The Great Hack

Figure 9. Zuckerburg Senate testimony (Vox, 2018)

The Great Hack is a Netflix documentary that explores the consulting company, Cambridge Analytica. Cambridge Analytica is a British consulting company that relied on the mining of Big Data to make business decisions on political campaigns. Not only does the mining of Big Data lead to biases and skewed results, but most of Cambridge Analytica’s data was acquired as a result of a privacy breach of millions of Facebook profiles. This privacy breach enabled Cambridge Analytica to acquire over thousands of data points on every American voter. Ultimately, giving them enough power and information to tamper with national elections in the form of political propaganda.

Cambridge Analytica has a long history of election tampering ranging from the Brexit Vote to presidential elections in Trinidad and Tobago. However, Cambridge Analytica is best known for their work on the 2016 Donald Trump campaign. The consulting company used their data and information on American voters to send them personalized ads related to the election. This results in millions of people getting personally targeted without their knowledge or consent. The company doesn’t waste time and money targeting individuals with their minds made up, but instead identifies persuadable voters in swing districts. Using psychological profiles, Cambridge Analytica appeals to issues that individual voters will be influenced by.

The psychological profiles are constructed through Facebook user data. Seemingly innocent Facebook quizzes such as “What breakfast food am I” or “What superpower would I have” and the data on your actual profile such as your friends and your job are compiled into thorough psychological profiles. Additionally, the documentary states, “Apps on Facebook that were given special permission to harvest data not from just the person who used the app or joined the app, but it would also then go into their entire friend network and pull out all of their friends’ data as well. If you were friends with somebody who used the app, you would have no idea that [they] just pulled all of your data.” Thus, even if you didn’t participate in the quizzes or grant companies access to your data, your friends may have done so.

After gaining access to only a few thousand people, Cambridge Analytica built a data profile for every voter in the United States and targeted those who could be swung in important districts. Targeted individuals were flooded with information regarding “crooked Hillary” and benghazi. This information wouldn’t be associated with Cambridge Analytica or with the republican party so users were unaware that these were really pro-Trump ads. Formerly apathetic voters became empowered to share more misinformation and go out to vote without knowing they’d been targeted and subjected to pro-Trump ads specifically aimed at their psychological profile. One former Cambridge Analytica employee called the company a “Weapons-Grade Propaganda Machine.”

Ultimately, allegations surrounding the 2016 US Presidential Election made their way to the Senate resulting in Mark Zuckerberg’s senate hearing regarding data privacy. Zuckerberg claims that Facebook stopped information sharing and asked Camrbidge Analyica to delete all user data months before the hearing, however Brittany Kaiser, former Cambridge Analytica employee and documentary participant, claims this is not true. Companies like Facebook play a large role when pushing the ethical boundaries of what’s acceptable in the online world. Most, if not all, of their revenue comes from selling user data or posting advertisements. This becomes a breeding ground for exploiting their users, as companies like Cambridge Analytica can buy data and advertising space on their platform.

The discussion of the “Do So” campaign in Trinidad and Tobago further highlights the power of data mining on elections. Cambridge Analytica flooded social media with fun posts and catchy songs about Do So, a “young people’s” movement against voting and designed to increase voter apathy. These ads were unaffiliated with Cambridge Analytica or either political party so the movement seems organic. There are two major political parties in Trinidad and Tobago: the People’s National Movement, mostly supported by Black voters, and the United National Congress, mostly supported by Indian voters. As Cambridge Analytica predicted, young PNM supporters did not come out to vote but young UNC voters came out, “because their parents made them.” resulting in a landslide victory for the UNC. This kind of elicit election tampering, especially by British company Cambridge Analytica towards a former colony, is extremely worrisome and poses huge ethical questions.

The business model of Cambridge Analytica provides a lot of ethical implications for the use of Big Data, where it was acquired and how it’s being used. When business models solely rely on the selling of personal data, it’s unlikely they will make ethical decisions about how this data is being used. Former employee Kaiser states, “In the end, [the voters] are the ones that go to the ballot box and make their decision.” This raises the question of how appropriate the uses of data mining are within different fields. Kaiser was not a Data Analyst but faced a predicament that many future data analysts might find themselves in.

