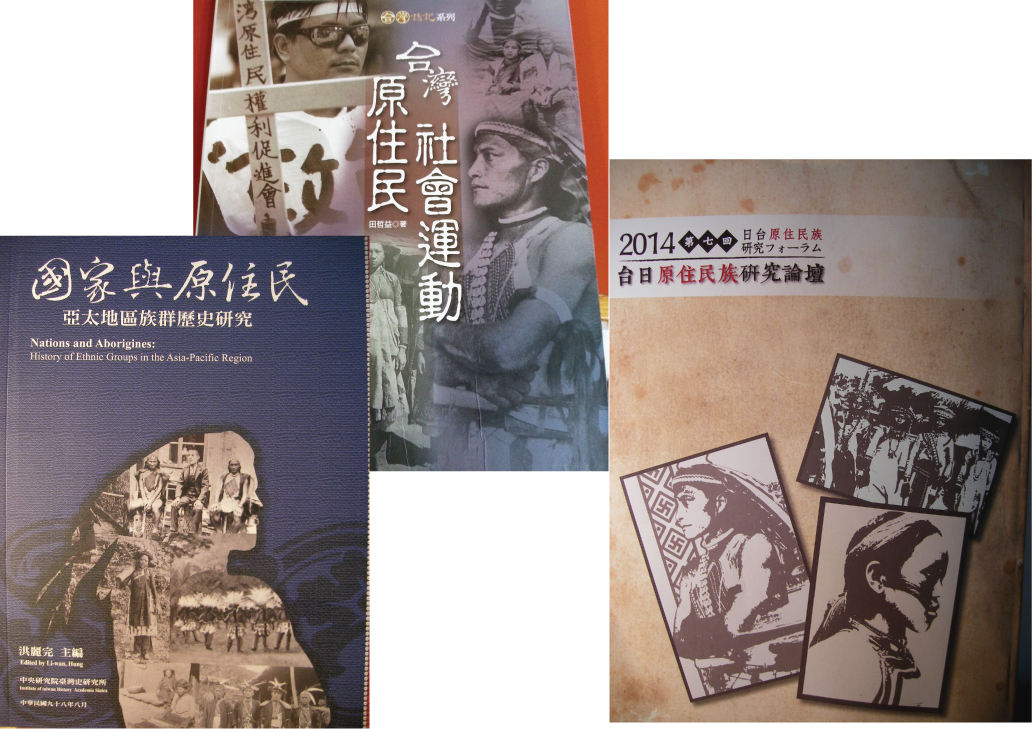

These three recent book covers all feature graphics based on a photograph that first appeared in the June, 1935, issue of Riban no tomo 「理蕃の友」(page 3). From left to right, they were published in 2009, 2010, and 2014 [1]. The third publication is a collection of conference papers from the 7th Japan-Taiwan Forum for Research on Indigenous Peoples held at Chengchi University, Taipei, on October 12, 2014 (国立政治大学に開催さらた 2014第七回日台原住民族研究フォーラム).

These three recent book covers all feature graphics based on a photograph that first appeared in the June, 1935, issue of Riban no tomo 「理蕃の友」(page 3). From left to right, they were published in 2009, 2010, and 2014 [1]. The third publication is a collection of conference papers from the 7th Japan-Taiwan Forum for Research on Indigenous Peoples held at Chengchi University, Taipei, on October 12, 2014 (国立政治大学に開催さらた 2014第七回日台原住民族研究フォーラム).

