The Captivity of the Marquis de Lafayette in Prussia and Austria, 1792-97

This exhibit follows the fortunes of the Marquis de Lafayette during the period he was held as a political prisoner in Prussia and Austria from 1792-97.

Courtesy of the Lafayette College Art Collection

Political Turmoil in France

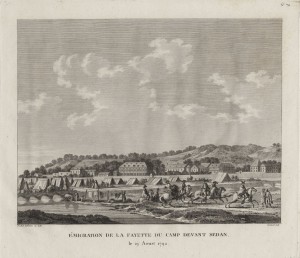

A decade after his important contribution as a nineteen-year-old Major General in the American Revolution, the Marquis de Lafayette became a pivotal player in a democratic uprising in his native France–the French Revolution. With the fall of the Bastille in July 1789, Lafayette was chosen to head the newly-formed Paris citizen’s militia. This he subsequently converted into the Paris National Guard which he commanded until October of 1791. As the Revolution gained momentum, Lafayette found it increasingly difficult to maintain order and protect the royal family. Lafayette’s affairs reached a crisis in August of 1792 after the deposition of Louis XVI, when the Legislative Assembly passed a decree of impeachment against him. At the time, Lafayette was serving with the Army on the northern French border in the newly-declared war against the Coalition (Prussia and Austria). Knowing he would face the guillotine if he remained in France, Lafayette fled on August 19, 1792 with hopes of returning to America.

Lafayette’s Capture

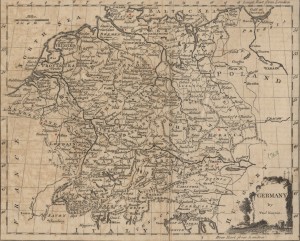

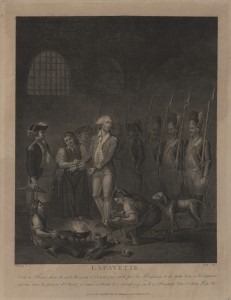

When Lafayette tried to pass through Austrian-controlled territory on his way to a Dutch port, he was quickly challenged. Although Lafayette insisted that he was no longer a French general, but an American citizen—he had been given citizenship by several states after the American Revolution—the Austrian and Prussian rulers were unsympathetic and took him captive. They were fighting their own wars against this idea of democracy of which Lafayette himself was a major proponent. Imprisoned first in a Prussian fortress at Westphalia in 1792, Lafayette was transferred several times in Prussia before his final imprisonment at Olmütz in Austria in 1794.

When Lafayette tried to pass through Austrian-controlled territory on his way to a Dutch port, he was quickly challenged. Although Lafayette insisted that he was no longer a French general, but an American citizen—he had been given citizenship by several states after the American Revolution—the Austrian and Prussian rulers were unsympathetic and took him captive. They were fighting their own wars against this idea of democracy of which Lafayette himself was a major proponent. Imprisoned first in a Prussian fortress at Westphalia in 1792, Lafayette was transferred several times in Prussia before his final imprisonment at Olmütz in Austria in 1794.

The Revolutionary Sword

One of the most remarkable artifacts associated with the Marquis de Lafayette in the College’s collection is the sword shown here. This is the sword taken from Lafayette by his Austrian captors in August, 1792. Almost all of Lafayette’s personal effects, which were confiscated by his captors, were returned upon his release in 1797, except this sword. Lafayette himself provided clues to the reason for this in a letter of 1828, describing it as having “as a pommel, a cap of liberty.” The revolutionary nature of this sword made it desirable as a trophy of war and it was eventually purchased from the Austrians by a Prussian diplomat and put on display in Berlin. In 1932, the diplomat’s family presented it to Lafayette College.

One of the most remarkable artifacts associated with the Marquis de Lafayette in the College’s collection is the sword shown here. This is the sword taken from Lafayette by his Austrian captors in August, 1792. Almost all of Lafayette’s personal effects, which were confiscated by his captors, were returned upon his release in 1797, except this sword. Lafayette himself provided clues to the reason for this in a letter of 1828, describing it as having “as a pommel, a cap of liberty.” The revolutionary nature of this sword made it desirable as a trophy of war and it was eventually purchased from the Austrians by a Prussian diplomat and put on display in Berlin. In 1932, the diplomat’s family presented it to Lafayette College.