TikTok Privacy Concerns

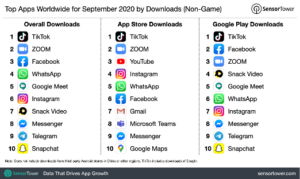

Figure 10. Top Apps Worldwide for September 2020 by downloads, coming one month after President Trump announced an impending ban on TikTok. (SensorTower, 2020)

Similar to Facebook, we’ve seen a growing number of concerns about user privacy when it comes to the new social media app, TikTok. TikTok is a video sharing app for iOS and Android devices that has risen to large popularity over the past year. TikTok’s history, however, dates back as far as 2016, when it was initially launched as “Douyi” in China. The following year, in 2017, the app was relaunched as TikTok by its Beijing based parent company, ByteDance. While TikTok and Douyin are similar apps using the same software, the distinction of the two lies in their projected network and global reach. Douyin remains to be a Chinese only app bound by the censorship laws of their country, resulting in the removal of content that may displease the Chinese government. TikTok, however, has gone on to become the most downloaded app in Apple’s iOS App Store with over 33 million downloads in Q1 2019 (SensorTower, 2019). With over 800 million active users worldwide (Datareportal, 2020), it is no surprise that TikTok has been gaining more media attention along with concerns from users and foreign governments.

When it comes to the information that TikTok collects, it doesn’t harvest more data than the typical social media app such as Facebook or Instagram. The issue with the popular app, TikTok is not how much data it is harvesting, or even how it’s being harvested, but the uncertainty in how that data is being used. The Chinese ownership of TikTok is what creates the uncertainty with much looser data privacy laws than those required by American owned apps in the United States. Though neither country provides an extensive amount of privacy for users, the risk posed by Chinese apps come from the countries National Intelligence Law, putting Chinese data companies at the whim of their government’s needs. The Chinese National Intelligence Law has the ability to force Chinese owned apps to cooperate with the government. Though TikTok has repeatedly denied that it has or would ever share user data with the Chinese government, the National Intelligence Law makes it so they would not be able to tell us even if they did.

It is important to look at the political context at play when discussing the banning of the popular app, TikTok. While many countries that have started to raise concerns about TikTok, India was among the first. India’s banning of TikTok, and 60 other Chinese apps, came in the wake of a violent border dispute between India and China leaving 20 Indian soldiers dead. With an unknown amount of Chinese casualties, the June 17th dispute remains the most violent incident between these two countries in 50 years (Abi-Habib, 2020). In an opinion voiced by Liuqing Yu, an Analyst at The Economist Intelligence Unit, the banning of Chinese apps in India could be interpreted as a form of economic retaliation, meant to send a signal to China (CNA Insider, 2020). Still, the national security concerns posed by Chinese apps are very valid given the uncertainty of how they use the data collected from said apps.

India’s banning of TikTok proved to be very influential, raising concerns of national security around the world. One of the most notable world powers that came out in support of banning TikTok was The United States. This is coming after the 2016 United States democratic election who’s outside influences posed threats to democracy at the highest level. In the documentary The Great Hack, we learned about how data company Cambridge Analytica used “5,000 data points” on millions of Americans as a means to psychologically profile and target them with specifically tailored content. Furthermore, we’ve seen the United States take action against election interference in this way in a report by the Senate Intelligence Committee in July of 2019 that included recommendations for securing the 2020 election. In the report, they acknowledge “Russian disinformation efforts may be focused on gathering information and data points in support of an active measures campaign targeted at the 2020 U.S. presidential election”(Report of the Select Committee on Intelligence United States Senate on Russian Active Measures Campaigns and Interference in the 2016 U.S. Election Volume 2). It is clear that the mishandling of user information has been a point of concern in the United States for many years. Combating this threat means taking an active role in user privacy and controlling the data that foreign influences have access to. There are infinite possibilities as to how the mining of user data could be weaponized against us, with the past few years only serving as the beginning of it.

In a statement by the Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, he mentions that The United States would welcome the use of TikTok if it were to be sold to an American company. This would eliminate the possibility of the Chinese government legally gaining access to user data under their country’s National Intelligence Law. This solution, however, is and should not be comforting to the average American resident. Many privacy concerns that still exist today have nothing to do with foreign controlled applications. In fact, the Cambridge Analytica scandal referenced in The Great Hack happened as a result of data privacy breaches in American company, Facebook. Still, this information had the ability to tamper with the 2016 United States election in ways Americans did not have the ability to consent to.

