The past few blog posts provided a general overview of biomimicry and its founder Janine Benyus along with examples to contextualize its use in modern-day transportation, building infrastructure, and art. We learned how biomimicry has been used to improve efficiency and reduce the noise of bullet trains, inform the design of sustainable buildings that heat and cool themselves, and inspire artwork that highlights nature’s value and intellect. In this blog post, I will expand on some important biomimicry concepts as identified by the Biomimicry Institute.

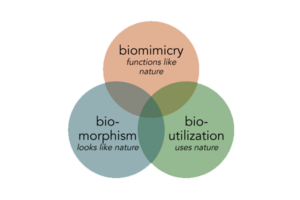

Biomimicry is just one type of “bioinspired design”, a phrase more traditionally used in engineering and design approaches. It is the umbrella category for all designs that use “biology as a resource for solutions” [1]. In addition to biomimicry, there is also

Figure 1. Three Methods of Bioinspired Design

biomorphism and bioutilitzation. Biomorphism represents design that ‘looks like’ nature. Examples of biomorphic designs include robots that look like animals, artificial plants and trees, and a building that looks like a lotus flower. Biomorphic designs can be beneficial by providing a similar positive stimulation to that of real organic structures. Having an artificial succulent on your work desk is better than no plant at all, but not as beneficial as having a real succulent with its natural air filtration properties.

Biomorphism is often confused with biomimicry, but the key difference is that biomimicry centralizes learning from nature versus solely resembling nature. Bioutilization, the third category of bioinspired design, refers to the use of biological materials or living organisms in design. Nearly everything we use and consume is derived from biological materials. In the pharmaceutical industry, for example, supplementary human insulin is most created via biosynthetic pathways in genetically engineered E coli cultures. This use of microbial cellular function to carry out complex tasks serves as a prime example of bioutilization. [2] However, it is important to note that some bioutilization processes often overlook social and environmental consequences. For example, the current method for biodiesel production in the US uses corn as a common biomass feedstock which has contributed to a shift in land use towards monoculture crop yields. This incentivized monoculture crop production takes away crop diversity, encourages the use of harmful fertilizers and chemicals that pollute the air, water, and soil, and decreases ecosystem biodiversity. [3] When adopting bioutilization methods it is vital to consider its impacts on the entire system from extraction to consumption. [1]

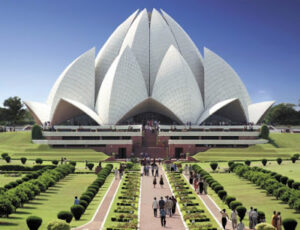

Though these various concepts are broken down into three’s, they do not need to be separate from one another. Remember the lotus building I mentioned earlier. Well, there are multiple buildings that resemble a lotus flower, but the Lotus Temple goes a step further.

Image 1. The Lotus Temple in New Delhi, India

Not only does this temple look like a lotus flower (biomorphism) but it acts like one too (biomimicry)! Located in New Delhi, India, the Lotus Temple is both a cultural and architectural masterpiece. In Hindu and Indian culture, the lotus flower often represents purity and cleanliness making its use in design symbolic [4]. The number nine, a sacred number in the Bahá’í faith, is represented in the 9-sided dome. There are 27 petals in total that make up the structure with 9 for each layer of petals: “nine entrance leaves (which mark the doorways), nine outer leaves (which form the roof space), and nine inner leaves (which enclose the central hall in an interior dome)” [5]. The Delhi climate with its varying degrees of humidity made designing to account for changing temperatures in a sustainable fashion one of the biggest challenges. Like the termite mounds example, the Lotus Temple encourages natural ventilation with openings at the top and bottom of the building. The interior dome petals are arranged in a pattern resembling the lotus flower to allow light to enter through the center skylight in an intricate and purposeful manner. Finally, the roof is equipped with solar panels, generating 20% of the temple’s electricity. [4] Like the lotus flower, the Lotus Temple embraces purity and cleanliness with a sleek design that is as efficient on the inside as it is beautiful on the outside.

References:

- “What is biomimicry” page on the Biomimicry Institute’s main website: biomimicry.org/what-is-biomimicry/

- “Cell factories for insulin production” (2014) scientific article accessed through NIH: ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4203937/

- “The causes and unintended consequences of a paradigm shift in corn production practices” (2015) article by Scott W. Fausti accessed through Science Direct: sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1462901115000908

- architecturever.com/2019/04/07/lotus-temple-new-delhi-its-bio-mimetic-history-biomimicry/

- “Explore the Lotus Temple’s Architecture Style and History” (2022) article by MasterClass staff: masterclass.com/articles/lotus-temple-design-and-history-explained