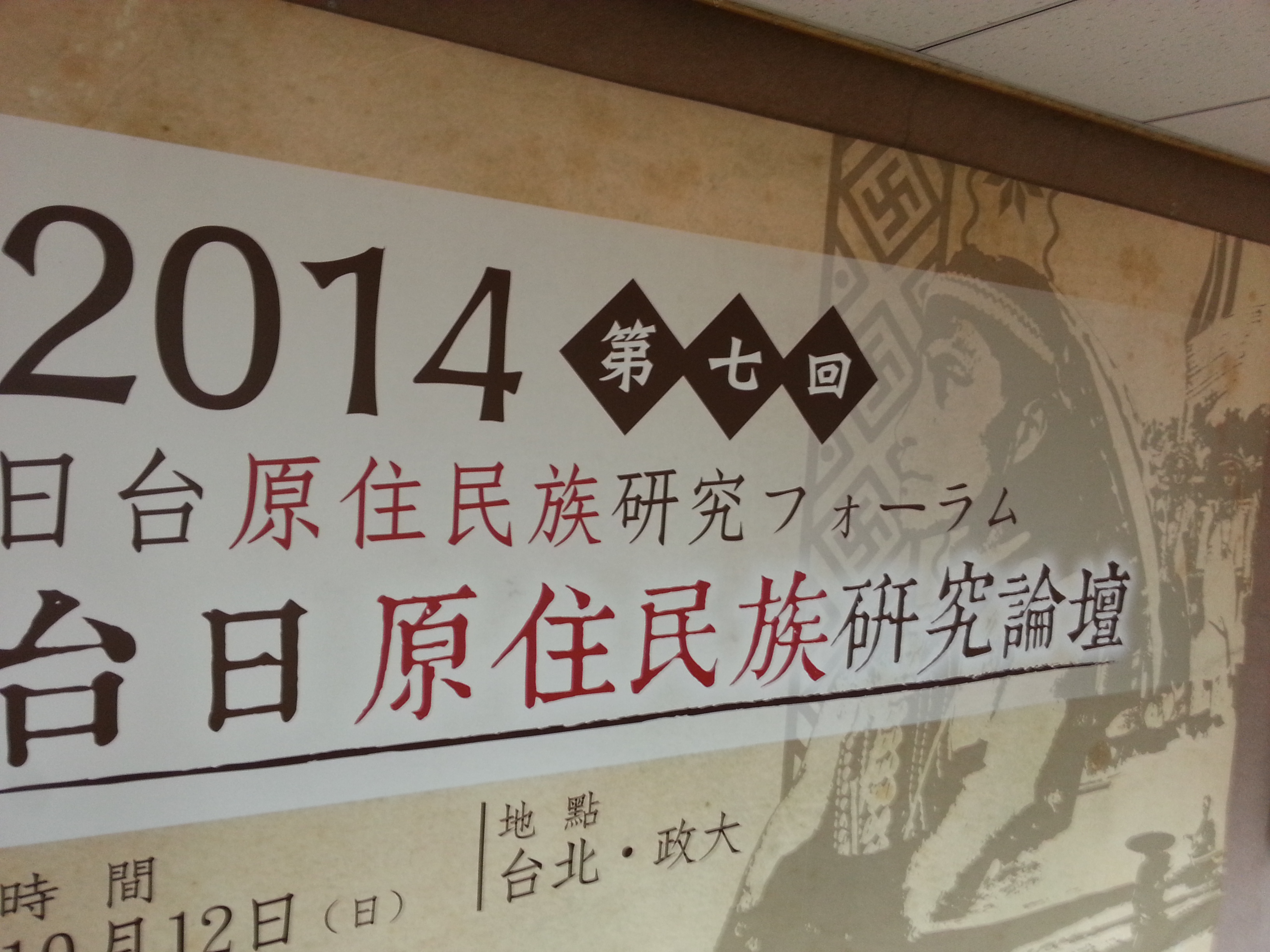

This image was the backdrop to all of the panels at Chengchi University:

For a full day, I stared at this image and wondered where it came from, and what its life history has been as a symbol of Tsou/Zou/鄒 peoples, or all Taiwan Indigenous Peoples.

For a full day, I stared at this image and wondered where it came from, and what its life history has been as a symbol of Tsou/Zou/鄒 peoples, or all Taiwan Indigenous Peoples.

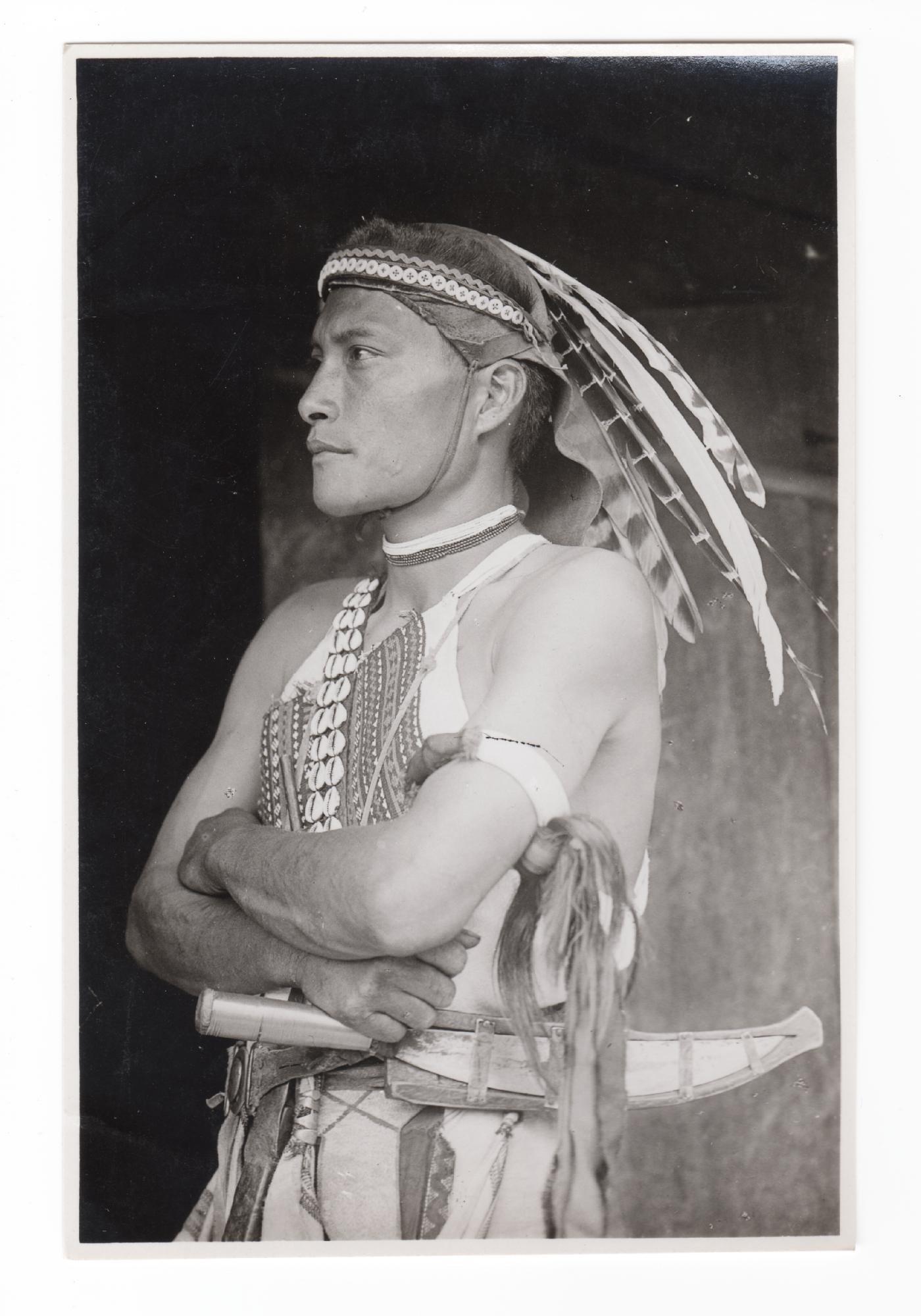

Though his image appears on the walls of a national museum (in Nantou), in the pamphlets of an esteemed anthropology museum (in Taipei), in educational materials (in Yilan), and on several contemporary book covers, he has remained anonymous, as if his name has been forgotten. His name is even missing from the several contemporary documents (mostly postcards) reproduced below. Nonetheless, this individual’s family is still around and they recognize him. His name is yapasuyongu voyuana. He lived in Tfuya (トフヤ, 特富野) near Alishan (or Arisan), and was born in 1904 into the voyuana clan, which is a cadet branch of the yaisikana clan. His son yavai voyuana was born in 1929 and took the Japanese name Ishikawa Hikaru. Both men are now deceased, though yapasuyongu voyuana lives on as the subject of this famous photograph.

These biographical facts have come to light thanks to Professor Miyaoka Maoko, who kindly made inquiries on my behalf to yapasuyongu’s grandson, who is part of a kin network Professor Miyaoka entered during her several years of fieldwork in Jiayi Province. Professors Kasahara Masaharu and Nobayashi Atsushi, along with Professor Miyaoka, attended the forum mentioned above, and have also generously shared their knowledge of yapasuyongu’s family and Tsou lineage politics with me.

