. The video ends with a tight shot on the shark’s face, focusing on its’ eye, while the lyrics in the song coo: “don’t be scared” – a conscious editing decision intended to pair the suspense of the song with the mystery and intimidating attitude of the shark.

Many concepts Malamud explores in Zoo Spectatorship are present in this short video clip. The first concept is feeding animals – one that the diver in this video does multiple times. Malamud quotes Mullan and Marvin in his argument, stating: “rather than the animals needing to be fed, it is humans wanting to feed them…the humans demand to be noticed by the animals”(225). This scenario is very similar – despite the fact that the human is in the shark’s natural habitat; the shark is not in a zoo. However, this diver still wants to be noticed by the shark by feeding it, he wants to be able to pet it, touch it, connect with it…even though the shark simply grabs the fish and continues swimming, paying little attention to the diver himself. Another quote from Malamud elaborates on the dynamic between humans feeding animals, saying that “the act is generous and the pleasure is innocent, although both derive from a base of superiority and power…making another being eat out of your hand – that yields a special thrill…if it is large enough to crush us”(225). We see this same dynamic in this video clip – although the act is innocent, the diver is still in control of the situation. The shark is still wild, but a human is still imposing their presence in the animal’s natural environment, attempting to understand, be there for, and be recognized by the animal. When the diver touches the shark, attempting to pet it similarly to the way one would pet a domesticated dog, the act is definitely made out of curiosity, wonder, and possibly appreciation. However, the shark can’t but “disappoint”, as Berger discusses, because the shark’s gaze is fleeting. The shark is simply there for the food, not because the animal wants to indulge in a friendship. We see the shark jerk away from the human’s touch to his face, but the human is persistent in continuing to pet and touch the shark.

Despite these arguments against the diver, Malamud would most likely prefer this scenario over one where the shark is trapped inside a tank. The diver is only a visitor, and a generous one at that. Despite the diver indulging in a dominant behavior, possibly a “voyeuristic” behavior as Malamud discusses, the human is not caging the shark or trapping it – a positive alternative to restricting the shark to a life inside a tank.

Works Cited:

Malamud, Randy. Zoo Spectatorship. New York: New York University Press, 1998.

Nimmo, Cameron. “GoPro: Petting A Tiger Shark.” YouTube. YouTube, 12 Aug. 2014.

Web. 06 Nov. 2014.

I found this video while searching the web today. I think it applies directly with Randy Malamud’s Zoo Spectatorship. As Malamud prefers television networks with animals than the zoos, what would he say about the intentions of the Discovery Channel? I think he would be against this.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QaihEthj4qs

While searching on YouTube for wild animals, I came across this video of a human interacting with a wild Killer Whale. To be honest I did specifically type “killer whales in the wild” into the search bar, but it still counts. I couldn’t resist considering my love for the Orca species. The video, coming from YouTube, isn’t in the best quality. A simple phone camera can record videos and they are being posted on the web. In an instance where an average human being encounters and interacts with a Killer Whale, a simplistic recording device will suffice. In this video we see a human and a whale having a friendly match of tug of war with what seems to be some sort of branch or stick. Both the human and Killer Whale seem to be having a fun time as they experiment with each other, and testing their boundaries. They Killer Whale seem to be equally interested with the human, as the human is interested with the whale. We know that this is a friendly encounter between the human and Killer Whale because the proximity of the human’s hand to the Killer Whales mouth was close enough for the killer to bite off. Instead, the ginormous creature with a reputation of being ferocious (hence receiving the name “Killer Whale”) decides to gently grab hold of the stick and interact in a friendly manner. If you listen to human and killer whale are also imitating each other in the noises they make. As the human whistles at the whale, the killer whale projects his whistle, and the two try and match each other in pitch. Since this video was taken from what could be assumed average fisherman, the videography was the least of their concerns. Videoing the interaction by any means was good enough for proof of this amazing incident that had taken place. No music was added and no particular framing of the video. I will say that the person taking the video did a good job of capturing the happy look on the man’s face, as well as the playfulness of the killer whale as they interacted. There was no main point the videographer was trying to portray in this video. No changed were made by editing to makes us believe certain things. The things we see and take from this video are the true consequence of an interaction between human and an animal in the wild.

As I watched and analyzed this video I realized a couple of things. Out there in the wild, the Killer Whale and human were equals. Although humans have the capabilities to hunt and capture whales, this incident shows the true innocent and curious interaction of two species in the wild. Both the human and Killer Whale happened to find each other in the wild and we’re curious to what would happen when approaching each other. While realizing that the interactions are clearly consensual it made me relate to Randy Malamud’s essay Zoo Spectatorship. Randy Malamud commonly comments on the atrocities behind humans spectating animals in zoos, but I find it ironical that we see the animal spectating back. The Killer Whale has taken itself out of its natural course in a day to interact and view this human. We know the Killer Whale isn’t just playing, but spectating because of the Killer Whales actions. The popping up of the head, then lowering back down to view the human is a technique, used by all Killer Whales, known as “spy hopping”. I find it interesting that while Randy Malamud’s essay notes the unreciprocated look from animals, we find an instance where the look is reciprocated, and perhaps even initiated.

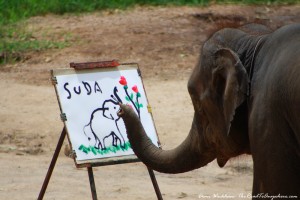

“Painting Elephant in Thailand”

This is a short montage of an elephant show in a zoo in Thailand. The first part of the video is of elephants lined up and “jamming out” to music while playing harmonicas. The music is up beat and cheery as the audience awww and cheers on the elephants. They are nodding their heads up and down and the men in the background are standing around the elephants with cattle prods or sticks of some kind, clearly this implies that this is not a natural behavior, the elephants have been trained to “enjoy” this music.

