CRANE TELLS THE STORY

Wreck of Filibuster Commodore.

Graphic Description of the Sinking of the Vessel.

Account of the Voyage and Fatal Ending of the Expedition.

Some Humorous Incidents Connected With the Short Cruise.

Account of, the Novelist, Tells of His First Filibustering Venture.

Special to The Times-Democrat.

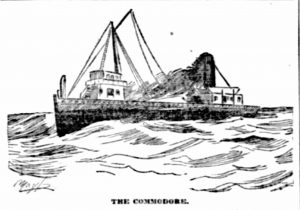

Jacksonville, Fla., Jan. 6.—It was the afternoon of New Year’s. The Commodore lay at her dock in Jacksonville, and negro stevedores proceeded steadily toward her with box after box of ammunition and bundle after bundle of rifles. Her hatch, like the mouth of a monster, engulfed them. It might have been the feeding time of some legendary creature of the sea. It was in broad daylight, and the crowd of gleeful Cubans on the pier did not forbear to sing the strange patriotic ballads of their island. Everything was perfectly open. The Commodore was cleared with a cargo of arms and ammunition for Cuba. There was none of that extreme modesty about the proceeding which had marked previous departures of the famous tug. She loaded up as placidly as if she were going to carry oranges to New York, instead of Remingtons. Down the river, furthermore, the revenue cutter Boutwell, the old isosceles triangle that protects the United States’ interest in the St. John’s, lay at anchor, with no sign of excitement aboard her. On the docks of the Commodore there were exchanges of farewells in two languages. Many of the men who were to sail upon her had many intimates in the old Southern town, and we who had left our friends in the remote North received our first touch of melancholy on witnessing these strenuous and earnest good byes. It seems, however, that there was more difficulty at the customs house. The officers of the ship and the Cuban leaders were detained there until a mournful twilight settled upon the St. John’s, and through a heavy fog the lights of Jacksonville blinked dimly. Then at last the Commodore swung clear of the dock amid a tumult of good byes. As she turned her bow toward the distant sea the Cubans ashore cheered and cheered. In response the Commodore gave three long blasts of her whistle, which, even to this time, impress me with their sadness. Somehow they sounded as wails. Then at last we began

TO FEEL LIKE FILIBUSTERS.

I don’t suppose that the most stolid brain could contrive to believe that there is not a mere trifle of danger in filibustering, and so, as we watched the lights of Jacksonville swing past us and heaved the regular thump, thump, thump of the engines, we did considerable reflecting. But I am sure that there was no hifalutin emotions visible upon any of the faces which fronted the speeding shore. In fact, from cook’s boy to captain, we were all enveloped in a gentle satisfaction and cheerfulness. But less than two miles from Jacksonville this atrocious fog caused the pilot to ram the bow of the Commodore hard upon the mud, and in this ignominious position we were compelled to stay until daybreak.

It was to all of us more than a physical calamity. We were now no longer filibusters. We were men on a ship stuck in the mud. A certain mental somersault was made once more necessary. But word had been sent in Jacksonville to the captain of the revenue cutter Boutwell, and Capt. Kilgore turned out promptly, and generously fired up his old triangle and came at full speed to our assistance. She dragged us out of the mud and we again headed for the mouth of the river. The revenue cutter pounded along a half mile astern of us to make sure that we did not take on board at that place any journeymen for the Cuban army. This was the early morning of New Year’s day, and the fine golden Southern sunlight fell full upon the river. It flashed over the ancient Boutwell until her white sides gleamed like pearl, and her rigging was spun into threads of gold.

Cheers greeted the old Commodore from passing ship and from the shore. It was a cheerful, almost merry, beginning to our voyage. At Mayport, however, we changed our river pilot for a man who could take her to open sea, and again the Commodore was beached.

The Boutwell was fussing around us in her venerable way, and upon seeing our predicament she came again to assist us, but this time, with engines reversed, the Commodore dragged herself away from the grip of the sand. And again the Commodore headed for the open sea. The captain of the revenue cutter grew curious. He hailed the Commodore:

“Are you fellows going to sea to-day?”

Capt. Murphey, of the Commodore, called back: “Yes, sir.”

