It’s been some time since the Easton Library Database team has been active on this space, but we’re returning for another summer’s dive into the archive with a new series of blog posts.

This series, which we’re calling “Shadows of the Library,” is in the spirit of Matthew Pearl’s The Poe Shadow (a collective favorite among the team) in which we share some history-inspired fiction based on the discoveries we make. Many discoveries in archival research, as those who have done this kind of work know, lead to dead ends, missing connections, and puzzles that can’t be solved. Matthew Pearl is a master at taking these research dead ends and imagining plausible ways to fill in the gaps—and offer some wisdom about how little we know about history. (Simon Schama’s Dead Certainties is another fine example of this approach to historical research and writing.)

We’ll continue to write about discoveries, questions for readers, and other matters, but these “Shadows” pieces will offer an imaginative channel for some of the intriguing—and often frustrating—finds we’re making among these materials.

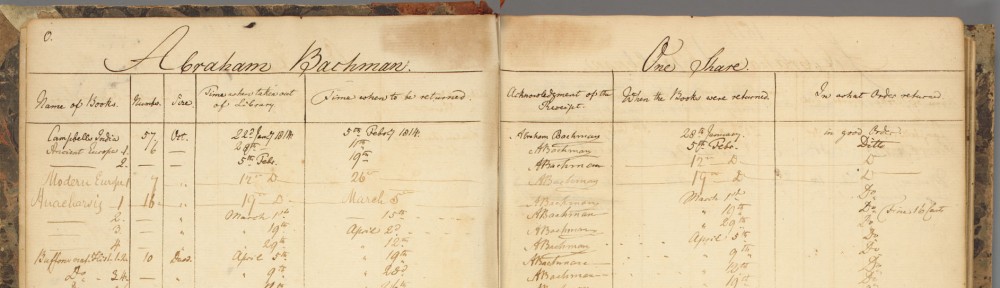

And just a quick update on the project: We’re deep into the third of five ledgers, which puts us in the neighborhood of 1830 or twenty years into the borrowing records for the ELC. We’re still transcribing the ledgers, and this summer we plan to start adding biographical data on the patrons and making progress on finally getting this database live and available to the public. Thanks for your patience, all who have been following this project in various venues, and stay tuned for more to come.