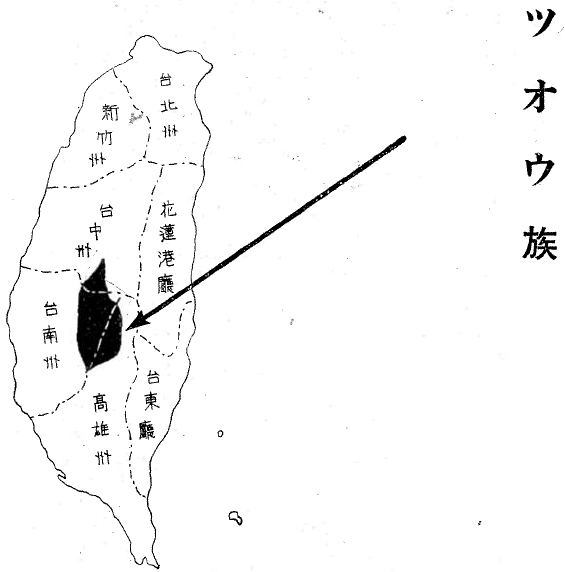

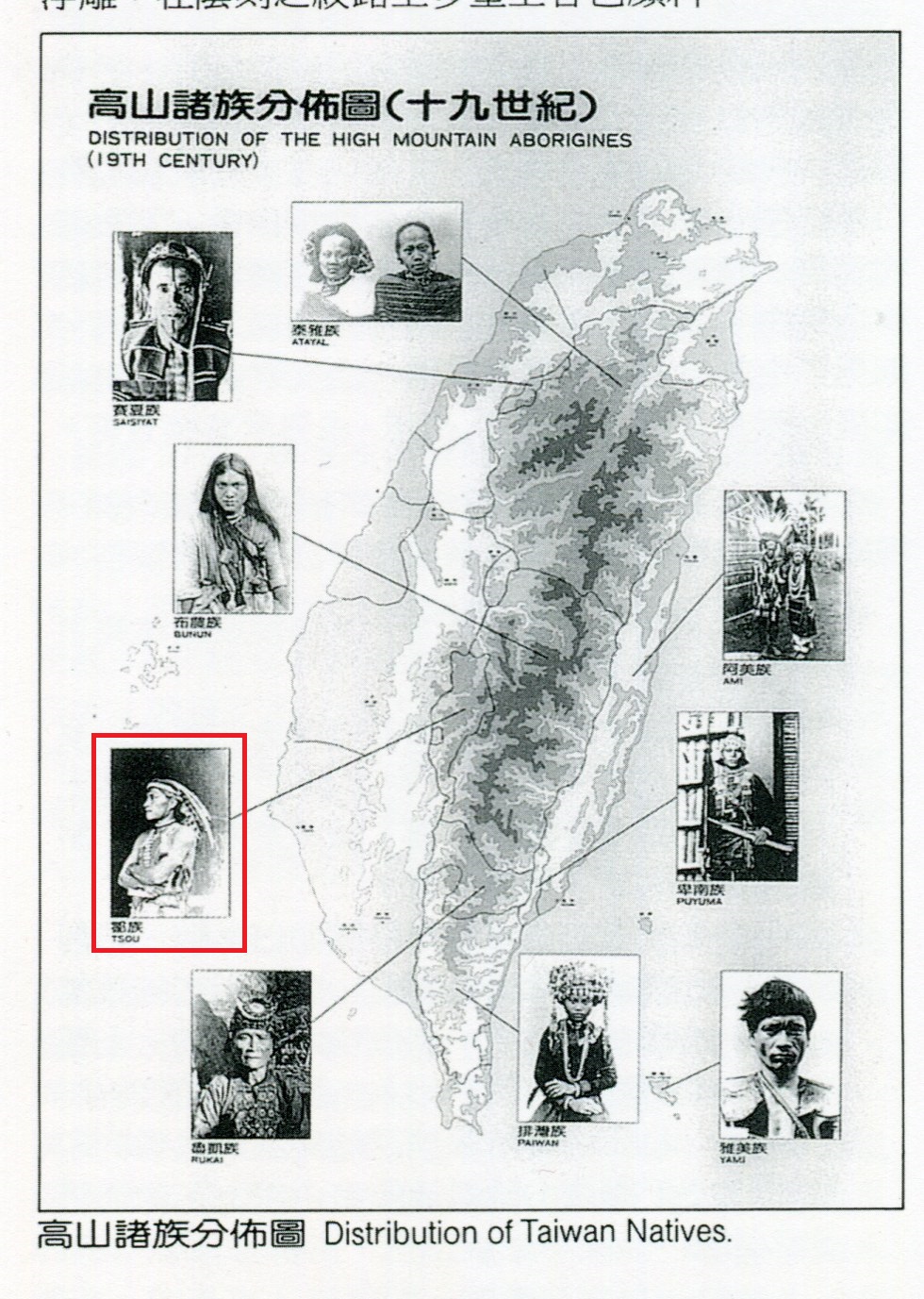

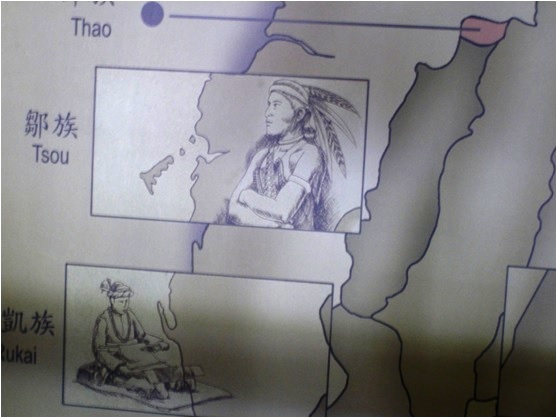

The photographer was either Segawa Kokichi or Katsuyama Yoshisaku. Both of these men produced hundreds of commercially successful portraits of Indigenous Peoples in the 1930s in the colony of Taiwan. Since this photo was published as a Katsuyama Studios postcard, and was also published in the exhibition catalog for the 1935 Taiwan Exposition, one of these two photographers is likely to have taken the photo. Here is the part of Taiwan where the picture was taken, with the territory of the Zou (or Tsou) people marked out.

