Introduction

In this section, we explore the social construction of race and racist structures in sociotechnical and educational spaces. More specifically, this section outlines how race—in its contemporary definition—affects engineering, education, and the future of technology by ingraining itself within the foundation of these social systems. The scope of our project focuses on the Bachelor of Science and BSE engineering programs at Lafayette college, however, it is necessary to take a step back from this focus to understand race and its expansive effects on STEM education–both nationally and at Lafayette. For this reason, we begin with an exploration of the definition of race and how it has been colloquially accepted in post-eugenics society. We then move to conceptualize race itself as a technical system. In other words, this section of our analysis explains how race has been used as technology and where it fits into our proposed educational solutions. Finally, we take a brief examination of current anti-racist pedagogical efforts being done at Lafayette. From here, we move on to the various success and limitations of these in the context of anti-racist education. We affirm that equipping professors with tangible training in implicit bias will allow courses and discussions across the disciplines to create a safer space for students of all backgrounds.

What is “Race”?

As defined by Smedley & Smedley in their article Race as Biology is Fiction, Race as a Social Problem is Real, race is a socially-constructed ideology that inherently “seeks to explain human population differences in health, intelligence, education, and wealth as the consequence of immutable, biologically based differences between ‘racial’ groups.” They elaborate that racial distinctions are not genetically discrete, measurable, or scientifically relevant (Smedley & Smedley, 2005). Despite strenuous efforts from eugenic-supporting scientists, there is no biological categorization or measurement that can be placed on racial differences. In contemporary culture, race has come to classify human groups by skin color separating this identity from human ethnicity and culture creating shared experiences for racial groups. The definition of these racial lines has been blurred and redefined countless times as policy has changed and evolved. However, through all definitions, race fulfills its function to divide classifications of people and inherently create systems of hierarchy in social settings. This leads to public policy coming to fruition around the racial formation to serve the needs of the privileged “racial groups”. Racial formations themselves are used as political power to brand certain racial groups as beneath others (Omi & Winant, 3). Here is where we begin to see racial definitions bleeding into technical systems and engineering education. Due to the fact that certain racial groups have not been privileged to have a seat at the table, our social and technological advances have been created to serve white individuals. By analyzing our own racial identities and how we interact with technology, we are able to see how the two cannot be separated and should be redefined in tandem. It will additionally highlight how race has permeated nearly every aspect of our society.

As Langdon Winner writes in Do Artifacts Have Politics? Political technology is the notion that technology can be not only analyzed for its societal benefits and impact “but also for the ways in which it can embody specific forms of power and authority” (Winner, 1980). Drawing upon the definition of race, racial structures lend themselves to hierarchy and prejudice. Race exists in order to cause separation and division between humans. Political technology acknowledges that science will follow the same hierarchical systems as race. Since white individuals hold the power and agency to completely influence innovation, the systems they create will uphold the status quo. For example, Robert Moses was the city planner for New York and held great influence

on city infrastructure for nearly half a decade. Most importantly, he commissioned the construction of Long Island parkways’ indicatively short overpasses. Moses intended these overpasses to prohibit mass transit travel to the Island and keep what he claimed were “lower class” families segregated from the beaches (Winner, 1980). This is an example of explicit bias within technology caused by the inventor. In essence, political technology can be used synonymously with technology. Because of the implications in our society and human influence, no technology can be fully removed from its prejudices and bias.

Technological determinism is another aspect of technological society-making that is being debunked by scholars in the field. This is the notion that technology and technical systems determine the course of human development void of human interference or direction. In their book “The social construction of technological systems: New directions in the sociology and history of technology”, Bijker, Hughes, and Pinch define technological determinism as “the claim that technology causes or determines the structure of the rest of society and culture. Autonomous technology is the claim that technology is not in human control, that it develops with a logic of its own. The two theses are related” (Bijker et al., 2012). This 21st-century Manifest Destiny is yet another obstacle to breaking down racial prejudice in socio-technical and educational spaces. Innovators may believe that engineering progress translates directly to social progress when this could not be further from the truth. In discussing the ways determinism can present itself, Jonas Hallström writes

Technological determinism can take the form of an idea, theory, or a way of explaining technology development in history or the present, but it can also take the form of actual material structures that—implicitly or explicitly—permeate and influence society, or, at least, this is what some researchers and scholars claim (Hallström, 2022).

If technology is not questioned, the already present prejudices will snowball and expand exponentially without any structural reassessment. Integration of racial prejudices and discrimination with technology is our first largest obstacle to combating racist pedagogy.