And then as the whistle of the Commodore saluted him, Capt. Kilgore doffed his cap and said: “Well, gentlemen, I hope you have a pleasant cruise.” And this was our last words from shore. When the Commodore came to the enormous rollers

THAT FLEE OVER THE BAR

a certain light-headed song sprang from the throats of many of the ship’s crew. The Commodore began to turn handsprings, and by the time she had gotten fairly to sea this turned into the eye of the roaring breeze that was blowing from the southeast. There was an almost general opinion on board the vessel that life on the rolling wave was the finest thing in the world. On deck amidships lay five or six Cubans, limp, forlorn and infinitely depressed. In the bunks below lay more Cubans, also limp, forlorn and infinitely depressed. In the captain’s quarters, back of the pilot house, the Cubans’ leaders were stretched out in postures of complete contentment.

The Commodore was heavily laden, and in this strong sea she rolled like a rubber ball. She appeared to be a gallant sea boat and bravely flung off the waves that swarmed over her bow. At this time the first mate was the wheel and I remember how proud he was of the ship as she washed the white foaming waters aside and arose to the swells like a duck.

“Ain’t she a daisy,” said he. But she certainly did do a remarkable lot of pitching, and presently even some among the seamen were made ill by the long wallowing motion of the ship. A squall confronted us dead ahead, and in the impressive twilight of this New Year’s Day the Commodore steamed sturdily toward a darkened part of the horizon. The State of Florida is very large when you look at it from an airship, but it is as narrow as a sheet of paper when you look at it sideways. The past was merely a faint streak. As darkness came upon the waters, the Commodore’s wake was a broad, flaming path of blue and silver phosphorescence; and as her stout bow lunged at the great black waves, she threw flashing, roaring cascades to either side. And all that was to be heard was the rhythmical pounding of the engines.

Being an experienced filibuster, the writer had undergone a mental strain since the starting of the ship and consequently had not yet been to sleep, and so I went to the first mate’s bunk to indulge myself in all the physical delights of holding oneself in bed. The ship lurched. I expected to be fired though a bulkhead, but was not. The cook was asleep on a bench in the galley. He was of a portly and noble exterior, but by means of a checkerboard he had himself wedged on his bench in such a manner that the motion of the ship would be un-able to dislodge him. He awoke as I entered the galley, and feeling moved he delivered some dolorous sentiments. “God,” he said. In the course of his observations, “I don’t feel right about this ship somehow. It strikes me that some-thing is going to happen to us. I don’t know what it is, but the old ship is going to get it. I think.

“Well, how about the men on board of her?” said I. “Are any of us going to get out, prophet?”

“Yes,” said the cook: “sometimes

come over me, and are always right, but it seems to me somehow that you and I will both get out and meet again some-where, down at Coney Island, perhaps, or some place like that.”

Finding it impossible to sleep, I went back to the pilot house. And old seaman, named Tom Smith, from Charleston, was then at the wheel. In the darkness I could not see Tom’s face except at the times when he leaned forward to scan the compass and the dim light of the box came up on his beaten features.

“Well, Tom,” said I, “how do you like filibustering?”

He said: “I think I am about through with it. I’ve been in a number of these expeditions, and the pay is good, but I think if I ever get back safe this time I will cut it.”

I sat down on the corner of the pilot house and went almost to sleep. In the meantime the captain came on deck, and he was standing near me when the chief engineer rushed up the stairs and cried hurriedly to the captain that there was something wrong in the engine room. He and the captain departed swiftly. I was dozing there in my corner when the captain returned, and going to the door of the little room directly back of the pilot house, cried to the Cuban leader: “Say, can’t you get those fellows to work. I can’t talk their language, and I can’t get them started. Come on and get them going.”

The Cuban leader turned to me then and said: “Go help in the fireroom. They are going to bail with buckets.”

The engine room, by the way, presented a scene at this time, resembling the middle of hades.

