While Section I outlines the reasons the college should invest in this issue on an institutional level, further incentive to purse the aforementioned waste reduction measures are provided on a student level. The college takes great pride in responding to student needs, particularly within dining services. Students participate in dining surveys and on the Food Services Advisory Committee, while additional input is received through communications with Student Government and through individual complaints and requests (P. McLoughlin, personal communication, February 13, 2017). This level of responsiveness to student demands indicates that the college will respond to a call for waste reduction if it comes from the student body. Through a survey that I conducted for this report in April, 2017, it is clear that the issue of food waste is both salient and intense within the student population.

Lafayette currently has very little quantitative or qualitative data regarding food waste. I conducted a survey about food waste in order to gage awareness of the issue on campus, understand self-assessed behaviors, and to identify areas of concern for students that may be useful in develop future awareness campaigns for food waste reduction. While the results of this survey can be used to understand the issue from the student perspective, it is important to note that student responses are subjective and cannot be used to accurately measure the amount of food students waste. I developed a 10 question survey submitted to and approved by the International Research Board. I distributed this survey to students outside of the two buffet-style dining halls, Marquis and Upper Farinon, during lunch periods. A total of 104 completed surveys were gathered and statistically interpreted.

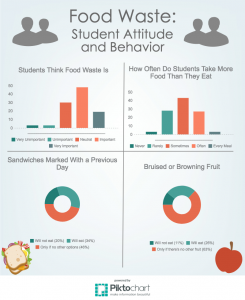

This interpretation yielded information about how aware students are about food waste and how they self-report their own waste behavior. Results for the survey question asking students how often they think about food waste indicate a positively skewed normal distribution, with students thinking about food waste “sometimes” to “often” on average. However, students appear to be aware of the concept of “food waste” to a much higher degree than they are cognizant of their personal waste, with 96% of students reporting that they have heard of food waste. When comparing this awareness to behavior, it appears that students are slightly less likely to waste food than they are to think about wasting food. When asked “How often do you take more food than you eat?”, student responses showed a normal distribution with the highest percentage of students reporting that they “sometimes” take more food than they eat.

While this assessment of waste behavior in self-serve facilities is useful in determining how often portion control causes waste, other factors play a role in waste behavior within grab-and-go facilities. When asked if they would eat a sandwich from a grab-and-go station labeled with a previous day, the greatest number of students (46%) responded that they would eat those sandwiches, indicating that students are less likely to waste food based on labeling than they are when putting food on their plate. However, during the survey distributions, several students expressed their confusion on whether or not these labels indicated best buy dates, expiration dates, or date of preparation. This confusion may have led to multiple interpretations of the question. Furthermore, while nearly half of respondents reported that they would eat the sandwich, 34% reported that they would only eat the sandwich if there were no sandwiches marked for the current day and 20% indicated that they would not eat the sandwich. Projecting results onto the entire population of 2,450 students (Lafayette CollegeA), that would mean that 833 students would only eat the grab-and-go sandwiches under certain conditions, and 490 students would not eat these sandwiches.

Looking at waste behavior as it applies to fruit, a key staple in grab-and-go meals at Lafayette, results indicate that appearance is a substantial factor in fruit selection with 63% of students who would only eat bruised or browning fruit if no alternatives were available and 11% of students who would not eat bruised or browning fruit in any circumstance. Given the fluctuations of students at dining facilities, the high consumer standard indicated by survey responses, and the retail perspective that demands that dining facilities maintain fully stocked appearances, it is likely that a significant portion of this fruit is sent to the landfill, even without quantitative evidence to track the waste.

These self-assessed behaviors are key to understanding the student mindset surrounding food waste. Understanding where and for what reasons students waste food offers a platform for future education initiatives. Sharing information with students about food labeling would clear confusion surrounding “best buy” dates. If students are educated and reminded about these issues, it would become more acceptable for Bon Appetit to only stock grab-and-go meals and fruit that are nearing or past their sell by dates. Students who currently only eat sandwiches past their best buy dates or eat bruised or browning fruit if no alternatives are available, would then be encouraged to purchase these foods. In self-serve facilities, hanging posters to encourage students to be mindful of plate waste or providing smaller plates could reduce plate waste. In the Spring of 2017, an awareness and data collection campaign entitled “Weigh the Waste” was conducted in campus dining halls. Volunteers stood in front of the disposal windows, directly collecting plate waste from students in clear, plastic containers which were then weighed at the end of the meal period. The data collected from the two separate weeks in which waste was weighed indicates that simply making the waste visible can impact behavior. Between the first weighing in March and the second weighing in April, a 2% reduction in student plate waste was recorded (M. Fechik-Kirk, personal communication, April 26, 2017).

These education and awareness campaigns would be most effective if they catered to broader interests. Students were asked to identify how much they care about certain issues listed in my survey that fell into the categories of “environmental”, “social”, and “economic.” Responses indicated that students at Lafayette are most invested in social issues, followed by environmental, and then economic. Given this information and the knowledge that food waste is tied to issues within all three of these categories, a campaign that emphasizes social issues connected to food waste, such as hunger and poverty, may be the most effective means of encouraging students to change their consumption behaviors.

While encouraging students to alter their behaviors can be effective, it cannot be the only solution. The administration must also take action and the survey results indicate that it is in the students’ interest to do so. On average, students feel that the issue of food waste on campus is “important” and the aforementioned education and awareness campaigns may serve to further increase the intensity of student investment in this issue. Moving forward, the administration should consider food waste as an important issue on campus and prioritize infrastructure that will reduce its creation.