Abstract

This section analyzes what it meant to teach with an anti-racist pedagogy and how to adapt it to a technical classroom best. Professors must adopt an anti-racist pedagogy into STEM education to ensure that future engineers know how to form and argue opinions and be critical and social thinkers (Gurin, Dey, Hurtado, Gurin 2002). When adopting this pedagogy, we understand that each professor comes at this with a different comfortability level and perspective. Once an editor at Rethinking Schools Magazine, Bill Bigelow believes it is important to start each professor with the right toolbox to adopt an anti-racist pedagogy. To start, all educators need to note that neutral and inoffensive language disregards the conflicts and diversity endured to achieve the end product (Bigelow, 1978). For example, for a professor to teach about modern gynecological tools without discussing the enslaved women on whom these tools were non-consensually tested would be a gross injustice. Students and professors must welcome the discomfort of many of these conversations because racism is ingrained in our society. Ignoring it is ignorant and a disservice to the students trying to obtain a fully diversified education. Applying an ethical pedagogy to a technical curriculum can be challenging, but it can be done effectively with the right tools.

The Pedagogy

Why Is This Important?

College professors are responsible for shaping the minds of the future. Michael Harris, Professor of Higher Education at Southern Methodist University and author of Understanding Institutional Diversity in American Higher Education acknowledges, “Observers of higher education generally acknowledge the necessity of institutional diversity to support a system of colleges and universities that proves flexible, responsive, and adaptable for a range of purposes” (Harris 1). Diversity and inclusion are no longer expected to just be seen statistically, but also to be taught and intertwined throughout campus. In this, it is the educator’s job to “give perspective to more fully understand society” (Bigelow, 1978). This teaching style has been discussed and slowly adopted over the past 50 years, but more educators must integrate this pedagogy into their curriculum. Bigelow continues, “It highlights the injustice of all kinds— racial, gender, class, linguistic, ethnic, national, environment— to make explanations and propose solutions. It recognizes our responsibility to fellow human beings and the earth […] Aims to make the world a better place” (Bigelow, 1978). After all, is engineering not meant to better the world? Is it not meant to make society a better place? To make our lives better? Students must internalize this pedagogy to ensure a future more inclusive of all.

When students attend a Liberal Arts College, they expect to obtain a robust and holistic education, meaning they will be offered multiple perspectives and opportunities when learning about a historical event; however, there is a disconnect when applying this pedagogy to a STEM classroom. For example, when students learn about Christopher Columbus, they are not only taught about all the land he explored and how much money he made for Spain, but we also focus on the injustices that occurred and the oppression that came out of his explorations. Today, it would be unfathomable to discuss Columbus’s accomplishments without also discussing the heinous crimes he committed; yet, we discuss engineering innovations without mentioning the overlooked, marginalized, and exploited people it took to achieve the invention. For example, a multitude of engineering disciplines could discuss the invention of the traffic light. Whether it be mechanical, electrical, or computer engineering, the techniques used to create the traffic light could be applied to all; however, little is taught about its inventor Garrett Morgan, a Black inventor from Cleveland, Ohio who paved the path for many Black engineers to come (Biography, 2018).

Applying it in the Classroom

Professors start the anti-racist pedagogy journey at many different stages. It would be inherently wrong to practice an anti-racist pedagogy without being patient with its followers. Enid Lee, the director of a Canada-based consulting firm dedicated to implementing an anti-racist pedagogy into the curriculum, outlines some very simple yet effective steps professors can take toward adopting an anti-racist way of teaching.

Detailed steps are outlined below, but Lee notes that it is up to the individual to decide where they start their journey. Lee suggests starting with the basics. Just as one would do when learning anything else, consider what this means to you personally and in the context of your career (Lee, 2009). It is important for the professor to reflect on their practices and beliefs individually and how they may or may not follow an anti-racist way of teaching. Educating oneself on this method and reading what experts have published before them is crucial. Professors will need to take a step back and think hard about what perspective they are teaching from and whom they are marginalizing or forgetting because of that. Lee encourages faculty to discuss socio-technical issues with their peers and students to grasp what it truly means to hear and appreciate multiple perspectives (Lee, 2009). Identifying the boundaries established by the engineering department and Lafayette College is essential to understanding where the department currently stands before progressing forward with pedagogy changes.

Next, Lee suggests that teachers incorporate anti-racist pedagogy into one unit on their syllabus. In doing so, professors are given the time and space needed to practice this way of teaching in small doses (Lee, 2009). They will also be able to receive feedback from students regarding the unit and will be able to make changes in the future. This pedagogy will not be mastered overnight; professors should not expect it to. A way to do this in a technical classroom would be creating a unit in which the students do a project on an invention and uncover all the unknown information about its inventors. In this, students will learn about the technical invention (how and why it was created, its triumphs and failures, etc.) and the people behind it.

