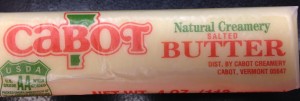

In this product made by Cabot Creamery, found right in Lower Farinon, the message of what the conditions the animals used in this product endure is misleading. This stick of butter depicts 4 cows, in seemingly good health, mindlessly able to graze throughout the thousands of acres of fresh green grass on the traditional farm setting that is available to them. The front of the package is labeled “Natural Creamery” in distinguishable lettering, being able to be clearly seen through its green font, trying to show people that their product is “natural”. Although many people still view this type of farm setting as the normal setting for most farmers, this is sadly not the case. This is a smart way of advertising the butter product this company is trying to sell due to the trickery this image uses. Many people actually want the animals that they eat or the animals that are used in the process of producing their food to live a happy and healthy life, and for many, this simple picture will satisfy their desires. These types of advertisements are purely a way of setting a peace to the mind of the users, and many will not think about where their food really comes from, just if the product says that these animals used were happy and healthy.

In this product made by Cabot Creamery, found right in Lower Farinon, the message of what the conditions the animals used in this product endure is misleading. This stick of butter depicts 4 cows, in seemingly good health, mindlessly able to graze throughout the thousands of acres of fresh green grass on the traditional farm setting that is available to them. The front of the package is labeled “Natural Creamery” in distinguishable lettering, being able to be clearly seen through its green font, trying to show people that their product is “natural”. Although many people still view this type of farm setting as the normal setting for most farmers, this is sadly not the case. This is a smart way of advertising the butter product this company is trying to sell due to the trickery this image uses. Many people actually want the animals that they eat or the animals that are used in the process of producing their food to live a happy and healthy life, and for many, this simple picture will satisfy their desires. These types of advertisements are purely a way of setting a peace to the mind of the users, and many will not think about where their food really comes from, just if the product says that these animals used were happy and healthy.

This image exploits what John Berger would describe as “animals of the mind”. Berger, would argue that we view animals in our mind, and then it is these expectations that our mind creates that dictate how we view animals, not due to how animals truly are in their nature; “They are objects of our ever-extending knowledge” (Berger, 16). The typical image that people would associate with cows/making butter is a farmer manually milking a cow out on his ranch, and churning the butter manually. Therefore, the advertisement that this company utilizes wants to mimic the imagery most people associate with butter, not only so that they will associate this product to butter, but also because they want their food to be made from happy natural animals. People imagine what animals are generally like in their head, creating these grand images and depictions of “animals of the mind”, but once the people actually see the reality of these animals, they will be utterly disappointed. Most of these cows live an unhappy and sick life, living to only fractions of their wild life expectancy, and most are never exposed to the green grass that is depicted in this picture.

Jonathan Safran Foer would want us to look directly at the natural setting that is depicted in this image, and know right away that the “natural” that is company proclaims isn’t really even a plausible thing. Factory animals, as he says, “In a narrow sense it is a system of industrialized and intensive agriculture in which animals — often housed by the tens or even hundreds of thousands — are genetically engineered, restricted in mobility, and fed unnatural diets (which almost always include various drugs, like antimicrobials). Globally, roughly 450 billion land animals are now factory farmed every year. (There is no tally of fish.) Ninety-nine percent of all land animals eaten or used to produce milk and eggs in the United States are factory farmed. So although there are important exceptions, to speak about eating animals today is to speak about factory farming” (Foer, 34). Natural, as he says, isn’t even a defined term, how can you define something as natural, when 99% of the farming done in the United States is done in a factory setting? He would reminisce on how only 2 generations, virtually all farms were family farms, and would think about how all of those farms have been replaced with factory farms that have no legal laws on the treatment of animals. Foer would want us to see this tactic that the advertising is trying to exploit and understand that the cows’ lives are not like how they are portrayed, so we can become more conscience consumers.

Works Cited:

Berger, John. “Why Look at Animals?” About Looking. New York: Pantheon, 1980. 3-28. Print.

Foer, Jonathan Safran. Eating Animals. New York: Little, Brown, 2009. Print.

Leave a Reply