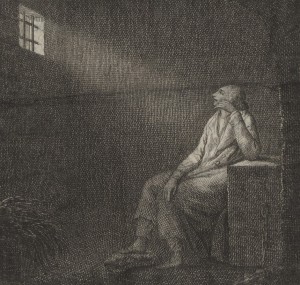

The Austrian Fortress of Olmütz

At Olmütz prison in Moravia, Lafayette was reduced to a common prisoner. His few remaining possessions were taken from him—his watch, razor, and his final books pertaining to democracy. He was unable to send or receive letters, and, by this time, his friends did not know his whereabouts. George Washington and other prominent Americans wanted to have Lafayette released as an American citizen, but America had declared her neutrality in the war between France and Austria and Prussia. They feared that America would be pulled into the French Revolution and other entanglements of politically unstable Europe.

At Olmütz prison in Moravia, Lafayette was reduced to a common prisoner. His few remaining possessions were taken from him—his watch, razor, and his final books pertaining to democracy. He was unable to send or receive letters, and, by this time, his friends did not know his whereabouts. George Washington and other prominent Americans wanted to have Lafayette released as an American citizen, but America had declared her neutrality in the war between France and Austria and Prussia. They feared that America would be pulled into the French Revolution and other entanglements of politically unstable Europe.

The Failed Escape

Word of Lafayette’s imprisonment angered Americans, who revered the boy hero of their revolution. In particular a group of Americans and others in London began to work to secure Lafayette’s release, first through diplomatic channels, then, when that did not work, by planning a rescue attempt. The group hired Erich Bollman, A German adventurer, who was able to locate Lafayette and pass him secret messages through the prison doctor. The two worked out an escape plan to be activated when Lafayette was taken for a carriage ride by his guards. The plan, unfortunately, went awry. Lafayette’s guards could not be completely overpowered, and, although Lafayette did escape on horseback, he was soon recaptured and returned to Olmütz.

Word of Lafayette’s imprisonment angered Americans, who revered the boy hero of their revolution. In particular a group of Americans and others in London began to work to secure Lafayette’s release, first through diplomatic channels, then, when that did not work, by planning a rescue attempt. The group hired Erich Bollman, A German adventurer, who was able to locate Lafayette and pass him secret messages through the prison doctor. The two worked out an escape plan to be activated when Lafayette was taken for a carriage ride by his guards. The plan, unfortunately, went awry. Lafayette’s guards could not be completely overpowered, and, although Lafayette did escape on horseback, he was soon recaptured and returned to Olmütz.

Lafayette’s Wife and Daughters Arrive at Olmütz

During Lafayette’s last two years of captivity he was joined by his wife, Adrienne, and two daughters, who chose to endure the deprivation of prison at his side. Adrienne had lost her mother, grandmother, and sister to the guillotine in 1794. She was spared only because of American diplomatic warnings to France about what the death of Madame de Lafayette would do to American public opinion.

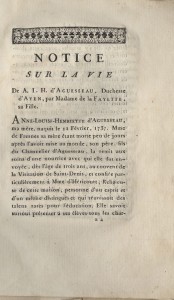

Madame de Lafayette’s Memoir

During the years that she shared her husband’s captivity in 1795-97, Madame de Lafayette secretly composed a life of her mother, the Duchess d’Ayen, a victim of the French Revolution’s guillotine in 1794. She wrote the manuscript in the margins of another volume using toothpicks and China ink. When she returned to France in 1799, she arranged for a clandestine printing of a few copies of the work on a hidden printing press in 1800. Unbound copies were distributed to family members. The Lafayette College copy of this work is one of two known copies in the United States; six copies are accounted for in France. It was a gift to the College by William and John Avery Crawford in 1990.