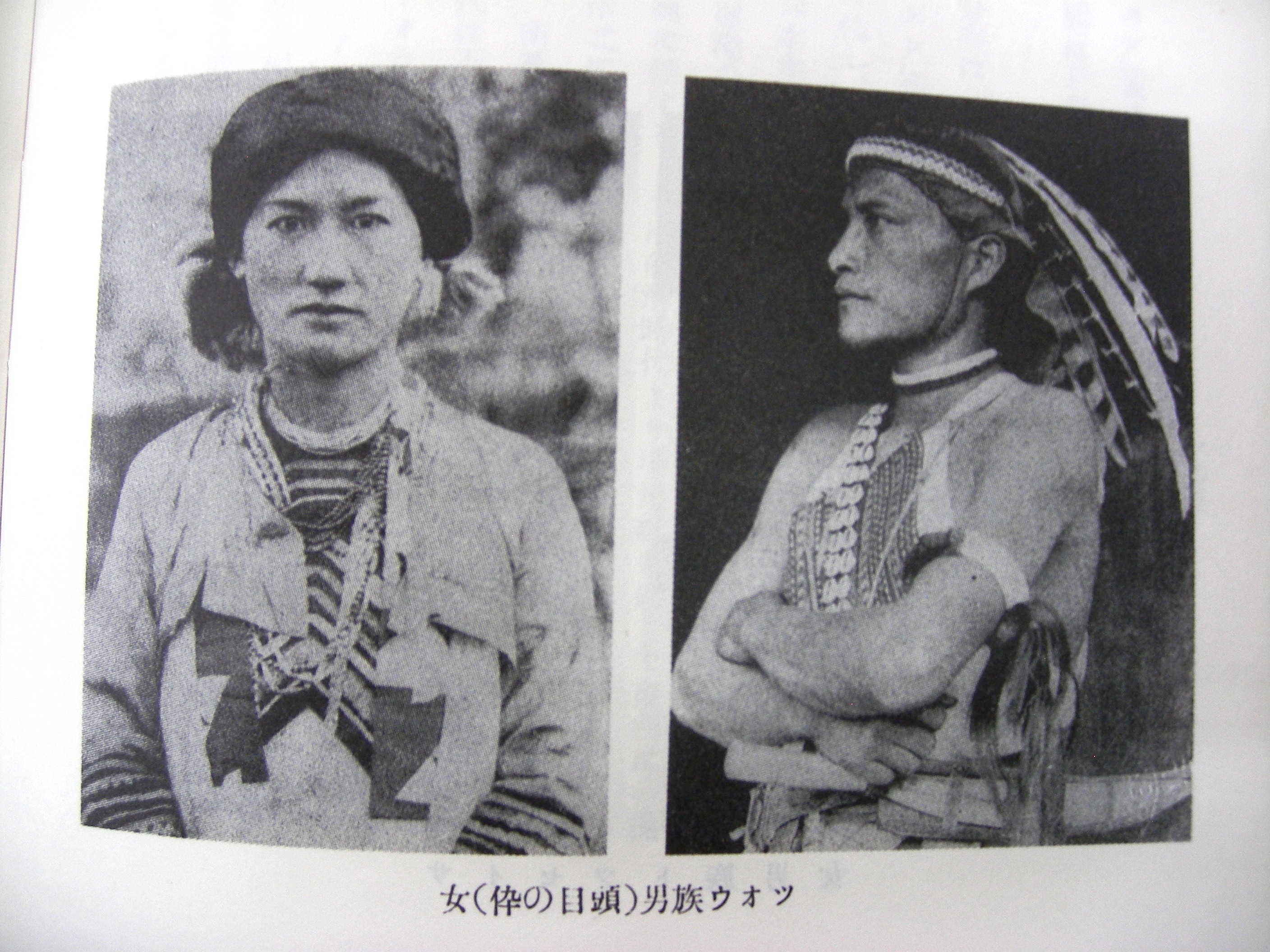

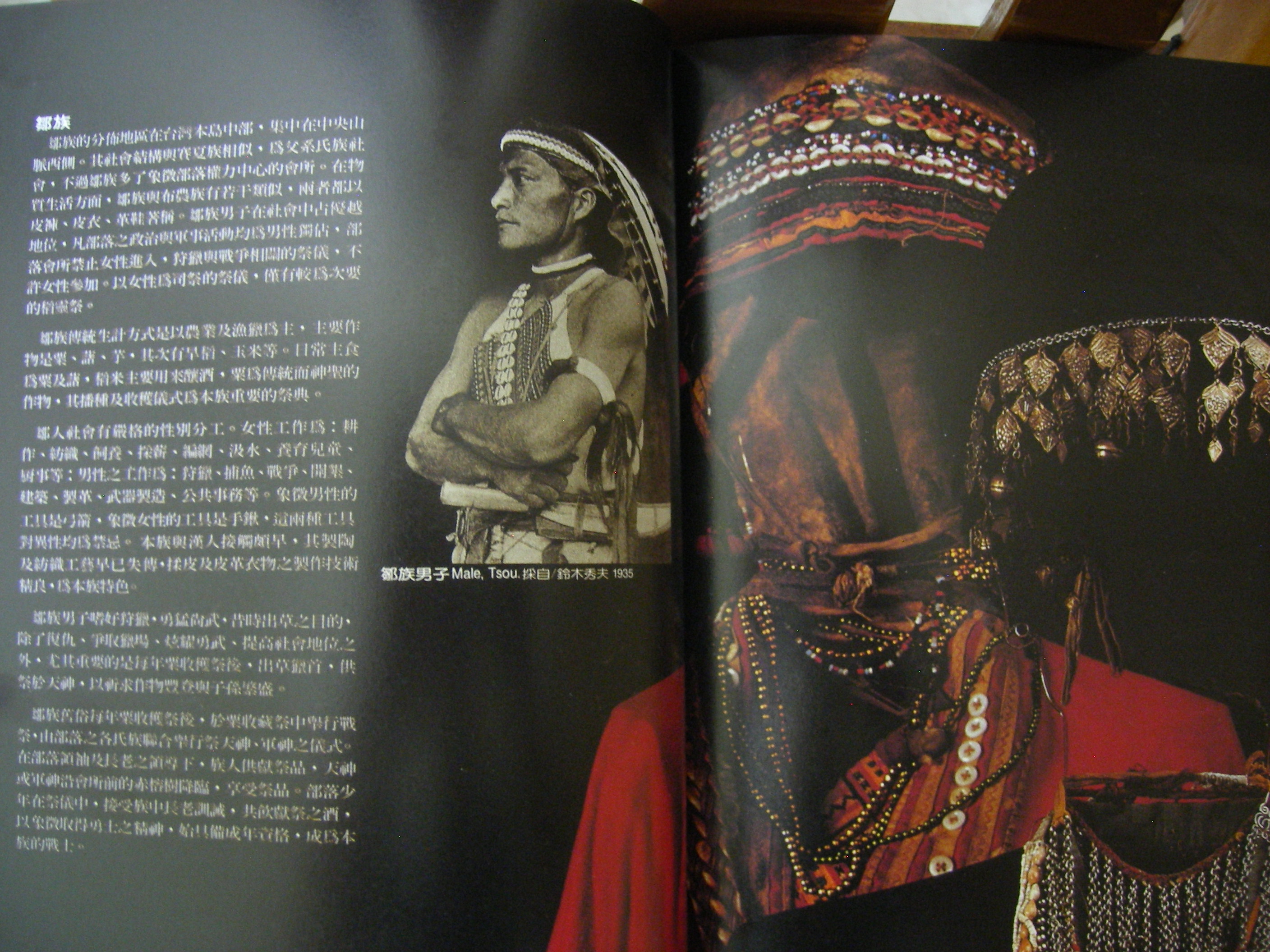

Suzuki Hideo 鈴木秀夫 (ed.) Taiwan bankai tenbo 台湾蕃界展望 (Taipei: 理蕃の友, 1935), p. 46.

Suzuki Hideo 鈴木秀夫 (ed.) Taiwan bankai tenbo 台湾蕃界展望 (Taipei: 理蕃の友, 1935), p. 46.