The next part of the video is a zoom in of another part of the elephant show. The music becomes very relaxing and there is a close-up of an elephant painting. The elephant, Suda, is holding the brush in her trunk. There are many videos of elephants painting on youtube and while trainers claim it is a way for the elephants to practice and demonstrate the adeptness of their trunks, generally this is also not a natural behavior.

The elephant also paints a picture of an elephant reaching for tree leaves and while this is meant to show self-awareness, it is important to the viewer to remember that this is a learned trick. It has been taught to the elephants by their trainers as an effort to entertain the crowd and gain publicity for their business. However, if one wanted to view this in a less cynical manner an argument could be made that the elephant is merely demonstrating it’s intelligence and ability to use it’s trunk. It can be viewed as a way of educating the public about the intelligence of the animal. The camera then pans over to the crowd who applauds Suda and gets up to take pictures on the other side of a railing, clearly the audience is showing

Suda is even taught to write her own name again demonstrating self awareness. But is she actually aware that this is her name and this is what she looks like? Is she expressing herself through painting? Or is she merely doing a trick taught to her to amuse the public?

Finally, there is a clip of an elephant, presumably Suda, “playing with a soccer ball.” In this clip you see the trainers fully and that they are standing with Suda as she kicks the soccer ball very far. Then as the crowd applauds, presumably Suda is given another command and she throws the ball behind her and kicks it with her back foot. Again an argument can be made that this could be an excursive for Suda, so she keeps up her agility and this is just a playful trick that she enjoys doing. However these tricks that she has been taught do demonstrate her intelligence they are not natural behaviors that an elephant would do and clearly she has been trained them through a technique of “punishment and reward” based on her performance.

Malamud author of Zoo Spectatorship argues that zoo spectatorship, like as what had happened with Suda, is not for the animal but for the humans. He even discusses how zoos express human propensity for imperialism.

Human control over zoo animals celebrates an imperial relation toward the realm of nature and its subordination to our whims. But in the long term, a human society that expresses its relationship to the natural world via the institution of zoos risks foundering amid our imperious ecological ethos (Malamud 228).

What he is saying is that human propensity for control over other beings has led to the popularity of zoos, we enjoy and are entertained by our ability to control other animals. In the case of this video, elephant painting itself, playing music, and kicking a soccer ball, we delight in the fact that we have been able to pass on our knowledge on another animal and are able to control it for our entertainment. This is a very common practice among zoos, where they claim to be educating the public about the animal when in reality they are teaching animals human behavior which is not natural to the animal. Some may argue that this deepens our relationship with the animal. I have to agree with Malamud however, while I did enjoy watching an elephant paint a self portrait, I also understand that this wasn’t the elephant expressing itself through a creative medium it was a learned behavior that is not natural to the animal and was only preformed after training Suda through a means of punishment and reward. Another way of expressing our control over animals.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eerUnxonS-I

A Man Among Wolves is a documentary made by National Geographic. This video is just a 3 minutes clip from the original 2-hour documentary. It mainly tells the life of Shaun Ellis who chose to live his life among a pack of wolves. The video starts with the narrator saying, “This is Shaun Ellis, he’s done something few would dare and few would understand.” Then Shaun sat in front of the camera and said, “For me, personally, it costs family, home, security, financial commitment, everything is gone.” A great portions of this video is depicting the kind of life Shaun had with wolves: he washes his hair by the river, he roars to the wolves, he howls with the whole pack of wolves, he eats raw meat with wolves and he licks wolves very intimately. The narrator then talks about Shaun’s scientific purposes, which are studying and writing about wolves in Poland and America. He dedicated all his time spending with a pack of wolves and eventually became the “alpha male” in the pack. At the end of the video, the wild life park Shaun and his pack of wolves live in was briefly introduced. There are fences separating the tourists and the animals. One scene that is very worth noting is that as tourists are on the one side of fences observing animals, Shaun is on the other side cuddling with a wolf.

Throughout the whole video, there is a very typical narrative voice of a male as you could hear in any documentary. The background sounds are wolves howling, trees whirling and bird singing. All of these sounds give us a sense of nature, telling us that Shaun and his pack of wolves are living in a truly natural environment.

This amazing video is also relevant to Malamud’s arguments in Zoo Spectatorship. In Malamud’s essay, he is completely against the zoos; he says that spectators disrespect animals in the zoos, and zoos just don’t allow animals to be themselves. In this video, what Shaun does was not just observing wolves at distant. He chose to become one of them in the most natural conditions. He didn’t disturb the original life of wolves at all. Malamud states that, “zoos celebrate people’s power over animals, our penetrating ability to keep them and watch them.” (228). However, Shaun regards himself as one member of the wolf pack. And by doing this, he could appreciate the real beauty of these amazing creatures. So I think Malamud would support Shaun’s way of interacting with the wolves even though it seems extreme to most people.

The purpose of this video is purely educational. As Shaun said himself, “ I wouldn’t be doing this if I don’t think it wouldn’t make a difference.” He successfully showed that man could live in harmony with wolves as long as man respect their way of living.

Sources:

Malamud, Randy. Zoo Spectatorship. New York: New York University Press, 1998. Print.

Recent Comments