Alena Principato ’15 discusses her Visual Resources Internship with DSS cataloging images from the Experimental Printmaking Institute

This summer I completed an internship under the guidance of Kelly Smith, Lafayette College’s Visual Resources Librarian. I have been learning about visual resources management and assisting Kelly with the digitization of the Experimental Printmaking Institute’s body of work. Each print that is digitized must be photographed, edited, and uploaded to Shared Shelf, a cloud-based cataloging and content management system developed by ARTstor.

What is cataloging and how does it work?

According to Cataloging Cultural Objects: A Guide to Describing Cultural Works and Their Images, “to catalog a work is to describe what it is, who made it, where it was made, how it was made, the materials of which it was made, and what it is about.” This information is also referred to as metadata (essentially, “data about data”), especially when it is entered in a digital format.

Recording such data may seem straightforward, and often is; the name of the artist, the measurements of a work, and the date of creation are simple enough to ascertain. However, selecting the subject of the work is more ambiguous. As Shared Shelf explains, the subject field contains “terms that identify, describe, and/or interpret what is depicted in and by a work.”

Consider what it means to “interpret”—when a person views an art object, they draw conclusions about what it means, often through the lens of their unique background and personal experiences. A detail in a painting that captivates one person may be completely overlooked by another.

The challenge for a cataloger of a visual work is to consider all of these potential viewpoints. The cataloger must be observant and sort out what information about a work is relevant to include, and what elements are trivial or unnecessary to describe. It’s helpful to think of subject terms as the keywords used to conduct an image search. Catalogers have to anticipate future users’ research needs—which could be on a general subject or specific topic—and account for both when they are describing a work.

While there is no one standard governing the selection of subject tags, catalogers may choose subject terms from lists of pre-set subject identifiers known as controlled vocabularies. For cataloging the Experimental Printmaking Institute’s works, we selected four resources for subject terms: Getty’s Thesaurus of Geographic Names (TGN) and Art & Architecture Thesaurus (AAT), Iconclass, and Library of Congress Subject Headings. Each helps standardize the cataloging of visual resources by providing a controlled vocabulary to minimize variations in cataloging by different institutions.

My process for subject tagging the EPI works begins with identifying general terms and narrowing down from there. First I evaluate the work for major concepts and overall themes. Once those are established, I take a closer look at details in the image that seem important, such as an identifiable person, place, or event. Details do not necessarily have to be a focus of the work as a whole to merit being included–if a tag could be useful in helping someone locate an image of a particular subject, it may be worth including. However, it’s not a good idea to tag details that are truly a minor or irrelevant part of the image, since this could result in overemphasizing their importance.

An Example

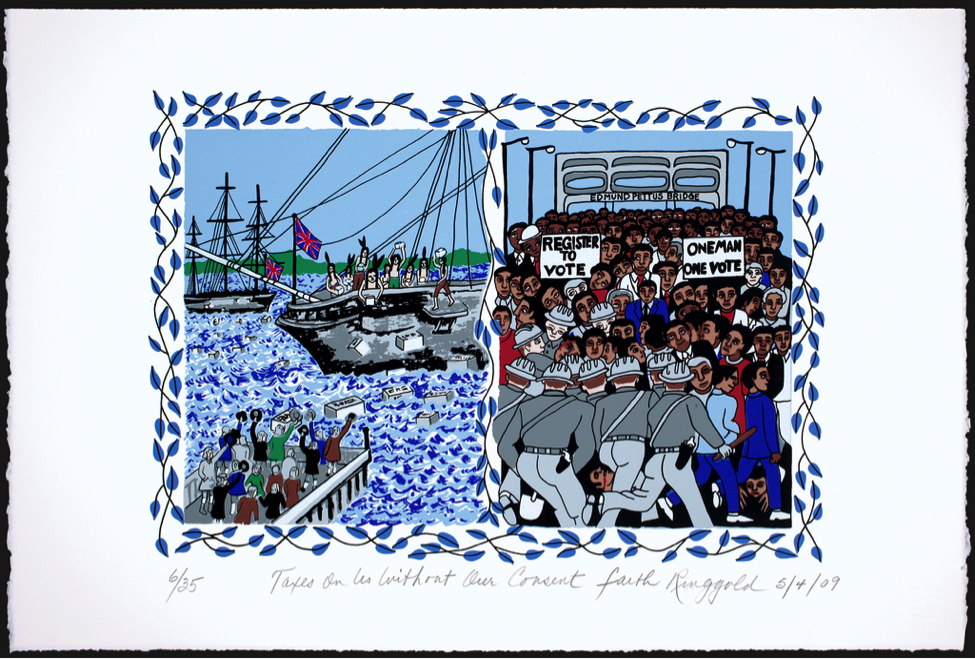

Here’s how I approached cataloging “Taxes on Us Without Our Consent,” a screen print by Faith Ringgold.

Step 1: Assess the overall work and determine key themes.

“Taxes on Us Without Our Consent” is part of a portfolio of prints by Ringgold called Declaration of Freedom and Independence. The illustrations juxtapose famous scenes in early American history with events from the Civil Rights Movement, creating an interesting commentary on the principle of freedom in American history. Each print is based on a quote from the Declaration of Independence. I used the subject terms “United States, Declaration of Independence” and “Freedom” to describe the general themes of the work. Since the title and subject matter of the work are based on the section of the Declaration discussing taxation without representation, I also tagged it with “Taxation.”

Step 2: Identify specific, important details.

Drawing on my knowledge of American history, I immediately identified the image on the left as a scene of the Boston Tea Party, in which colonists protested unfair taxes on imported British goods by dumping chests of tea into the Boston Harbor. A search in the Library of Congress Subject Headings database gave me the term “Boston Tea Party, Boston, Mass., 1773.”

Step 3: Use textual clues to dig deeper.

Part of the image depicts a group of African American protesters in what appears to be a demonstration on voting rights. I noticed that the bridge in the background is labeled, so I searched online for “Edmund Pettus Bridge” and discovered that the event depicted is the 1965 Selma-to-Montgomery March for voting rights. Despite this detective work, it turned out there wasn’t a subject heading for the event in the LOC database, so I chose a more general term “Suffrage.”

Step 4: Search for outside resources.

Sometimes searching online for the title of a work can yield helpful results. Artists’ websites along with museum and gallery sites may provide additional information about a work.

A final note of caution when choosing subject headings: It’s best to identify the subject of a work as fully as possible, but it’s better to be cautious rather than make assumptions. If you mislabel the subject of a work, people may misinterpret it, compromising the artist’s vision for the work. Sometimes you may only be able to label the literal elements of the image. If you have a guess about the specific subject, either find a way to confirm it or leave it out.

What I Learned

Cataloging is very detail-oriented work with a lot of rules attached. Yet, ambiguity exists within the cataloging realm, especially when it comes to subject tagging, since catalogers must make important decisions about how to describe a work in a way that will allow others to access it in the future. Through my internship I’ve discovered that cataloging is not purely a science—it’s an art.