During the years that she shared her husband’s captivity in 1795-97, Madame de Lafayette secretly composed a life of her mother, the Duchess d’Ayen, a victim of the French Revolution’s guillotine in 1794. She wrote the manuscript in the margins of another volume using toothpicks and China ink. When she returned to France in 1799, she arranged for a clandestine printing of a few copies of the work on a hidden printing press in 1800. Unbound copies were distributed to family members. The Lafayette College copy of this work is one of two known copies in the United States; six copies are accounted for in France. It was a gift to the College by William and John Avery Crawford in 1990.

Lafayette’s Son Takes Refuge in America

Before Madame de Lafayette and her daughters went to Olmütz, she made arrangements for her son, George Washington Lafayette, to go to America where she hoped he would be taken in by his namesake, George Washington. The trip to America, though, proved to be difficult. Because the French government would not permit the trip, all the arrangements had to be made in secret. Madame de Lafayette enlisted the aid of James Monroe, who secured an American passport and George set sail on April 20, 1795. Because of America’s position of neutrality toward France and her enemies, Washington then in his final years as president, was placed in an awkward position with regard to George Washington Lafayette’s presence in America. At first, he arranged for the youth to live in New York under the oversight of Alexander Hamilton, but eventually brought him to live at the president’s house in Philadelphia.

de Lafayette and her daughters went to Olmütz, she made arrangements for her son, George Washington Lafayette, to go to America where she hoped he would be taken in by his namesake, George Washington. The trip to America, though, proved to be difficult. Because the French government would not permit the trip, all the arrangements had to be made in secret. Madame de Lafayette enlisted the aid of James Monroe, who secured an American passport and George set sail on April 20, 1795. Because of America’s position of neutrality toward France and her enemies, Washington then in his final years as president, was placed in an awkward position with regard to George Washington Lafayette’s presence in America. At first, he arranged for the youth to live in New York under the oversight of Alexander Hamilton, but eventually brought him to live at the president’s house in Philadelphia.

This letter, at left, w as written to Washington by his namesake after the president’s retirement to Mount Vernon, only days before word was received of the Lafayette family’s release from prison. In fact, in the letter young George speaks of an attempt to get news of his family: “We have seen at Alexandria the captain of the ship Saratoga, who could not give us any information concerning my father and family.” By October, George was on his way back to Europe to be reunited with his family, carrying with him a letter from Washington to Lafayette, which began: “This letter will, I hope and expect to be presented to you by your Son, who is highly deserving of such Parents as you and your amiable Lady…His conduct, since he first set his feet on American ground, has been exemplary in every point of view.”

as written to Washington by his namesake after the president’s retirement to Mount Vernon, only days before word was received of the Lafayette family’s release from prison. In fact, in the letter young George speaks of an attempt to get news of his family: “We have seen at Alexandria the captain of the ship Saratoga, who could not give us any information concerning my father and family.” By October, George was on his way back to Europe to be reunited with his family, carrying with him a letter from Washington to Lafayette, which began: “This letter will, I hope and expect to be presented to you by your Son, who is highly deserving of such Parents as you and your amiable Lady…His conduct, since he first set his feet on American ground, has been exemplary in every point of view.”

Lafayette’s Release from Olmütz

When Napoleon Bonaparte and his revolutionary armies had conquered Austria in 1797, a clause was added to the Treaty of Campo Formio for the release of Lafayette. John Parish, an American diplomat in Hamburg, was Lafayette’s host the night of his release on September 19, 1797. After two subsequent years in exile in Holland, Lafayette was finally able to return to France in 1799.

When Napoleon Bonaparte and his revolutionary armies had conquered Austria in 1797, a clause was added to the Treaty of Campo Formio for the release of Lafayette. John Parish, an American diplomat in Hamburg, was Lafayette’s host the night of his release on September 19, 1797. After two subsequent years in exile in Holland, Lafayette was finally able to return to France in 1799.

All images, except the title painting, are from the Marquis de Lafayette Collections, Skillman Library, Lafayette College.

Exhibit curated by Emelie George ’02. Redesigned by Alena Principato ’15.