In the first place it was insufferably warm and the lights burned faintly in a way to cause mystic and grewsome shadows. There was a quantity of soapish sea water sweeping and swishing among the machinery that roared and banged, clattered and steamed; and in the second place, it was a devil of a ways down below. Here I first came to know a certain young oiler named Billy Higgins. He was slopping around this infernal place filling buckets with water and passing them to the chainmen that wended up the ship’s side. Afterward we got orders to change our place of attack on the water and to operate through a little door on the windward side of the ship that led into the engine room. During this time there was much talk of pumps out of order and many other statements of a mechanical kind, which I did not altogether comprehend, but understood to mean that there was a general rush in the engine room. There was no particular agitation at this time, and even later

THERE WAS NEVER A PANIC

on board the Commodore. The party of men who worked with Higgins at this time were all Cubans, and we were under direction of the Cuban leaders. Presently we were ordered again to the after-hold, and there was some hesitation about going into the abominable fireroom again, but Higgins dashed down the companion-way with a bucket. The heat and hard work in the fireroom affected me, and I was obliged to come on deck again. Go-ing forward, I heard as I went, talk of manning the boats. Near the corner of the galley the mate was talking with a man.

“Why don’t you send up a rocket,” said this unknown person, and the mate re-plied: “What the h—l do we want to send up a rocket for? The ship is all right.”

Returning with a little rubber and cloth overcoat, I saw the first boat about to be lowered. A certain man was the first person in this first boat, and they were handing him in a valise about as large as a hotel. I had not entirely recovered from my astonishment and pleasure in witness-ing this noble deed, when I saw another valise go to him. This valise was not per-haps so large as a hotel, but it was a big valise anyhow. Afterward there went to him something which looked to me like an overcoat. Seeing the chief engineer leaning out of his little window, I re-marked to him: “What do you think of that blank, blank, blank?”

“Oh, he is a bird,” said the old chief.

It was now that was heard the order to get away the lifeboat, which was a mighty slippery place, and at each roll of the ship the men thought themselves likely to take headers into the deadly black sea. Higgins was on top of the deckhouse, and with the first mate and two colored stokers we wrestled with that boat, which I am willing to swear weighed as much as a Broadway cable car. She might have been spiked to the deck. We could have pushed a little brick school-house along a corduroy road as easily has we could have moved this boat. But the first mate got a tackle to her from a lee-ward davit, and on deck below the captain corralled enough men to make an impression upon the boat. We were ordered to cease hauling them, and in this lull the cook of the ship came to me and said: “What are you going to do?”

I told him of my plans, and he said: “Well, my God, who knows what I am going to do?” Now the whistle of the Commodore had been turned loose, and if there ever was a voice of despair and death it was this whistle. It had gained a new tone. It was as if its throat was already choked by the water, and this cry on the sea at night with a wind blowing the spray over the ship, and the waves roaring over the bow, and swirling while along the decks was too probably

A SONG OF MAN’S END.

It was not that the first mate showed a sign of losing his grip. At us who were trying in all stages of competence and experience to launch the life boat he raged in all the terms of fiery satire and hammer-like abuse. But the boat moved at last, and swung down toward the water. Afterward when I went aft I saw the captain standing with his arm in a sling, holding on to a stay with his one good hand and directing the launching of the boat. He gave me a five gallon jug of water to hold, and asked me what I was going to do. I told him what I thought the proper thing, and he told me then that the cook had the same idea, and ordered me to go forward and be ready to launch the ten foot dingy. I remember very well that he turned then to swear at a colored stoker who was prowl-ing around, done up in life preservers un-til he looked like a featherbed. I went forward with my five gallon jug of water, and when the captain came we launched the dingy and then he put me over the side to fend her off from the ship with an officer. They handed me down the water jug, and when the cook come into the boat we sat there in the darkness, wondering why by all our hopes of future happiness, the captain was so long coming over the side, and ordering us away from the doomed ship. The captain was waiting for the other boat to go. Finally he hailed in the darkness, “Are you all right, Mr. Grains?”

The first mate answered “All right, sir.”

“Shove off then,” cried the captain.

The captain was just about to swing over the railing when a dark form came forward and said, “Captain, I go with you?” The captain answered, “Yes, Billy, get in.” It was Billy Higgins, the oiler. Billy dropped into the boat and a moment later the captain followed, bringing with him an end of about forty yards of lead line. The other end was attached to the rail of the ship. As we swung back to leeward, the captain said, “Boys, we will stay right near the ship till she goes down.” This cheerful information, of course, filled us all with glee. The line kept us headed properly into the wind. As we rode over the monstrous roarers we saw upon each rise the swaying lights of the dying Commodore. When came the gray shade of dawn, the form of the Commodore grew slowly clear to us as our little ten-foot boat rose over each swell. She was floating with such an air of buoyancy that we laughed when we had time, and said, “What a guy it would be on those other fellows if she didn’t sink at all.” But later we saw men aboard of her, and still later they began to hall us.