Once the instructor feels comfortable teaching such a unit, they can start incorporating these methods into every lesson they teach (Lee, 2009). Professors can give context and background on all systems they teach. The professor must first be comfortable teaching with this methodology because it can be uncomfortable for students to learn this way. Self-reflection is a crucial part of this process on all ends. Students will be pushed to rethink the world around them, which can be challenging coming from a background where this is not the norm. Another challenge professors may face while integrating anti-racist pedagogy into their teaching is the expectation many engineering students hold that STEM classes will be technical, with answers that can simply be judged as right or wrong (Rossmann, 2022). While integrating such topics into their courses, professors must be able to effectively teach students that the “optimal” solution to engineering problems is not always the most ethical or just approach and the context surrounding the problem, including how the “problem” itself is defined just as vital, if not more so than the technical aspects of engineering education.

Students retain information better when they know they will be tested on it, so like any other systems exam, ethics questions can also be included. For example, solve the system, explain who the inventors were, and how they created it. Students could be tested on their understanding of the political and social contexts surrounding engineering topics they are learning about in class.

Teaching Example: The Traffic Light

Overview

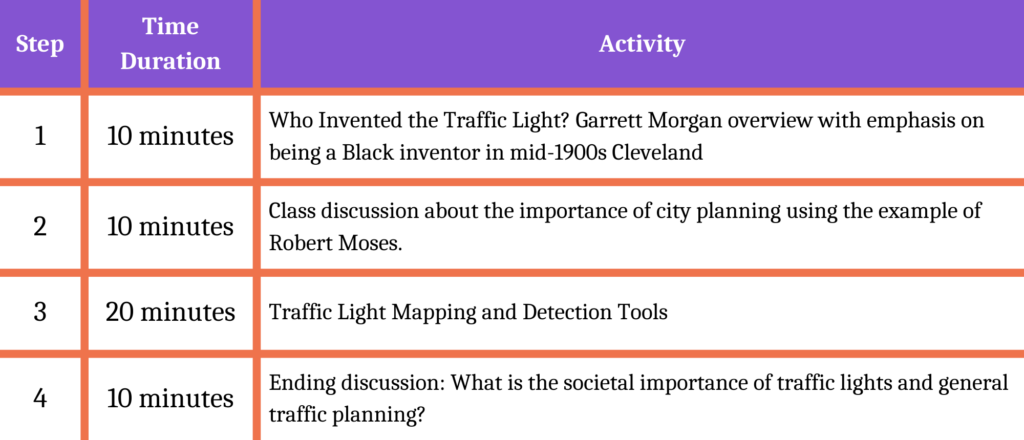

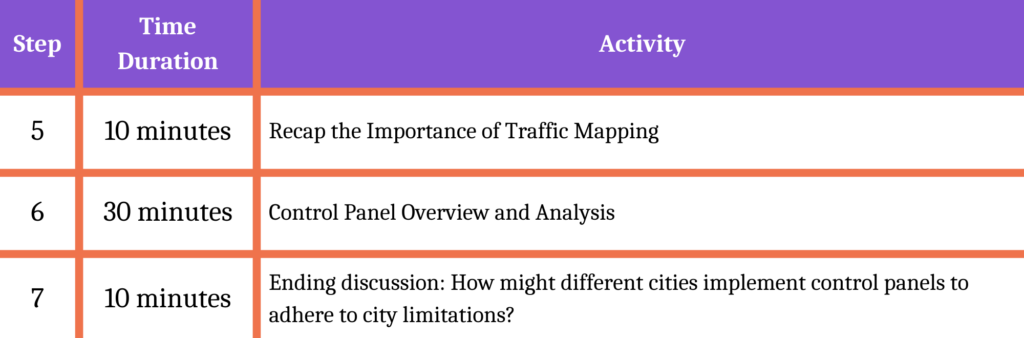

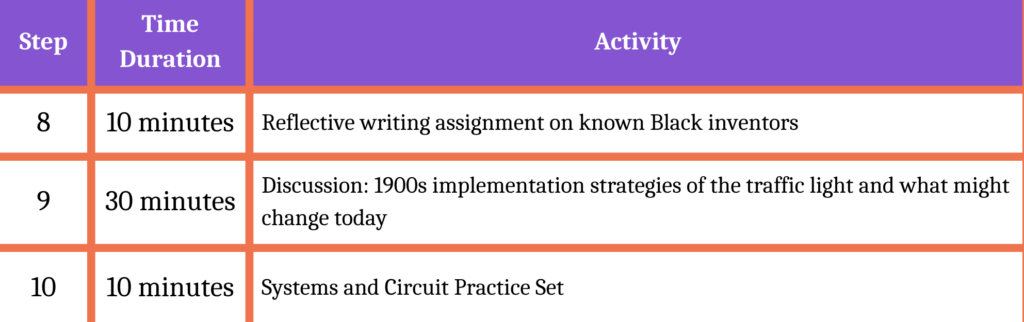

Below, is a simplified outline of a lesson plan for three fifty-minute Electrical Engineering classes (1 week). In this example, the professor will teach the necessary technical equations and give relevant historical background to amplify the students’ social awareness. The lesson plan outline is depicted below, with a detailed description of each step following.