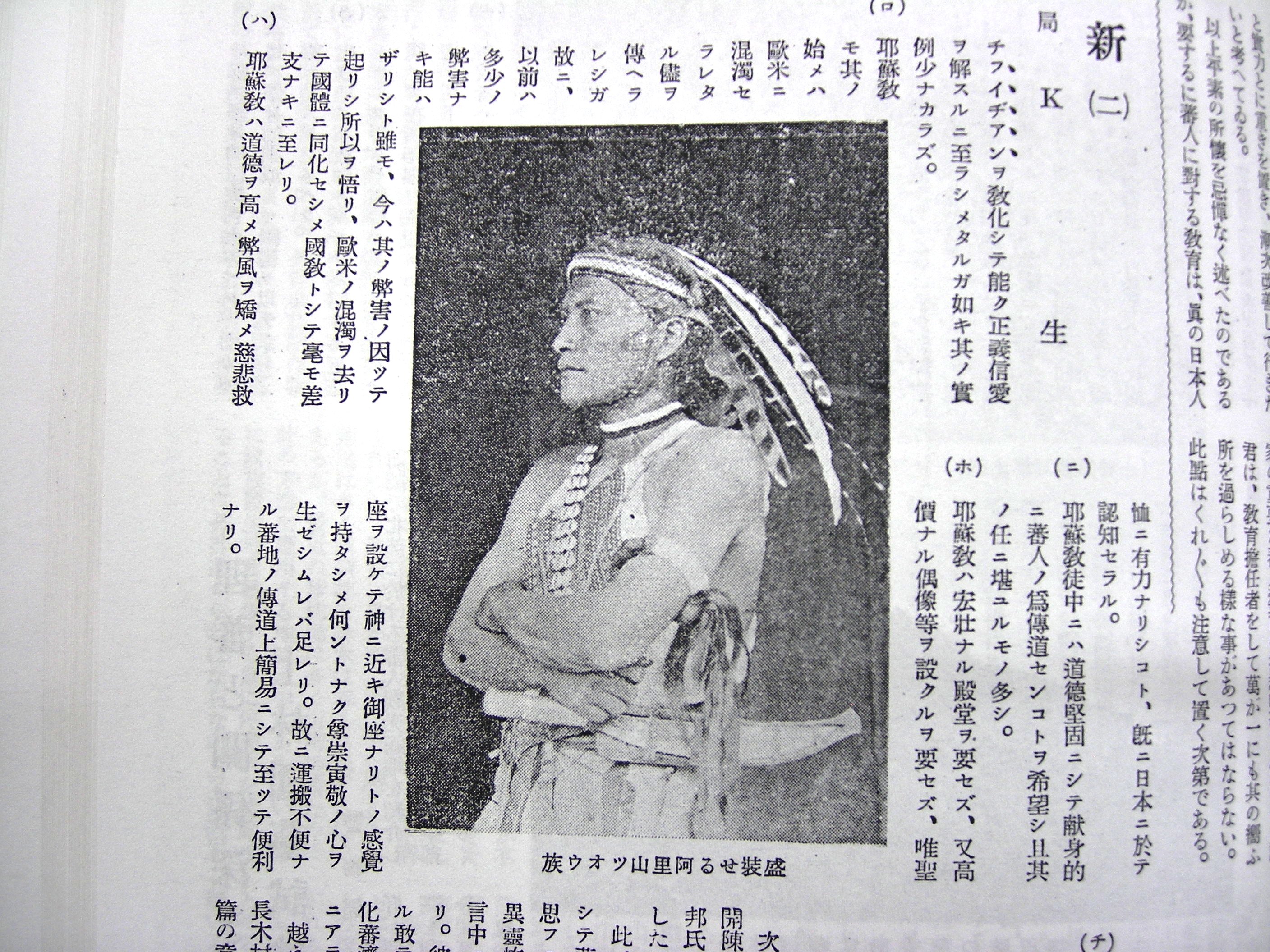

The first appearance of yapasuyongu’s portrait that can be dated with certainty is June 1st, 1935. The magazine it appeared in, Riban no tomo, was published for Japanese policemen who worked in Taiwan’s “Aborigine District.”

