9/11 Memorial Blog

In this blog, I’ll first start with the readings about memorialization and connect them to the 9/11 memorial, and end with my own experience of the memorial and the Sound Walk.

In “The City of Collective Memory,” Boyer offers the view that “the museum offers the viewer a particular spatialization of knowledge–a storage device–that stems from the ancient art of memory” ( 380). She argues that instead of remembering with our memories, we create memorials to enhance (or replace?) our memories of an event. Through her eyes, the 9/11 memorial serves to create a lasting way to remember. But she does raise the point that “when distance appears… then history begins to be artificially recreated.” (380) Does this mean that the 9/11 memorial an artificial or accurate recreation of what happened that day? I think, because it was so carefully created and curated by such a large number of people, it represents many truths about the events of 9/11, not just the memories of one person.

Huyssen argues that modern Western culture has a preoccupation with the past and memory, and questions the necessity of memorials, saying “Is it the fear of forgetting that triggers the desire to remember, or is it the other way around?” (431) I think that we as a society are both afraid to forget the events of 9/11–so we create memorials and movies and art related to it–and also seek to honor those killed in the attacks by actively remembering them. In this way, the fear of oblivion and disappearance is counteracted with acts of public memorialization. Huyssen also brings up the point that media influences larger and larger chunks of the collective memory and global perception as time goes on. That’s especially true with the society-wide remembrance of 9/11 on that day every year. The continued media coverage, over 15 years after the event, serves to reinforce a collective memory of 9/11.

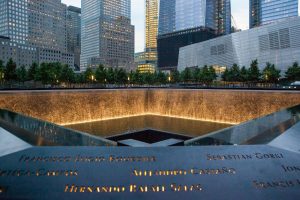

Young focuses more on actual memorials themselves, as well as countermemorials. An example of a countermemorial I thought was interesting was Hoheisel’s idea to mark destruction with destruction in the memorial to Murdered Jews of Europe (371). This idea is similar to the 9/11 memorial: the absence of an edifice where the towers once stood, an empty space. She says, “Both a monument and it’s significance are constructed in particular times and places, contingent on the political, historical, and aesthetic realities of the moment.” (373) This relates both to the countermonuments in Germany, where memorial spaces were conceived to challenge the premise of the monument. Some German artists didn’t want memorials to displace memory, so they created countermonuments, which serve as a space for memory, forcing viewers to look within themselves for memories. (373) I certainly found this to be true when I visited the 9/11 memorial. Although I only have one very vague memory of 9/11, the absence of a structure made me use my imagination and my own memory at the memorial site.

Geismar kind of argues against the memorializing process, saying that the rush to memorialization, and curation of 9/11 were rather disrespectful–a way to commodify the tragedy that occurred. Geismar brings up the presence of absence as a central theme of the memorial, which has been mediated by reproductive technologies and digital technologies that allow individual involvement in the memorial.

The Sonic Memorial really displayed the layers of New York, and presented New York as a palimpsest. Original buildings were destroyed for new buildings, which were destroyed for newer buildings, which were destroyed for monuments…etc. These historical and physical layers are represented, as Geismar says, in the Sonic Memorial through sound–mingling of voices, music, messages, and city sounds.

A quote that I particularly found to be true from Geismar was: “The fragmentary nature of the walk, coupled with the fragmentary, ever-changing nature of the site, means that the visitor is not programmed with any precise agenda, but instead feels part of a dynamic and diverse community of shared experience” (10).

As far as my experience at the memorial goes, I thought the names were extremely moving, and the whole feeling was somber and powerful. The trees around the reflecting pools, and the pools themselves in the midst of the bustling city provided an atmosphere of peace and calm. The museum itself was very informative, but I felt it was a bit morbid–this extreme obsession with collecting fragments of the destruction and people’s belongings went beyond memorialization and into curation. In the future, I believe that it will be helpful to have these pieces of history to look back on and learn from, but now, when we are still so close to the event, it feels kind of jarring.

I really, really connected with the sonic memorial. It emphasized not only the attacks of 9/11, but the whole community of New York and the collective memory of 9/11. The tape recording of the sounds when the first plane stuck were terrifying, message from hijacked plane was really hard to listen to. Both these elements in particular made 9/11 feel much more real to me, and allowed me to connect with the experience in a different way than I ever have before.

I wouldn’t say I’m a very patriotic person, but the Sonic Memorial, and being at the physical memorial stuck such a cord with me. It was extremely emotional and the audio really added to the experience of remembering and memorializing, more so than a silent memorial could.

Leave a Reply