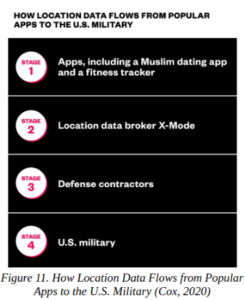

Today, there are still plenty of legal ways U.S. military and domestic companies may exploit consumer data. In a recent report detailed by Vice news, the US military buys location data from specifically Muslim targeted app in an attempt to track and identify Muslim users in the United States and abroad. This includes apps like Muslim Pro, an app that reminds users when to pray; Muslim Mingle, a social appp for connecting people of faith; as well as country focused social ap ps like Iran Social, Turkey Social and Egypt Social to name a few. All of this is completely legal and done with the help of “data brokers” like X-Mode Social. A data broker is a business that quietly buys and sells user data, connecting information bought from consumer data companies and selling it as a product or service for companies or individuals to use (Beckett, 2014). In the case of X-Mode Social and The United States Military, the data broker will buy data sold to them by apps like Muslim Pro and license the access of this data to government contracted defense companies. While data sold by data brokers comply with privacy laws by making the data itself anonymized, it is completely possible for this data to be anonymized given the immense amount of data available on the internet already.

ps like Iran Social, Turkey Social and Egypt Social to name a few. All of this is completely legal and done with the help of “data brokers” like X-Mode Social. A data broker is a business that quietly buys and sells user data, connecting information bought from consumer data companies and selling it as a product or service for companies or individuals to use (Beckett, 2014). In the case of X-Mode Social and The United States Military, the data broker will buy data sold to them by apps like Muslim Pro and license the access of this data to government contracted defense companies. While data sold by data brokers comply with privacy laws by making the data itself anonymized, it is completely possible for this data to be anonymized given the immense amount of data available on the internet already.

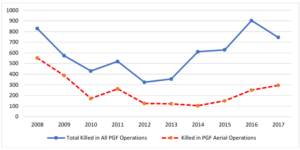

Figure 12. Afghan Civilians Killed by Pro-Government Forces, 2008-2017 (Crawford, 2018)

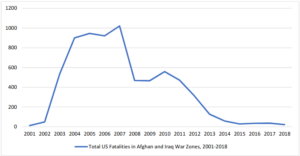

Figure 13. Total US Military Fatalities in Afghanistanand Iraq War Zones, 2001-2018 (Crawford, 2018)

The United State’s emphasis on li miting the control of Chinese owned apps comes across as contradictory when looking at how the U.S. itself benefits from the mined data of American owned apps. Navy Cmdr. Tim Hawkins, a U.S. Special Operations Command spokesperson, confirmed the purchase of mined data from companies like X-Mode Social while adding “Our access to the software is used to support Special Operations Forces mission requirements overseas. We strictly adhere to established procedures and policies for protecting the privacy, civil liberties, constitutional and legal rights of American citizens.” (Cox, 2020) Here, it is clear that the military buys consumer data in order to influence and inform decisions that happen abroad. Given the loosely defined privacy laws in the United States, there is now doubt that the use of this data by the U.S. military is legal, but the ethical implications far too often go unexplored. With many of the users in the data supply chain being Muslim, it raises concerns on exactly how the data obtained from these data brokers are being used to perpetuate violence given that the United States has upheld a decades-long war in the Middle East, looking to target Muslim terror groups. In 2014, a former drone operator for the military’s Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) confirmed that they would often identify targets based on metadata analysis and cell phone tracking technologies. They mention “It’s really like we’re targeting a cell phone. We’re not going after people – we’re going after their phones, in the hopes that the person on the other end of that missile is the bad guy.”(Scahill, 2014) It is evident that the use of location, phone and user data is being used to justify the use of drone strikes in military operations abroad. The unintended consequences of this is the increased death of civilians as a result of inaccurate data analysis that has been used to approve the attacks. Figure 12 shows a steady increase of civilians killed by aerial operations while Figure 13 shows U.S. military deaths to be less than civilians killed in aerial operations over the between 2014 and 2017. It’s clear that a once American priority to minimize the collateral damage of innocent life is quickly fleeting as we begin to rely on inaccurate data driven drone strikes to fight our wars and track down enemies. By now, it is clear the U.S. not only needs to reevaluate their use of drone strikes, but the ethics of using the mined data from people of Muslim faith in order to justify them.

For more information on social media and privacy please click here.