I had forgotten to mention that previously we had loosened the end of the lead line and dropped further to leeward. The men on board were a mystery to us, of course, as we had seen all the boats leave the ship. We rowed back to the ship, but did not approach too near, because we were four men in a ten-foot boat and we knew that the touch of a hand on our gunwale would assuredly swamp us. The mate cried out from the ship that the third boat had foundered alongside. He cried that they had made rafts and wished us to tow them. The captain said, “All right.” Their rafts were floating astern. “Jump in,” cried the captain, but here was a singular and

MOST HARROWING HESITATION.

There were five white men and two negroes. This scene, in the gray light of morning, impressed one as would a view late some place where ghosts move slowly. These seven men in the stern of the sinking Commodore were silent. Save the words of the mate to the captain there was no talk. Here was death, but here was also a most singular and indefinable kind of fortitude. Four men, I remember, clamored over the railing and stood there watching the cold, steely sheen of the sweeping waves.

“Jump in,” cried the captain again. The old chief engineer first obeyed the order. He landed on the outside raft and the captain told him how to grip the raft, and he obeyed as promptly and as docilely as a scholar in riding school. A stoker followed him, and then the first mate threw his hands over his head and plunged into the sea. He had no life belt, and for my part, even when he did this horrible thing, I somehow felt that I could see in the expression of his hands, and in the very toss of his head, as he leaped in thus to his death that it was rage, rage, rage unspeakable that was in his hear and the time, and I saw Tom Smith, the man who was going to quit filibustering after this expedition, jump to a raft and turn his face toward us. On board the Commodore three men stood still in silence and with their faces turned toward us. One man had his arms folded and was leaning against the deckhouse. His feet were crossed, so that the toe of his left foot pointed downward. There they stood gazing at us, and neither from the dark nor from the rafts was a voice raised. Still was there this silence.

The colored stoker on the first raft threw us a line and we began to tow. Of course we perfectly understood the absolute impossibility of any such thing. Our dingy was within six inches of the water’s edge; there was an enormous sea running and I knew that under the circumstances a tugboat would have no light task in moving these rafts, but we tried and would have continued to try it indefinitely by that something critical came to pass. I was at an oar, and so faced the rafts. The cook controlled the line. Suddenly the boat began to go backward, and then we saw this negro on the first raft pulling on the line hand over hand and drawing us to him. He had turned into a demon. He was wild, wild, as a tiger. He was crouched on this raft and ready to spring. Every muscle of him seemed to be turned into an elastic spring. His eyes were almost white. His face was

THE FACE OF A LOST MAN

reaching upward, and we know that the weight of his hand on our gunwale doomed us. The cook let go of the line. We rowed around to see if we could not get a line from the chief engineer, and all this time, mind you, there were no shrieks, no groans, but silence, silence, and silence and then the Commodore sank. She lurched to windward, then swung afar back, righted and dove into the sea, and the rafts were suddenly swallowed up by the frightful maw of the ocean. Then by the men on the ten-foot dingy were words said that were still not words, something far beyond words. The lighthouse of Mosquito Inlet stuck up above the horizon like the point of a pin. We turned our dingy toward the shore.

The history of life in an open boat for thirty hours would no doubt be very instructive for the young, but none is to be told here now.

For my part, I would prefer to tell the story at once, because from it would shine the splendid manhood of Capt. Edward Murphy and of William Higgins, the oiler, but let it suffice at this time to say that when we were swamped in the surf and making the best of our way toward the shore, the captain gave orders amid the wildness of the breakers as if he had been on the quarterdeck of a battleship. John Kitchell, of Dayton, came running down the beach, and as he ran the air was filled with clothes. If he had pulled a single lever and undressed even as the fire horses harness he could not to me seem to have stripped with more speed. He dashed into the water and grabbed the cook. Then he went after the captain, but the captain sent him to me, and then it was that we saw Billy Higgins lying with his forehead on the sand that was clear of the water, and he was dead.

STEPHEN CRANE

(Copyright, 1807, by the Bacheller Syndicate.)