Today I attended a talk that was related to the bird exhibition currently being held at Williams Art Center that commemorates the hundredth anniversary of the death of Martha, the last passenger pigeon. This talk was given by two Lafayette Biology professors, Dr. Butler and Dr. Rothenberger. In this post, I would like to tell those of you who missed the talk about what I learned from it and how it connects to what we are learning in class.

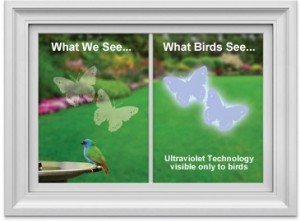

I would like to pose a question to you: How many times have you walked into a sliding door? The answer is probably several times, even though you are a human being with a knowledge of doors and windows. One can only imagine how many times birds, who lack this knowledge, crash into sliding doors and windows. Since birds are flying so quickly, many of their crashes are fatal. Windows are the primary cause of bird mortality. Between 100 million and 1 billion birds die from collisions with windows each year. However, the Lafayette Department of Biology is currently working with the Department of Civil Engineering and EREN (Educational Research and Educational Network) on developing ways to lower the number of bird mortalities at Lafayette. You can help them with this by emailing Dr. Mike Butler with a picture/location each time you find a dead bird on campus.

The interesting thing to take away from this is that windows, although a human invention, are not a consequence of the Industrial Revolution. This talk was different from the lecture previously given by Michael Pestel because it contrasted Berger’s idea that our disconnection from animals and consequent reduction of them is a product of the Industrial Revolution. According to Dr. Rothenberger, overexploitation of animals by humans occurred well before the Industrial Revolution. For example, the Steller’s Sea Cow was hunted to extinction in 1768, a mere twenty-seven years after the discovery of the species. Another example are the Moa birds which were hunted to extinction in 1400.

Although clearly humans have diminished the welfare of animals and caused mass extinctions, none of the books that we have read in class seem to consider the possibility of reversing our past mistakes. Dr. Rothenberger discussed the possibility of resurrection of extinct species via three methods: backbreeding, cloning, and synthesis. Backbreeding is a form of artificial selction to achieve an animal breed that resembles an extinct species, cloning is creating a viable embryo from a body cell and an egg cell, and synthesis involves using fragments of the DNA of certain extrinct species to synthesize the genes for certain traits and then splice those genes with the genes of a related species. However, the ethics of these processes are highly controversial and some experts question whether it will be practical. For me, the idea of resurrection just raises further unanswerable questions such as: How will we reintroduce these species to the environment? How will they interact with present species? Who will take care of them to prevent their re-extinction? Since these questions do not seem to have practical answers, my conclusion from this talk is that it will be very inefficient to try to resurrect an extinct species and resurrection may end up causing more problems than it solves.

For those of you interested in learning more about this topic, there will be another talk called the “Ethics of De-extinction” at 7 PM on 10/27 in Oechle 224! I am going and I hope to see you there.

References:

Berger, John. “Why Look at Animals?” About Looking. New York: Pantheon, 1980. 3-28. Print.

“Bird Window Collisions – Tips on How To Prevent Wild Birds From Crashing Into Your Windows.” Birdwatching-Bliss.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 16 Oct. 2014.

Butler, Mike and Megan Rothenberger. “The Loss and Resurrection of Species.” Lafayette College. Williams Arts Center, Easton, PA. 16 Oct. 2014. Lecture.

Leave a Reply