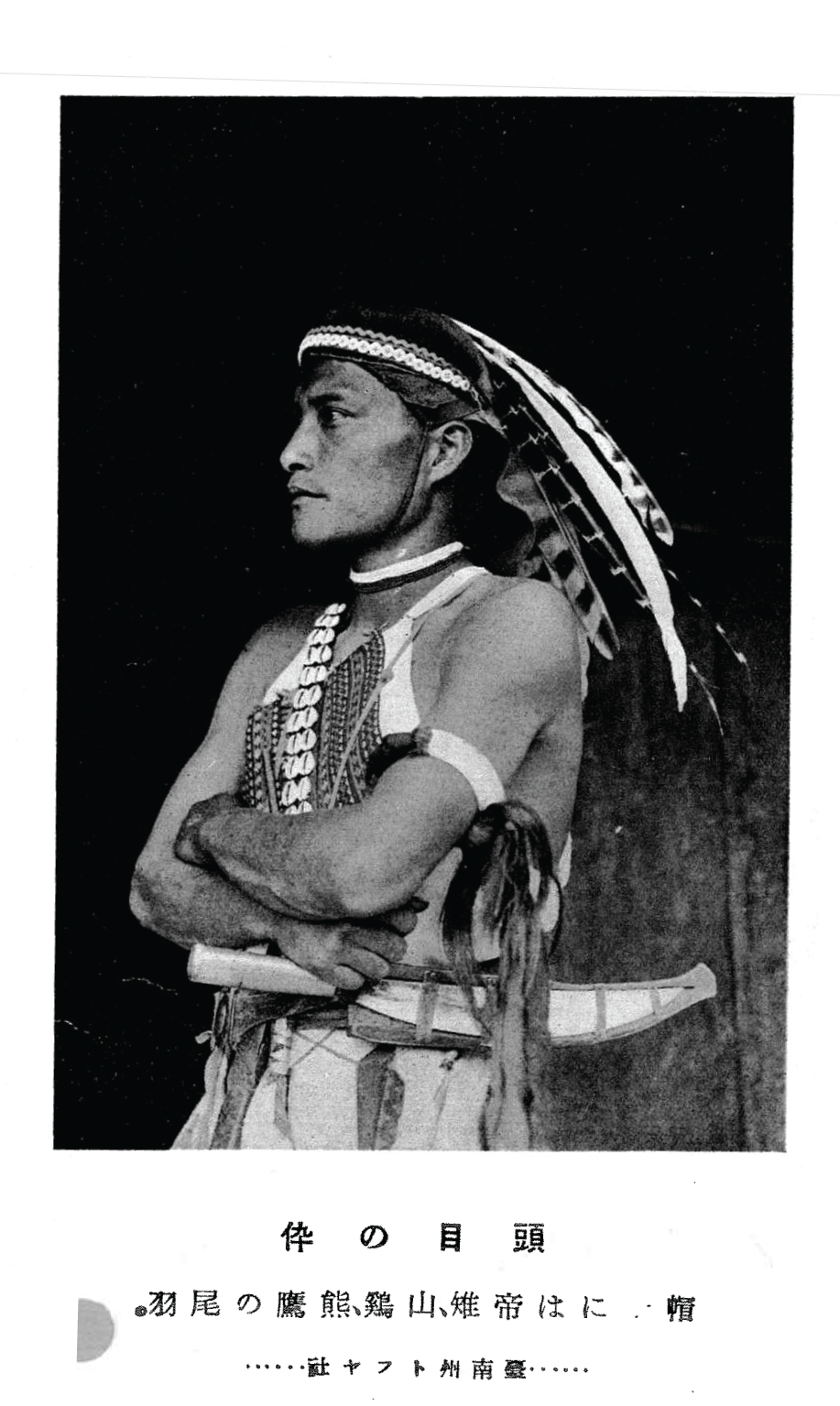

『理蕃の友』 June 1st, 1935, p. 3.

『理蕃の友』 June 1st, 1935, p. 3.

In this instance, the photo is not connected to the text, but is just a decoration. The photo is surrounded by an article about Indigenous Peoples’ religious reforms. The caption merely mentions that yapasuyongu is an Alishan Zou tribe person in costume (though his name is not indicated). Riban no tomo was founded by Suzuki Hideo, who was also the editor of a photo album that was sold as part of the 1935 Taiwan Exposition (see below). This event attracted well over a million visitors. The photo album’s arrival was eagerly anticipated in the pages of Riban no tomo; the advertisement was an elaborate full-page affair. The album, pictured below, was published on November 3, 1935:

『台湾蕃界展望』

As advertised, each portrait in this album included a descriptive caption that provided facts about the people in the pictures:

Suzuki Hideo 鈴木秀夫 (ed.) Taiwan bankai tenbo 台湾蕃界展望 (Taipei: 理蕃の友, 1935), p. 50.

Suzuki Hideo 鈴木秀夫 (ed.) Taiwan bankai tenbo 台湾蕃界展望 (Taipei: 理蕃の友, 1935), p. 50.

The caption does not provide us with a personal name (these were avoided in this album), and describes yapasuyongu as a “chief’s son” or “vice chief” 頭目の伜 from Tfuya in Tainan. The caption puts equal textual emphasis on his hat, which sported tail feathers of the “Imperial Pheasant (帝雉), Mountain Chicken (山鶏), and a Hawk Eagle (熊鷹).