Racist Histories & Methodologies in Technical Spaces

Access to STEM & Engineering Education

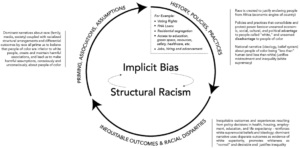

With an understanding of racialized sociotechnical systems, we can now cover key definitions for conceptualizing race as its own technology and furthermore what role it plays in an undergraduate-level engineering classroom. Firstly, it is important to understand that racist education and engineering of the past can be both passive and active. The biases ingrained in these systems can be explicit, usually the action of individuals with discriminatory motives, or implicit coming from within the system as symptoms of overlooked prejudice. Implicit bias is a subconscious and structural form of racism that allows bias systems to continue. Examples of implicit bias are present in technologies such as facial recognition or automatic soap dispensers which were only given white skin tones as data and could not perform properly for dark-skinned individuals. The engineers may not be inherently making conscious racist choices, however, the lack of representation and inclusion has allowed the systems to exclude minority groups (Mone, 2016). Explicit bias in engineering is present when engineers and innovators are making knowledgeable choices that disadvantage certain groups. This is less common, and for the purpose of our capstone, we will primarily focus on implicit biases in engineering education.

From childhood, there are significant differences in access to STEM education between white and POC students. In a recent study published in the Journal of Engineering Education, authors London, Lee & Ash found notable disparities in sustained academic interest in STEM fields based on access to early childhood education. From their findings, they were able to link Black imposter syndrome and lack of engineering resources to inadequate exposure to STEM learning in elementary schools. Additionally, the journal highlights that Black students’ largest reasons for avoiding technical field aspirations are due to “not feeling smart enough” or feeling inadequately “prepared[…]to succeed in STEM” (London et al., 2021). This systemic, rather than systematic, disadvantage for Black and Brown students is one of the many examples in which current racial biases in engineering education struggle to represent the diverse whole. Colloquial segregation of schooling is how race asserts itself in the technical and educational realm. This discrimination against Black students is set as a precedent and follows students into higher-level education. A 2019 report by the National Science Board found that 60% of all engineering degree recipients identified as white. Black students comprised the second least represented group at less than 10% (NSB, 2019). This not only limits the ability of the workforce to fully incorporate diverse perspectives, but it upholds a biased and segregated system that must be entirely restructured to address bias.

Lafayette Demographics

We can use this information to now view Lafayette’s Engineering Division as a case study and analyze the current state of diversity efforts. Following the murder of George Floyd in 2020, colleges and universities across the nation ramped up efforts to tackle racist biases in educational settings. Lafayette was no exception to this call to action. Across the division, professors and students alike worked to increase the awareness of potential biases and injustices within Acopian.

Our first analysis was of the current demographics of the Lafayette engineering division. According to Lafayette Engineering’s Diversity and Inclusion website, nearly 25% of engineering students are from “underrepresented groups”(Diversity and Inclusion · Engineering · Lafayette College, n.d.). It is unclear exactly what this term represents, however this certainly falls below the 40% average of non-white engineering degree recipients. The division also highlights its partnership with the Posse Foundation to increase accessibility and representation of underrepresented groups in engineering. There are a variety of multicultural, extracurricular groups focused on creating cohorts within the engineering majors. Some of these include the Association of Black Collegians, Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers, Society of Women Engineers, and Minority Scientists and Engineers. Due to their extracurricular status, these clubs are limited to working from an outside perspective.

Lafayette Status Quo

Professor Perspectives

Beginning this project, we had a discussion with Professor Jenn Rossmann of the Mechanical Engineering department about her own work and experiences with integrating anti-racist technological teaching into the classroom. Last spring, she taught a course entitled “Race & Technology” which tackles these exact issues. While this course offers invaluable insight into the potential disadvantages of current technical practices, it is still its own separate entity presenting issues of accessibility to registration for most students and especially B.S. engineers. Our project again is hoping to work towards the integration and existence of anti-racist practices across all engineering classes and curricula. Prof. Rossmann was able to share with us the current practices of the engineering departments for expectations of anti-racist teaching. Currently, all new professors undergo a year-long training program tackling several different areas of social justice and equitable education training. Additionally, there are voluntary workshops and discussions throughout the academic year tackling how to handle these conversations in an engineering context.

When we focused our project on professor training and workshops, Prof. Rossmann presented some of the potential obstacles that we may face moving into a professor-centric solution model. Firstly, mandatory training may not be received well by an entire faculty. Mandating these forms of workshops is one of the ways to ensure the material is being received by all faculty; new and tenured. Additionally, in an engineering course, professors will already be set on a schedule to tackle a large amount of material in 15 weeks. Adding discussion topics and external material to this already large workload will prove daunting to some professors and unappealing to others. This insight was incredibly valuable in shaping how we plan to implement and strategize our solution workshops moving forward.

To read about the Political Context of this project click here.