Mock Lesson Plan

Figure 2, Day 1, Lesson Plan Day 1, As created by Authors

Figure 3, Day 2, Lesson Plan Day 2, As created by Authors

Figure 4, Day 3, Lesson Plan Day 3, As created by Authors

The Lesson Plan Explained

- To start the lesson, we expect professors to give adequate background context on the invention’s social, political, and overall general context. Providing students with the background of the problem and proposed solution allows them to think critically about the greater issue trying to be solved (Gurin, Dey, Hurtado, Gurin 2002). In this example, the background context also sheds light on a Black inventor that may have been overlooked otherwise due to his stature in the early 1900s.

- Further context on what is happening in the city planning field around the nation and the issues and injustices arising. It is important to learn about Robert Moses, a notoriously racist city architect for New York City in the 1900s (Britannica) while learning about the invention of the traffic light because the traffic light enabled Moses to enforce his racist agenda. This information allows the student to think about other inventions that lead to the further marginalization of groups and how to avoid this issue in the future.

- While the background and social context of the traffic light are largely important, the student must also learn the technical aspects of inventing and constructing an automated light system. This will be split across the entire week as it is a long and intense circuit and system process (Utrecht University Institute of Information and Computing Sciences).

- Connect the full lesson circle by ending with another class discussion. In this discussion, students should be asked to think beyond the scope of the day’s lesson and apply the information to a greater social context. This is important for students to practice in the classroom so that when they enter the labor force, they can apply the lessons learned in the light traffic example to modern problems and propose dynamic solutions.

- Reinforce what was learned at the beginning of the week to ensure the students and the professor start on the same foot. Recap the technical skills learned in the last class and the social issues discussed and their importance. It is important to continuously reinforce the ideas the professor wishes the students to remember. The brain must be trained to re-learn and re-think in this anti-racist manner, just like any other muscle would have to relearn a sports skill after an injury.

- Like on the first day, staying on top of the technical and mathematical skills needed to create an efficient traffic light system is important. Professors should note what “efficiency” means in this case and how the definition might change from community to community.

- Follow up the before point with an ending class discussion of how students would change the traffic system in their town. Ask them to think about the current issues, why the infrastructure is currently set up that way, possible solutions, and the implications of those solutions.

- Ask students to think of other Black inventors that may have been overlooked in history. Why did this happen? Is this trend changing? As students about to work in the industry, how do you avoid this happening in the future? Asking students how they might make a change is an effective way of bridging the social context presented earlier in the week and encouraging them to think about all the pieces more dynamically.

- Open the discussion further to the social and political context in 1900s Cleveland and how that affected the nationwide traffic light implementation. Push students to think about if they were to invent and implement the traffic light today, other than technical advancements, what policies and practices are in place that change the creation, distribution, and implementation of the traffic light.

- Finish the week with a circuit and systems problem set that focuses on the technical aspects of creating and installing a traffic light system.

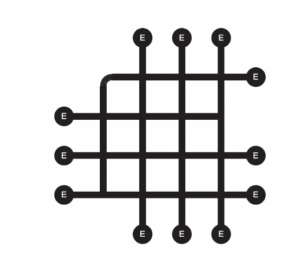

Sample Exam Question

The below circuit represents a traffic light system that is being considered for the town center of Easton. Explain, mathematically, why or why not this would be a good alternative. Also, explain in words some possible implications of this proposed infrastructure, how we might have seen something similar in the past, and the changes you suggest to improve the traffic system.

Figure 5, Traffic Grid, Sample Traffic Grid for an Exam Question, Utrecht University Institute of Information and Computing Sciences

General Lesson Plan Trends

Like many technical-based classes, the outline above focuses on reinforcing the concepts learned at the beginning of the week throughout the week. This approach was also taken with the social concepts as the plan sets aside time each class period to think about the social and ethical implications of the technology. Asking students to consider historical and possible future solutions allows them to think critically and analyze all aspects of the problem at hand. Breaking up the ethical conversation into smaller, more pointed discussions helps the professor and students understand the social context and how to better the process going forward.

To learn about the Economic context of this project click here.