The full report can be found here: Lafayette Report

In a society overwhelmed by environmental crises, economic hardships, and social injustices, it can be difficult to identify what actions to take. We are often mired in the confusion, unable to pinpoint what issues to tackle. However, certain challenges are within the scope of our control, as in the case of food waste. Food waste, or the “wholesome edible material intended for human consumption, arising at any point in the [food supply chain] that is instead discarded, lost, degraded or consumed by pests” (Papargyropoulou et. al, 2014), is a product of the food systems we have built and is therefore susceptible to manipulation. Understanding of the consequences of wasted food, which include environmental, economic, and social repercussions, is beginning to spread beyond the scientific community. With this spread of knowledge comes a directive for action.

EPA Food Recovery Hierarchy

Existing resources, such as the EPA’s food waste hierarchy, offer means to inform food waste solutions. The food recovery hierarchy, as depicted in Figure 1, categorizes solutions into 6 tiers. These categories are then ranked, with the top of the pyramid identifying the most favorable solution and the bottom of the pyramid identifying the least favorable solution. Landfills, as an emitter of methane, represent a “last resort” for food disposal. Moving up the hierarchy, composting offers a more sustainable and environmentally beneficial outlet for waste, repurposing food to fertilize the production of more food. Industrial use offers the opportunity to transform waste into energy, replacing traditional CO2 emitters like oil. The next two tiers of the pyramid recommend redirecting food that would be wasted to other consumers such as animals and food insecure individuals. Finally, the most favorable option of the food waste hierarchy is source reduction, which eliminates the production and distribution of excess food. These alternatives to food disposal can inform decisions made within local, national, and international food systems.

Lafayette College, as a microcosm of the United States, can serve as a model for food waste reduction if the necessary actions are taken. In order to discover the most efficient paths forward, I have compiled a four-piece compilation of information, recommendations, and tools for future work. Firstly, the report following this introduction provides a literature review of existing knowledge and research on food waste with specific attention to the context of the food system at Lafayette College. The literature review also details reasons for food waste, consequences of waste, and broad recommendations for waste reduction. This information serves as a platform for the analysis of food waste at Lafayette that follows. The section of the report dedicated to Lafayette highlights why the Lafayette community should take action, both on an institutional level and a student level, existing infrastructure, and opportunities for waste reduction. This report also details the results of a qualitative student survey I conducted in April, 2017 which illuminates student interest in food waste and self-reported waste behaviors. The report concludes with recommendations for future action, prioritized in accordance with the EPA’s food waste hierarchy.

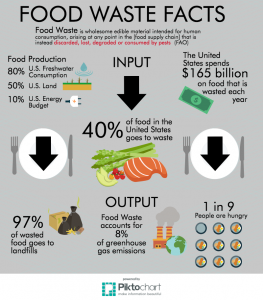

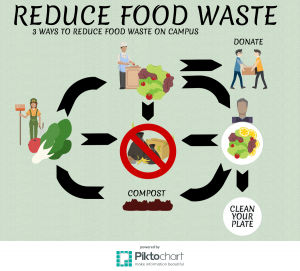

The second and third pieces of this project provides tools to raise awareness about food waste through different forms of media. Using data collected from my survey, research gathered for the report, and my own conclusions, I created 4 infographics for educational purposes [Food Waste Facts, Reduce Food Waste, Student Attitudes and Behaviors, Food Waste Actors]. The third component of the project consists of a short 2-and-a-half-minute video to raise awareness about food waste on Lafayette’s campus. The video consists of interviews with Marie Fechik-Kirk, Lafayette’s Sustainability Director, Bonnie Winfield, Lafayette’s Director of Community Partnerships, Haley Mauriello, a student leading a food recovery initiative on campus, and Sarah Edmonds, the manager of LaFarm. With accompanying footage of campus kitchens, dining facilities, LaFarm, interviews with students, and other visual aids, the video seeks to offer a brief and direct explanation of what food waste is, why it is an issue, and what Lafayette can do about it as a community.

The fourth and final piece of the project is this website to compile the report, infographics, and video. The website provides an organized and visually appealing format for consuming these materials and allows for long-term access to these resources.

The goals of this project are to provide a synthesis for all projects, people, and infrastructure related to food waste at Lafayette, tools for raising awareness, and informed recommendations for future action and research. The products of this study should be consumed with the knowledge that making Lafayette College a zero-waste institution is not an abstract concept. I conclude that the recommended actions are feasible and that the College has a responsibility to its mission and to its community to take these steps towards food waste reduction.

Consequences of Food Waste:

While the pervasiveness of the issue may daunt the average consumer, the consequences of continuing this behavior indicate the need for immediate and direct action. From an environmental perspective, food waste is synonymous with the waste of land, water, and energy resources (Papargyropoulou et. al, 2014). In the United States, the production of food accounts for 50% of U.S. land and 80% of the country’s total freshwater consumption (Gunders, 2012). Furthermore, the growth of food is also harmful to biogenic cycles (Papargyropoulou et. al, 2014) with approximately 28 million tons of fertilizer applied to food that is ultimately wasted (Lipinski et al., 2013). Pollution from food waste can also be measured in the amount of methane produced by its decomposition in landfills (EPA). With these massive amounts of wasted resources and pollution, it is unsurprising the food waste contributes approximately 8% of annual greenhouse gas emissions (Johnson, 2017). A report published by Champions 12.3, asserts that “if food waste were its own country, it would be the third largest emitter of such gases in the world, after China and the U.S (Johnson, 2017).

Economic resources are also wasted as food is wasted. On the production end of the food supply chain, food takes up 10% of the U.S. energy budget. For the average American consumer, annual food waste costs around $1,600 per year for a family of four (Lipinski et al., 2013). Considering all of the costs of input by actors along the food supply chain, the United States spends approximately $165 billion dollars each year on food that is wasted (Plumer, 2012). Companies in the food industry are beginning to realize the cost of their food waste and are financially benefiting from efforts to reduce this waste, earning more than a “14-fold return on investment in food waste reduction” (Johnson, 2017). In addition to costs in the production, distribution, and consumption sectors of the food supply chain, economic costs also exist at the disposal level with massive investment in landfills (Hirshfeld et. al, 1992). Landfills not only require funds to construct and maintain, but also decrease nearby property values (Hirshfeld et. al, 1992). Furthermore, using land for waste disposal has notable opportunity cost in that the land cannot be developed or preserved in its natural state (Hirshfeld et al., 1992).

In addition to environmental and economic consequences, food waste also instigates social injustice and a failure in the food supply chain. Roughly 1 in 9 people in the world suffer from hunger (Hunger Notes, 2016b). In the United States, 12.7% of households are food insecure, meaning that they lack reliable access to food (Hunger Notes, 2016a). Yet 40% of food in the U.S. goes to waste (Gunders, 2012), highlighting the current food system’s ability to make food accessible. While food redistribution remains a topic of interest for those seeking to reduce waste, the paradox of excess food production coexisting with undernourishment continues to persist.