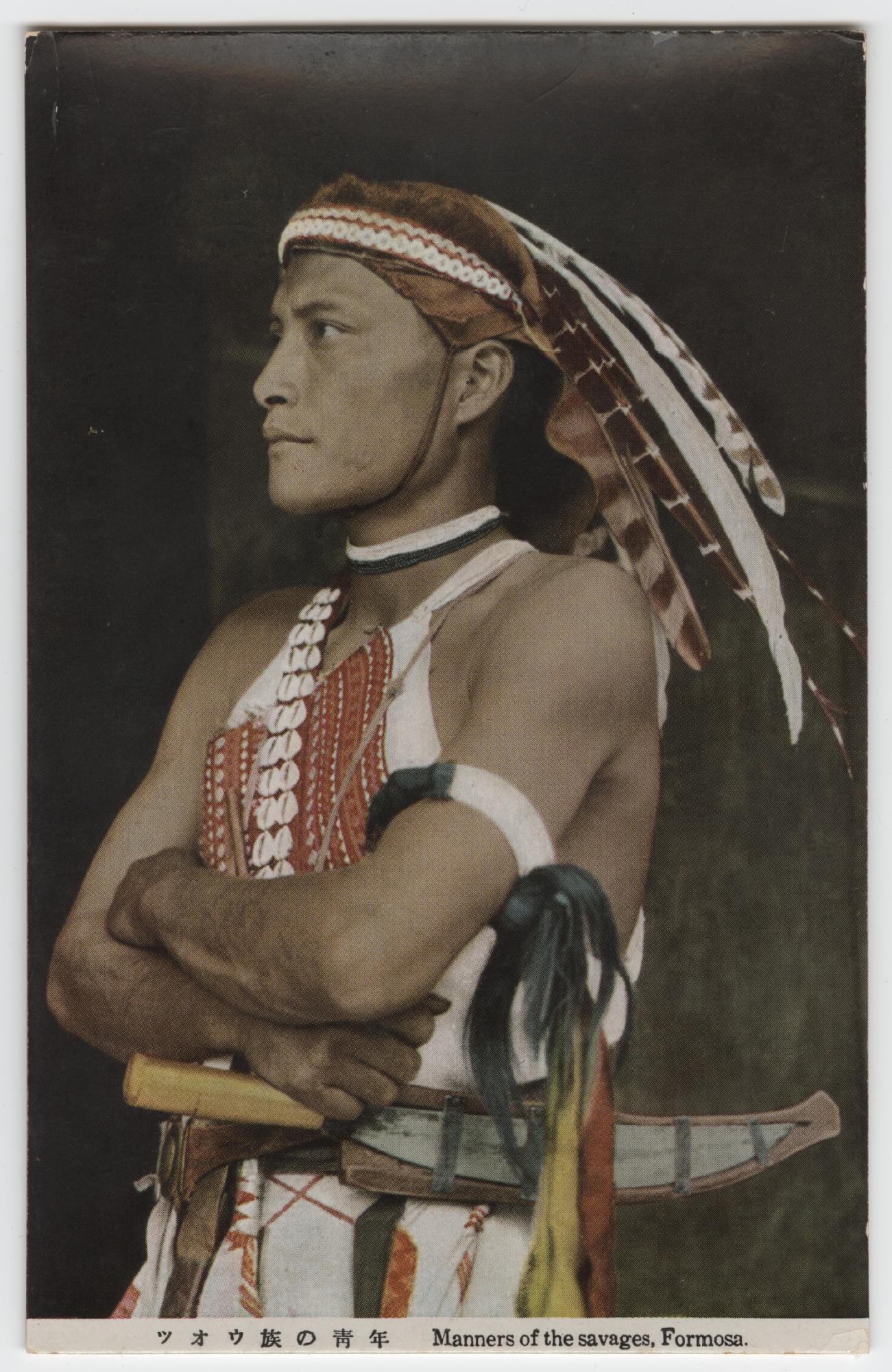

Soon after the exhibition, this photo was turned into a Katsuyama Studio picture postcard:

[wa0327] [Tsou chief] ツオウ族の青年 Manners of the savages, Formosa

[wa0327] [Tsou chief] ツオウ族の青年 Manners of the savages, Formosa

This color postcard was most likely published in the mid- to late 1930s. We note that the caption is different from the one in the exhibition catalog: now the man is “youth” instead of a “vice-headman.” The National Central Library of Taiwan (国家図書館)has posted this same postcard, but has also supplied additional notes that indicate that this man was a chief’s son: 此人是鄒族特富野社(在今嘉義縣阿里山鄉)頭目之子,頭戴皮帽,帽上裝飾有帝雉、山雞尾巴的羽毛。

This postcard was also collected by Swiss Anthropologist Paul Wirz during his winter of 1936-37 trip to Japan, by journalist Harrison Forman in 1938, and by U.S. Consul to Taiwan Gerald Warner between August 1937 and early 1941. [2] In other words, anyone visiting Taiwan in the late 1930s was likely to pick up this card as either a souvenir or illustration of local “customs and manners.”

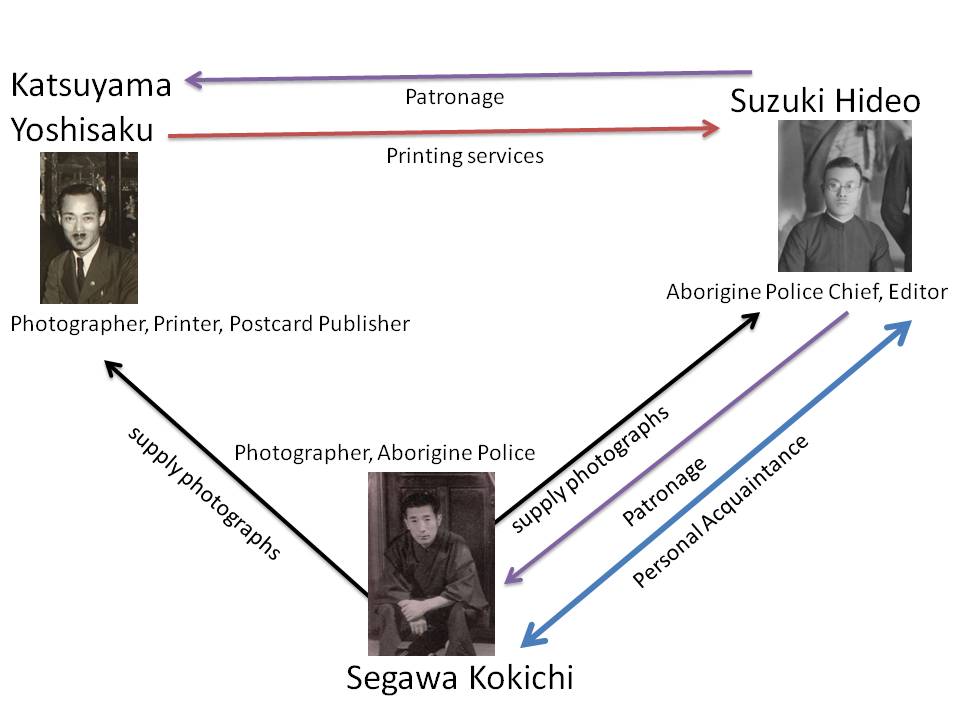

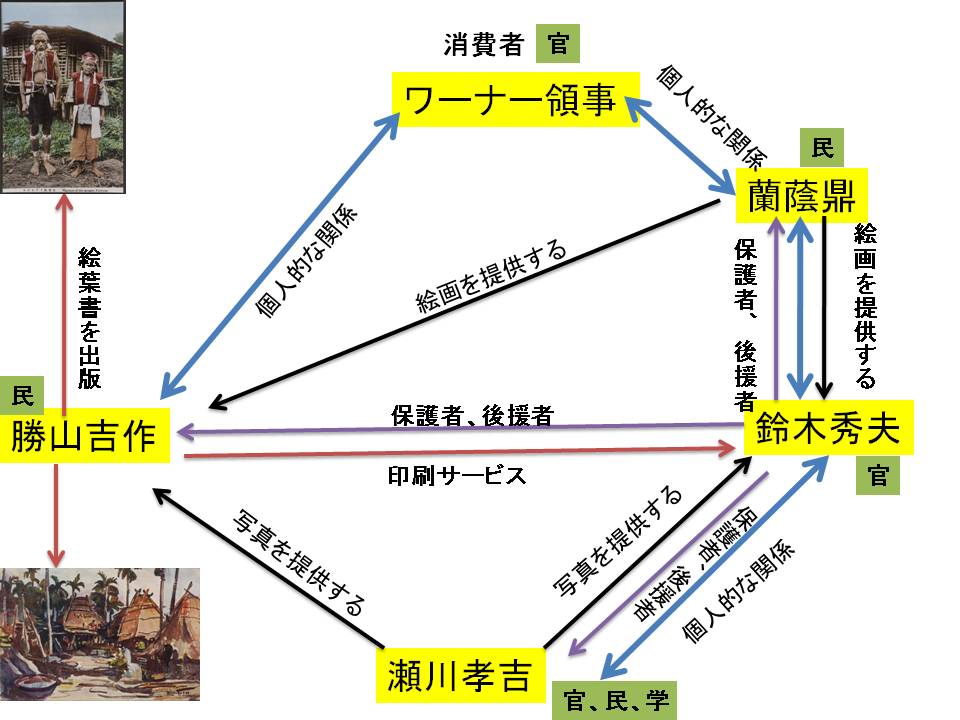

Due to the close connections between photographers, publishers, and colonial police in Taiwan, there was a great deal of overlap in content between the Exhibition album, the police magazine, and picture postcards; dozens of portraits were published in all three places. Here are two charts that map the relationship between postcard production, police work, and photography in 1930s Taiwan:

David Woodsworth, brother-in-law to the director of the McKay Hospital in Taipei (Donald Bews), also collected a print of the photograph as a souvenir during a fall 1940 visit to the island. The original appearances of this photograph in 1935 were in the low-quality Riban no tomo (an original copy in the Academia Sinica Institute for Taiwan History archives reveals the shoddy quality of the two-tone prints–they are grainy, dotted and display uneven distribution of ink) and the medium quality Taiwan Bankai Tenbo (which used half-tone printing, and not collotype). The Katsuyama postcards, and the print that Woodsworth collected, by contrast, have very good resolution and show that even the 1930s, postcards were still the medium for mass circulating high quality photographic images:

[ww0017] [Man in Leather and Feather Headdress with Large Knife]

[ww0017] [Man in Leather and Feather Headdress with Large Knife]

Ide Kawata reproduced this photo during this same period, in his massive tome A Record of Taiwan’s Administrative Accomplishments 臺灣治績志 in 1937. Ide followed the original caption from the 1935 companion to the exhibition. As was the case in the Aborigine Police organ, Ide’s use of the photo is decorative–there is no connection of the image to an individual, or historical event:

Ide Kawata, Taiwan Chisekishi (1937)p.190

Ide Kawata, Taiwan Chisekishi (1937)p.190

In the 21st century, yapasuyongu’s image continues to be used, and sometimes he is labeled a chieftan or war leader, and other times as a youth, but never by name. One souvenir knock-off, with a tri-lingual caption on the back, even includes contradictory information within the same item, describing its subject as a: 阿里山鄒族征帥/ツオウ族の青年/Zou commander”.

A recently published guide to the museum collection at the Institute of Ethnology at Academia Sinica (2007) displays his photograph both on its map of ethnic distribution as an example of Tsou clothing styles:

Lu Li-Cheng, ed. A Guide to Museum of Institute of Ethnology Academia Sinica (second printing 2007)

Lu Li-Cheng, ed. A Guide to Museum of Institute of Ethnology Academia Sinica (second printing 2007)

We can also find yapasuyongu’s image on a large wall map at the National Archives in Nantou, Taiwan (Taiwan Historica), again as an exemplar of an ethnicity:

In conclusion, we can say that yapasuyongu voyuana’s image, which is reproduced quite often today as a symbol of the Tsou/Zou people, or Taiwan Indigenous Peoples more broadly, had its origins in the 1930s network of policemen, photographers, and publishers. We can imagine that Mr. Segawa, or Mr. Katsuyama met him through an introduction from a local official or policeman. Soon after the photo was taken, it was quite widely propagated, though it did not commemorate a specific event, or the deeds of a specific person. Since the voyuana clan did not supply chiefs or headmen in Tfuya, the labels sometimes attached to yapasuyongu’s image are incorrect.

Surely, as many of the illustrations for this post indicate, yapasuyongu voyuana has become a symbol and a popular one at that. For those of us interested in the history of photography and colonialism, knowing his identity opens up new avenues for further research. Perhaps for his family, it is a good thing that someone took the trouble to learn his name. Whether the attachment of a name to the face diminishes the power or allure of this portrait is an interesting question, and another good topic for research.

Notes:

Corrections:

1) This post initially provided the name of the pictured man’s son yavai voyuana (b. 1929) as “Ishikawa Hakeru,” but it is “Ishikawa Hikaru.”

Acknowledgements:

Thank you to Professors Miyaokoa Maoko, Kasahara Masaharu and Nobayashi Atsushi for sharing their knowledge about yapasuyongu voyuana’s family and Zou culture, and for their encouragement of my research. Thanks to John Shufelt and Lin Shuchin for taking me to Nantou to visit Taiwan Historica. Research for this post was made possible by a Taiwan Ministry of Foreign Affairs research grant and the support of the Institute of Taiwan History at Academic Sinica. Special thanks to Professor Caroline Hui-yu Ts’ai for her guidance and support at ITH.

back [1] Nations and Aborigines: History of Ethnic Groups in the Asia-Pacific Region edited by Hung Li-wan (洪麗完) (Taipei: 中央研究院台湾史研究所, 2009);田哲益、『臺灣原住民社會運動』(臺北市 : 臺灣書房, 2010.10); 2014第七回日台原住民族研究フォーラム『日台原住民族研究論壇』

back [2] I have seen the card in Wirz’s and Warner’s collections; Forman scribbled what looks like descriptions of postcards in his notebook, one of which is a “profile of a big chief, TSUO,” which I take to be this card.

Leave a Reply